Covid in Norway: 'Flurona' is Here--a new risk assessment spells out the state of affairs: vaxx failure, odd seasons, and the lingering question of VAIDS

Bonus features incl. lots of data, charts, and figures--as well as dark musings about a future in which 90+ percent of all Norwegians are at-risk due to the potential of VAIDS

After yesterday’s rather long post, I shall try to keep this one shorter. The topic is—the Institute of Health’s (IPH) most recent Assessment Report, dated 31 March 2022.

Already in the last couple of weekly updates, the IPH looked at any number of ‘other respiratory viruses’, and now we’ve finally made it through the looking glass, as this report is now entitled ‘Risk of the Covid-19 and Influenza Epidemics in Norway’.

In other words: welcome to ‘Flurona’ season (which I wrote about back in early Feb. 2022).

Executive Summary (pp. 4-5)

Written at the end of the Omicron (BA.2) wave, the situation continues to be ‘dynamic’, and the epidemic shall further be monitored, the report maintains. There’s no real difference between Norway and the other European countries, at least in terms of epidemiological pressures etc., but a ‘new wave of Covid-19, most likely [next] autumn or winter, or a new wave with a new variant already before that’ is expected. Furthermore, the IPH thinks ‘that it is also possible that the epidemic will continue on a medium-low level throughout the summer’.

Yet, I’d move that the money paragraph is the next one:

This season’s influenza outbreak is currently unfolding…the number of new hospitalisations with influenza per week has been rising fast, from 9-13 admissions in weeks 1-7 to 136 in week 12. The numbers for week 12 are expected to be adjusted upwards. So far, there were 409 admissions, of which 10 patients ended up in the ICU because of influenza, which was found in 11.1% of all analysed samples in week 12. The epidemic affects especially minors and young adults.

The main variant of this season’s outbreak is influenza A (H3N2), an offshoot of the Bangladesh variant. Luckily, at least for Norway, the influenza A (H3N2) virus was circulating earlier, and, according to the assessment, ‘was the basis for this season’s vaccine’.

As regards Norway’s neighbours, mention is made of Denmark, which is ‘currently experiencing a large influenza epidemic’: there were 12 admissions in week 6, and there’s 631 in week 12.

Risk Assessment for Covid-19

Apart from the ‘known unknowns’ mentioned above, it is interesting to note that the IPH now credits ‘population immunity’ (befolkningsimmunitet) and ‘seasonal effects’ (sesongeffekt) for the ebbing of the winter wave.

It is expected that new admissions will continue to decline to ‘as low as under 100 per week’. Thus, the pressures resting on society are receding, which translates into less and less risk for any individual to get infected (again, I suppose).

The IPH concludes its Covid-associated section with calls to further surveillance due to the ‘unknown unknowns’ of, well, the future.

Risk Assessment for Influenza

It is expected that influenza will spread in April, driven in part by the Easter break (which is kinda like Thanksgiving in the US in terms of travel and reunions) and seasonal effects.

The most problematic issue may be that due to the absence of influenza in the past two seasons, few Norwegians may have had prior experience, i.e., their immune systems aren’t ‘trained’, and everyone should get ready.

Getting Ready as Society

This section includes the usual ‘let’s strengthen surveillance mechanisms’ yada-yada, with perhaps the below two issues deserving of attention:

As it looks right now, society can continue with normal everyday life without significant anti-Covid measures. Groups with elevated risks for a severe disease shall obtain access to vaccines, antiviral treatments, and appropriate advice to reduce infection risks. The IPH continuously assesses vaccine offers and may recommend the use of new variant vaccines.

The situation continues to be hard to predict…any change in assessment may be due to, e.g., the appearance of a new virus variant or a reduced effect of vaccination, or perhaps these two in combination.

The population must be prepared for a stronger return of the epidemic and should be prepared appropriately.

Handling of Influenza

Same as above, but there are also two paragraphs on vaccines and treatments:

Vaccination against influenza continues to be recommended for those at risk, but it offers little protection against infection among seniors. There is similarly some protection

against infection and limited protectionagainst severe disease [corrections on 1 March 2022].In-time antiviral treatment, especially for those at risk and with severe disease to prevent outbreaks in vulnerable settings.

Noteworthy Issues #1: Covid-19

There are some issues I’d like to highlight, in particular the below fig. 1 (p. 7), but note the sentence above the figure: ‘the number of hospital and ICU admissions, as well as deaths, increased markedly during the Omicron winter wave’:

Two things to note here: first, in Norway, the delay between onset and peak of both ‘hospitalisations’ (innleggelser, the blue line) and ‘deaths’ (dødsfall, the grey dotted line) isn’t 2-4 weeks—it’s 8-9 weeks. Hence, if the epidemiological situation in your region is about to peak in terms of the former, Norway tells you what to expect some two months later.

Second, note that Omicron’s grim harvest appears mainly due to the sheer numbers of infected, which explains why ‘ICU admissions’ (nye på intensiv, the green line) isn’t worse than, say, in spring 2020.

Also, the median age of Covid-associated deaths was 84 (average: 82). ‘In the past three weeks [8-29 March, or something like it], a quarter of all deaths was over 91, a quarter between 86-91, another quarter between 76-86, and the remaining quarter under 76.’

Still, there continues to be uncertainty as to the share of the population that has been infected, with approx. 70% of respondents in a recent survey (Symptometer) telling the Health Directorate that they had tested positive (p. 7).

Even though we don’t know much about these—dare we say ‘crucial’?—issues, the assessment simply holds that ‘the Health Directorate has discontinued the collection of data’ pertaining to hospitalisation, ICU admission, and ventilation requirements ‘as of 22 March 2022’ (p. 8). In other words: we’re flying blind with respect to Covid-19 now.

Sidenote: I’m unsure what to make of this: it’s not that we’ve done such a grand job in the past two years, perhaps this is a change for the better? On the other hand, given the awful numbers of ‘incidental Covid’ (i.e., admission for something other than Covid-19, but with a positive PCR test), the authorities may have ulterior motives here…

Before we move on to influenza, one last word about pressures on the healthcare sector: almost half (44%) of all municipalities reported ‘challenges’ with respect to healthcare workers; four out of ten (39%) of municipalities cited ‘challenged’ capacities (hospitals, care homes); and six out of ten (62%) GPs and family doctors—Norway’s front-line healthcare professionals—similarly reported challenges (pp. 7-8).

Noteworthy Issues #2: Influenza

As summarised visually in Fig. 4 (p. 8), it’s now a strangely late influenza outbreak going on that looks as it’s on an exponential upwards trajectory.

The main strain is influenza A (H3N2), very much related to South-East Asian variants; the virus is classified as A/Bangladesh/4005/2020-like virus (genetic group: C.2a1b.2a.2).

We further note the abysmally small sample size: 47 samples were sequenced in week 12, of which 22 returned influenza A, four RSV, and five Sars-Cov-2 (p. 9).

Noteworthy Issues #3: Flurona

So far in this season, 238 patients were confirmed both Covid-19 and influenza, 74 of whom in week 12. Most of them were between ages 10-30. It is not unexpected to detect co-infections when two respiratory viruses are circulating at the same time and infection pressures are high, but the overall number is expected to be small. The disease picture can become more serious with such a co-infection, but it is uncertain whether this applies also to the younger age brackets.

So far, influenza-associated pressure on the healthcare system is manageable, albeit rising. This influenza season there were a total of 409 admissions (J09-J11), of whom 39 occurred in the past two weeks. There is an expectation that these numbers will be adjusted upwards as more reports are coming in.

Noteworthy Issues #4: Modelling vs. Reality

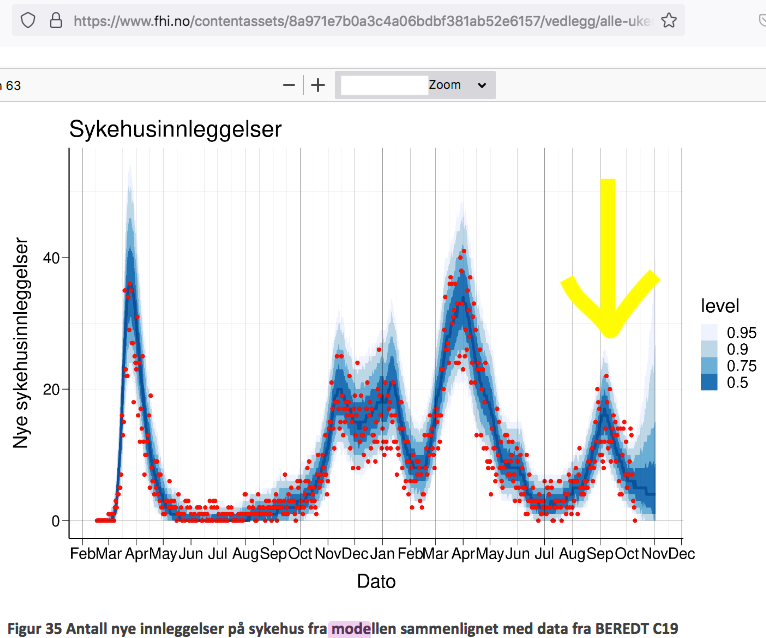

Norway’s authorities use two models, and Fig. 6 (p. 10) shows the mathematical model:

Note the following issues: (1) is the Delta wave; (2) is the Delta-Omicron transition around Christmas; and (3) is the Omicron wave.

While the modelling appears to conform quite well to what happened, it’s worth pointing out that the scale is extremely different; for comparison, here’s the IPH’s fig. 35 from week 40 (p. 51, 4-10 Oct. 2021), which corresponds to the ‘bump’ marked (1) in the above chart:

Noteworthy Issues #5: RSV Infections

As per Fig. 10 (p. 12), reproduced below, the late influenza outbreak isn’t the only oddity: there was also an ‘unexpectedly early’ outbreak of RSV this winter.

The remainder of the assessment contains various comparisons to other countries (pp. 13-16), but note that they’re all based on OWID or other public health authorities (hence I won’t discuss them in detail here).

Evolution of Sars-Cov-2 (pp. 17-18)

Little new stuff here, with the IPH expressing its main concern almost as an afterthought:

In the main, it’s the spike protein that defines antigenicity of Sars-Cov-2. Whether a recombinant [variant] is well recognised by one’s immune system largely depends on the location of spike and any changes in this protein…

In Norway, we also observe the emergence of BA.2 with an additional mutation (K356R) in the important receptor binding domain in the spike protein. It is still too early to determine whether this provides an advantage with respect to infection. We do not now see any new variants that in Norway will have greater transmissibility than Omicron BA.2.

Yet, the oddest part to me is this (my emphasis):

We have no reason to fear that the vaccines will be less effective against recombinant viruses we know today…the vaccines have so far proved to protect very well against serious disease regardless of variant and against the original virus. In addition, many in Norway have now further strengthened their immunity through infection.

Ahem. I call BS on that one (see here for a current summary, i.e., yesterday’s post). I particularly don’t see, logically speaking, how these sentences can both be true at the same time: the ‘vaccines’ were supposed to prevent transmission and infection, but apparently, overcoming an infection despite the high level of injection uptake is somehow ‘further strengthening’ one’s immunity.

Perhaps the IPH would like to explain this in terms that aren’t illogical and contradictory?

Oh, wait, there’s an entire section on ‘immunity’ (pp. 18-19, my emphases)

Immunity can come from vaccination, infection, and the combination of these (hybrid immunity). We expect that the population now has widespread immunity to SARS-CoV-2, and this provides good protection against serious illness. This has been of great importance because the winter wave with the omicron variant has given little serious illness and hospitalisations.

This paragraph shows the absurd clueless- and helplessness of the IPH: they ‘expect’ things, because the Omicron wave hasn’t caused much trouble. Ahem. As above, I’d call BS on that one, for the numbers since, say, the Delta wave in September 2021 are telling: most of epidemiological pressure emanates from ‘the vaccinated’, in particular the ‘boosted’, as we’ve discussed weeks ago.

(Really, I’m a humanities scholar, and this is patently absurd from a purely discursive point of view, but in real-world terms, it’s almost painful to read it once the implications are considered.)

Population immunity will be even greater after the winter wave when a large proportion of the population has undergone infection with the Omicron variant.

To me, this reads like: now that we’ve kinda cobbled together our own definition of ‘immunity’, why bother with differentiations between, say, humoral and cellular kinds of immunity? Still, the most striking inanity is that—even if we take the IPH’s odd definition in the preceding paragraph, I think it’s fair to state that there’s differences between immunity ‘from vaccination, infection, and the combination of these’. Clearly, an overcome infection (‘natural immunity’) appears to be ‘better’ than its ‘vaccine-induced’ companion, in particular once you consider that the latter apparently didn’t really work.

The immune response to Sars-Cov-2 is complex and consists of many different mechanisms that have a protective effect in different ways. Simply put, neutralising antibodies protect against the establishment of the infection in the body, while cellular immune responses (T cells) mainly protect against serious illness and death after an infection has been established.

This means that even if antibody levels are gradually reduced to below a level that protects against infection, protection against serious illness and death will remain present as long as cellular responses are maintained, and the immune system is ready to mobilise antibodies (from memory B cells) quickly and powerfully.

See what they are doing here? They are telling you that it’s ‘normal’, or natural, that antibody levels wane over time. So, nothing to see here, ain’t it?

The time course of the deterioration of immunity and reduced protection after vaccination may be affected by conditions such as age, immune status, and general state of health. We must expect deterioration of protection over time. It is not well enough known how the number of vaccine doses and the number of infections with different virus variants, as well as the time intervals between events, affect how well immunity is preserved. Protection against infection and transmission deteriorates faster than protection against serious illness. This can largely be explained by the fact that neutralising antibodies naturally decrease faster, while the cellular immune system persists considerably longer.

And here’s the admission that they don’t know enough (much) about what’s going to happen. I’m glad we’ve ditched the data collection and publication to actually continue to figure this one out in a transparent, scientific way.

Also, I’d have a follow-up question concerning cellular immunity: will one’s innate immune system continue to work after repeat injections with experimental biologicals (gene therapeutics)?

You’d think that this question would have crossed anyone’s mind over at the IPH, but no, you’re on your own on this one, I suppose, as the final paragraph I’ll cite here shows:

Vaccine-induced protection against serious illness in the general population is high shortly after a booster injection. Duration of protection is not established due to the short follow-up time. This protection decreases minimally in the first 2-3 months after the booster injection, including among the elderly over the age of 65, cf. Figure 16 [see below]. Combination of vaccination and Sars-Cov-2 infection provides high protection against serious illness in the general population. So far, there are no definite signs of impaired protection against serious illness among people with vaccination with three doses, regardless of age group.

And here’s the sad and sorry truth: this is an admission of ‘vaccine failure’ as the IPH spells out that ‘vaccination’ alone doesn’t protect you. They also don’t know anything about how long you’ll be protected because there’s no data, to say nothing about the little fact that nowhere in the EUA applications did the manufacturers—or the regulators, for that matter—actually assess repeat injections with these products.

Yet, the most serious problem rests with the lie-by-omission in the final sentence:

So far, there are no definite signs of impaired protection against serious illness among people with vaccination with three doses, regardless of age group.

What’s the omission, you ask? Well, there’s no mention of the degrading of one’s natural immune system after repeat mRNA injections, i.e., VAIDS.

Darkening Thoughts

We don’t know much about this—Igor Chudov and Geert Vanden Bossche are on top of this issue—but to me, given the ‘untimely early’ RSV wave in autumn and the equally ‘untimely late’ influenza outbreak right now, I’d really like to know, to say nothing about the absurd ratio of hospital admissions: 1 (Covid-19 as main cause) vs. 13 ‘incidental’ Covid admissions discussed in yesterday’s post.

At this point, I think everyone should start to worry, as Norway has begun to offer a fourth injection to certain people. Here’s Fig. 18 (p. 47 from the update for week 12) that shows injection uptake by age cohorts:

If you’re interested in geographical dispositions, go to Fig. 19 (p. 48, ibid.), which shows uptake across Norway’s provinces (fylke), which hovers between 90-93% of the ‘eligible’ population.

Concluding (Dark) Musings

I’ll conclude with the below fig. 16 (p. 19, from the Risk Assessment), which shows how ‘well’ the injections actually ‘work’, if that’s the proper word to use here:

See if you can spot any meaningful difference in incidences of hospitalisations and death with Covid-19 for ages 18-64 (7 Jan.-27 March 2022).

Why did we as a society actually take the unprecedented risk of repeat injections? I mean, for that ‘difference’?

As a concluding (very dark) sidenote, do think about the fact that approx. 500 years ago, Scandinavia’s population was about 1/10 of what it is today.

Now, if many, if not most, injected people will die well before they’d do without these products in their system, are we moving back to the late medieval/early modern population numbers?

Even if this will play out over a couple of decades, there’s no way any society will be able to keep all the infrastructure up and running, in particular outside urban centres.

I suspect live will change drastically over the coming years and decades.

Let’s all try to at least become emotionally, mentally, and psychologically prepared.

Just a few thoughts. RSV was not around in adults when I worked in healthcare x 40 years. It did appear on the scene in kiddies in the 80’s? Why is it now in adults?

H3N2? In the past, this strain causes more hospitalisations. Birds being culled by the millions now in USA. Different strain. Finally nearly every last person we know here in Devon, England has covid. Cold like symptoms. Has the covid virus become less virulent? Seems like it. But the vaxxes appear to be totally useless. Every older person we know has had three jabs and seem desperate for their fourth. They do not see what is in front of them.

One last thought tamiflu, an antiviral costs about $90 in the USA and is completely useless. We still don’t have access to ivermectin for early treatment for covid in the UK. Why did all countries, USA, UK, Norway STOP counting cases practically on the same day.

I can see chaos is rampant, record breaking cases of the plandemic, crisis in Ukraine/Russia, threat of “war”, airports cancelling flights in UK and USA due to ? because this appears to be all part of a sinister plan to create chaos and continue it until everyone folds. Maybe not, but it sure feels that way💕💕

Rough translation from Folkhälsomyndigheten, since they can't be arsed to provide information in english:

During week 11, 94 cases of flu verified by lab testing (whereof 91 type A and 3 type B). In comparison, week 10 saw 44 cases reported, of which 43 type A and one type B. The majority of cases come from Götaland (54%) and Svealand (37%). My note: -land denotes region, and these two regions are the most populous, so no surprises there.

Of subtyped samples so far during this season, 99% are flu A(H3N2).

During weeks 10 and 11 close to 10 000 and 9 000 samples resp. were analysed for flu. Of these, 0.5% and 1% resp. tested positive for flu.

The following links to the weekly update, which has self-evident graphs and charts halfway down the page:

[https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/folkhalsorapportering-statistik/statistik-a-o/sjukdomsstatistik/influensa-veckorapporter/aktuell-influensarapport/]

This should work as a like-for-like comparison seeing how similar Sweden and Norway is. When the flu was especially bad, 2017-2018, as much as 10% of ICU beds were filled (60 out of 600, yes we really only have 600 ICU beds for a population of 11 000 000 with the EU's most expensive and least available/efficient healthcare system, counted as money/cap).

As for demographics - comapare african wild dogs, hyenas and lions. Let's say each group loses 50% of its members. For the wild dogs it would take maybe ten years to bounce back if its a one-off thing. Prolific, every female bears litters, and great pack hunters where everyone cares for everyone's pups. For the hyenas it would take longer due to their smaller litters, and their pack structure being less mutually supportive, so let's say twenty years just to make a figure up from nothing. For the lions it means extinction, as they will never be able to make up the numbers, facing competition from wild dogs and hyenas in every niche, and having mating and cub rearing social patterns which keep the number of offspring limited.

Now look at the islamic world, Africa, the Subcontinent and China. If their populations were halved, they could if they wanted to be up to todays numbers inside 20 years. For north/south americans and europeans, it could very well mean extinction.