With No Cost/Benefit Analysis Done, Questions About the Price Tag of 'Addressing Climate Change' Emerge

Guess what, according to Øystein Sjølie, costs may be as high as US$ 50-60b annually for Norway's 5.6m residents: multiply by the relevant factor for your place of residence

It now seems that we’re soon facing the greatest reality-check of all time: admission by one or the other gov’t (agency) about the true costs/benefits of doing something™ about Climate Change™.

These days, with the electoral campaign picking up speed in Norway, new estimates are surfacing, which are very well worth your attention. Especially as the gov’t has been forced to admit it spent tons of money without any data or tangible results to show for:

So, down that rabbit-hole we venture once more.

Translation, emphases, and [snark] mine.

Will the Climate Target Cost Norway 500 Billion NOK a Year [ca. US$ 50b]?

The Ministry of Climate and Environment will not publish any estimate for the costs of the climate target that has been adopted. Then we will have to do the math ourselves, writes economist Øystein Sjølie.

An op-ed by Øystein Sjølie, via Finansavisen.no, 6 Aug. 2025 [source; archived]

In June, the Storting adopted a new climate target: Norwegian emissions shall be 70 per cent lower in 2035 than they were in 1990. Norway has been pursuing climate policy since 1990. Emissions are still only 12 per cent lower, despite a number of measures [what a policy, or set (cacophony) of policies is that? It’s been 35 years, and something™, very clearly so, hasn’t been working]. The best known and most expensive is the electric car policy, which costs the state 50 billion crowns a year [as the above piece indicates, it’s rather 60+ billion per year, but at that price tag, whatever]. So how much will it cost to cut emissions by 70 per cent? The bill does not answer that, at least not in an understandable way.

There are zero-emission societies in the world, but these are without exception extremely poor

In several postings, including in Finansavisen, I have called for estimates. Climate and Environment Minister Andreas Bjelland Eriksen (Ap [i.e., Labour Party currently running the gov’t]) has told me three times on social media that the ministry has made estimates of the costs. However, he does not say what the estimates are. When I asked his own communications department, I received a quick answer:

The socio-economic costs of the emission reductions that are the basis for the projections or for the climate plan as a whole have not been calculated.

How High Could the Costs Be?

In 1990, Norwegian emissions were 50 million tons. A cut of 70 per cent corresponds to 35 million tons. The Ministry of Finance estimates that the quota price will be around NOK 1,000 [c. US$ 90-100] per ton in the coming years. In this case, this means that climate policy will cost NOK 35 billion per year [c. US$ 350m]. This is the absolute minimum. Half of Norwegian emissions are subject to the quota system. To illustrate the cost of high climate targets, I will nevertheless ignore quotas in the following [forget about all of this; Norway has 5.6m inhabitants—just multiply by the respective factor in regards to population of (insert your place of residence) to arrive at a very rough, back-of-the-envelope calculation of what the cost would be; I’ll start: Austria has 9.2m inhabitants, which is approx. 64% higher than Norway’s—we’ll clock in at a value that would be around US$ 570-600m per year].

Most measures cost significantly more than NOK 1,000 per ton. The CO2 tax in Norway is 1,200 kroner per ton, and is set to increase to 2,400 kroner in 2030 [a doubling in five years, which corresponds to compound annual tax increases in excess of 14%]. This will trigger physical measures, such as replacing a gasoline-powered machine with an electric machine, which costs up to 2,400 kroner per ton of emissions saved [will that machine’s acquisition be factored into by way of cradle-to-grave? In addition, that kind of massive tax hike will likely also trigger something else, such as an economic crisis] .

The CO2 tax is just one of many political measures. The Norwegian Public Roads Administration [Statens vegvesen] has recently cut its emissions from asphalt paving, including by replacing petroleum with vegetable oil [if that works, I’d be technically fine with this as no-one should eat seed oils in the first place; fun fact: if you go to Norwegian supermarkets, there’s a ton of seed oils on sale at discount prices while extra virgin olive oil from the Mediterranean sells at premium prices]. The Norwegian Public Roads Administration has imposed a ‘tax’ of NOK 7,500 per tonne of CO2 on its purchases [on itself (!); in my line of work, academia™ (sic), when I get some grant money for publications, the granting institution must pay the gov’t VAT to the tune of 25%; universities in Norway arte public institutions funded by the gov’t, and, yes, this all flows into GDP calculations™].

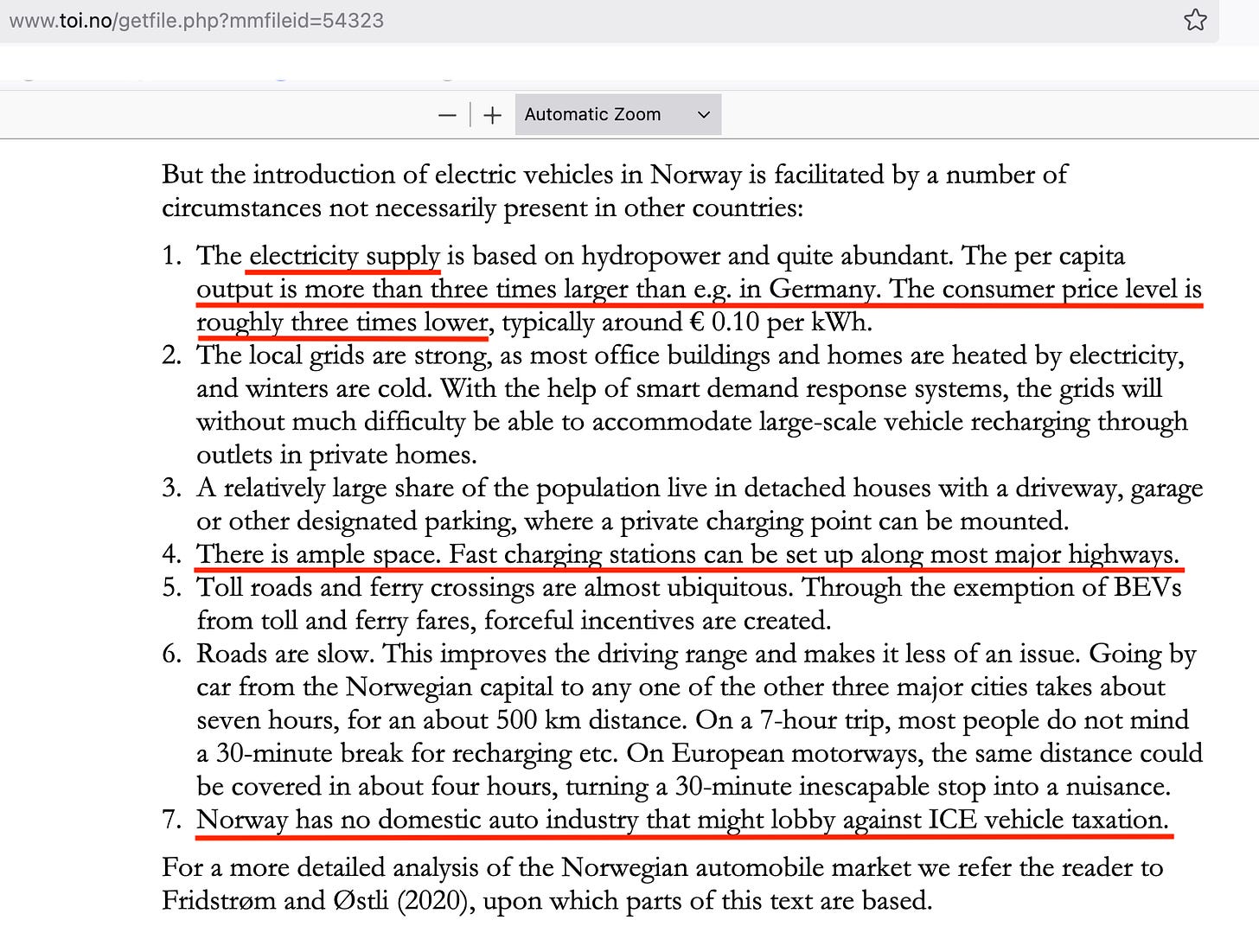

The Institute of Transport Economics [Transportøkonomisk institutt] has calculated that the climate cuts [sic] from the electric car policy cost from NOK 5,000 per tonne for vans to NOK 12,000 per tonne for passenger cars. After the partial introduction of VAT on electric cars, the cost is somewhat lower, but still high.1

The electric car policy and biogenic oil count positively in the Norwegian climate accounts, but both result in ‘carbon leakage’. Producing electric cars is more energy-intensive than fossil cars, and part of the power in the Norwegian power system is coal-fired. We import over 90 per cent of the raw materials for biofuels, and there are large emissions in their production.

To the extent that the bill has a cost estimate, it is that the ‘marginal costs’ of a 70–75 per cent cut will be NOK 6,300–8,350 per tonne. If the average cost of measures in Norway is NOK 5,000 per tonne, which may be in line with this, the total cost to society will be NOK 165 billion per year [that sounds like a lot, but consider the following: the current (2025) price per tonne of CO2 emissions is 1,250 NOK; the costs per tonne for 70-75% cut are higher by a factor of 5 (for the lower end of the estimate) and a factor of 6.7 (for the higher end of the estimate); if CO2 taxes are to double in the next five years, where do you think these will go beyond 2030?]

A cost of NOK 5,000 per tonne on average for such large cuts seems modest, considering that we already have measures that are significantly more expensive than this [maybe, maybe not—but give the above-related built-in tax hikes beyond 2030 a thought: I respectfully disagree with that bit of lipstick on the pig, mainly because these costs will be borne by John & Jane Q. Public].

Energy analyst Vaclav Smil has estimated that the costs of reaching net zero in 2050 are at least 20–25 percent of GDP in rich countries.2 In Norway’s case, this means costs in the region of NOK 500 billion for a 70 per cent cut. For comparison: total health expenditure in Norway is around this, of which one third is made up of hospitals [that’s a stupid comparison, I’d argue, for healthcare spending is the functional equivalent of sustained spending on a rapidly depreciating asset, which I think has little place in GDP or the like; another aspect to consider is the fact that with the wave of boomers retiring now, spending requirements in the healthcare sector will increase].

Can it really be that expensive to cut emissions? That it is extremely expensive seems likely. The connection between prosperity and energy is close, for good reasons. And in the world, 80 per cent of the energy is still fossil. There are zero-emission societies in the world, but these are without exception very poor.

Therefore, we are still calling for the Minister of Climate Change’s estimate of how much the climate goals will cost Norway.

Bottom Lines

As much as I appreciate others calling out the bloody nonsense passing for both conventional wisdom™ and its transmogrification into policy™ (sic) proposals, CO2-related issues are hare-brained schemes.

We may not know, exactly, how much CO2 mankind can, would, or should emit, but we do know enough, I’d argue, about what we don’t know:

You see, the Climate Change™ scam is clearly about the following:

it’s mainly a grift-and-psy-op, which permits gov’t to tax you for air use (CO2 emissions™) in exchange for future benefits they cannot estimate

the reason why there are neither cost nor benefit estimates are, in my view, because there’s no way this could be done in a way that is decently accurate and make a good case for doing so

a low-to-zero carbon emission world is a world that’s very poor relative to the present, with a much smaller population as low-carbon agriculture cannot sustain 8+ billion people (for the globalists, this is a clear win)

but doing something™, or at least being perceived as cosplaying alike, inflates the ego and gives some meaning™ to the worst people (as an example, Norway’s PM Støre was asked on TV while campaigning why the gov’t mandates the spraying of so many pesticides and other poisonous materials on produce—and replied that he’s ‘buying organic only’)

You can’t hate big gov’t enough.

Plus, you’ve gotta stop relying on experts™ and legacy media to guide you, that is, except to figure out how to talk to normies.

And then there’s the entire aspect of why pay taxes? (Because otherwise men with guns will show up at your doorstep.)

Any kind of such tyrannical régimes in history has fallen, some sooner and others later.

As a conclusion, I’ll cite a bit more from Mr. Smil’s report, at first from the section entitled ‘Realities vs. Wishful Thinking’:

Denmark, with half of its electricity now coming from wind, is often pointed out as a particular decarbonization success: since 1995 it cut its energy-related emissions by 56 percent (compared to the EU average of about 22 percent)—but, unlike its neighbours, the country does not produce any major metals (aluminum, copper, iron, or steel), it does not make any float glass or paper, does not synthesize any ammonia, and it does not even assemble any cars. All these products are energy-intensive, and transferring the emissions associated with their production to other countries creates an undeservedly green reputation for the country doing the transferring.

Now you also know why Denmark is a shitty role-model in the real world. Plus, you now also know how the Western success™ of decarbonisation™ has been achieved: by moving these ‘dirty’ processes abroad, mostly to China (but there’s more to note, such as the taking-apart of decommissioned ships in the world’s poorest places, such as Bangladesh or the like).

The latest International Energy Agency World Energy Outlook report confirms that conclusion. While it projects that energy-related CO2 emissions will peak in 2025, and that the demand for all fossil fuels will peak by 2030, it also anticipates that only coal consumption will decline significantly by 2050 (though it will still be about half of the 2023 level), and that the demand for crude oil and natural gas will see only marginal changes by 2050 with oil consumption still around 4 billion tons and natural gas use still above 4 trillion cubic meters a year (IEA, 2023d).

Wishful thinking or claiming otherwise should not be used or defended by saying that doing so represents “aspirational” goals. Responsible analyses must acknowledge existing energy, material, engineering, managerial, economic, and political realities. An impartial assessment of those resources indicates that it is extremely unlikely that the global energy system will be rid of all fossil carbon by 2050. Sensible policies and their vigorous pursuit will determine the actual degree of that dissociation, which might be as high as 60 or 65 percent. More and more people are recognizing these realities, and fewer are swayed by the incessant stream of miraculously downward-bending decarbonization scenarios so dear to demand modelers…

Belief in near-miraculous tomorrows never goes away. Even now we can read declarations claiming that the world can rely solely on wind and PV by 2030 (Global100RE-StrategyGroup, 2023). And then there are repeated claims that all energy needs (from airplanes to steel smelting) can be supplied by cheap green hydrogen or by affordable nuclear fusion. What does this all accomplish besides filling print and screens with unrealizable claims? Instead, we should devote our efforts to charting realistic futures that consider our technical capabilities, our material supplies, our economic possibilities, and our social necessities—and then devise practical ways to achieve them.

Yet, with even (sic) mildly dissenting voices, such as Øystein Sjølie, basically using his faculties to depart from the official narrative, I fear radical, or fundamental, opposition to such hare-brained schemes is not yet mature enough to actually propose alternatives that are both realistic and practical.

Vaclav Smil’s thoughts are very well worth your time, I think, esp. as these point out that the mad dash to stop CO2 emissions are—a forlorn hope, if that’s the right word.

In the end, reality has a way of asserting itself, although with both leaders™ and populations bamboozled and brain-addled to such degrees after decades of brain-washing, the nightmarish slumber of Westerners will continue a bit longer.

This will bring about a very, very rude awakening before too long, though, as well as the need for a reckoning, incl. judicial review of what the current régime has done.

I’ve read this report—which dates back to 2020 (!)—and it provides these gems:

There are 14 different fiscal incentives in place bearing on vehicles, fuel or road use. All of them are in some way CO2-differentiated. Zero exhaust emission vehicles (ZEVs), i.e. battery and fuel cell electric cars, are wholly or partially exempt of the first nine of these…

The fuel tax rate in 2019 was NOK 6.43 = € 0.637 per liter of gasoline and NOK 5.16 = € 0.488 per liter of diesel, corresponding to NOK 2770 = € 286 and NOK 1940 = € 200 per ton of CO2, respectively, all figures being net of (25 per cent) value added tax (VAT)…

It is a sobering and educational fact that the price of carbon facing Norwegian automobile owners and users exceeds € 1250 per ton of CO2 .

For light and heavy duty commercial vehicles the corresponding prices have been conservatively estimated at € 500 and € 200 per ton of CO2 .

These carbon prices probably come a long way to explain the record fast market uptake of zero emission passenger cars, the slower penetration of electric LCVs, and the relative lack of innovation within the heavy duty freight vehicle segment.

Can the Norwegian recipe be replicated elsewhere? The answer is a conditional yes [be afraid, be very afraid].

The recipe consists in taxing internal combustion engine vehicles rather than subsidizing electric ones. In every European country except Denmark, introducing a Norwegian style set of fiscal incentives [what a piece of BS] in place of the present automobile taxation and subsidization regime would likely bring massive amounts of new revenue into the public treasury (Østli et al. 2020). Public finance constraints are, in other words, no argument against the Norwegian incentives.

If you’re not outraged at these prospects, consider the policy propositions for the introduction of such policies™ elsewhere:

Here, too, things are worse once one looks closer (references omitted; p. 26):

Applying a 60 percent correction would raise McKinsey’s estimate of the cost of global decarbonization to $440 trillion, or nearly $15 trillion a year for three decades, requiring affluent economies to spend 20 to 25 percent of their annual GDP on the transition. Only once in history did the US (and Russia) spent higher shares of their annual economic product, and they did so for less than five years when they needed to win World War II. Is any country seriously contemplating similar, but now decades-long, commitments?

Citing new orders for airplanes and cruise ships, as well as their implied continued use of fossil fuels, much of which revolves around coal consumption. Here’s Smil’s conclusion (p. 28):

Too many realities point to the same conclusion: there will not be cuts in fossil carbon of anywhere near 50 percent by 2030—and no zero carbon by 2050.

Norway faces a very real danger from a different direction:

The tax on the very rich, and the migration-tax. A modest estimate made by people here in Sweden is that it cost (net) Norway 20 000 000 000 Norwegian Crowns the /first/ year, and that the effect in lost business-ventures, investments and people taking their business elsewhere or not bothering to start on may well lead Norway straight into a deep recession in a few years.

Which of course will cause the Socialist Democrat-party to tighten the clamps, since their basic mindset is "Obey because we know better than you" - and then they'll start dipping into the oil-funds for real. Expect the oil funds to be drained before 2040-2050, if so.

Probably all governments of the world are remote controlled idiots and criminals doing only what their psychopathic masters want them to do. They don't give a shit about the people.