100% EVs 'a Utopia', Leaving 'Banning' Gas and Diesel Cars the 'Only Option'

That is, according to news™ coming out of Norway, the world leader in virtual-signalling, as gov't handouts for EV adoption (paid for by everybody) are reduced, reality comes knocking at the door

Every now and then, there are revelatory pieces in legacy media, and a few days ago, I found just one of these in the business section of the Norwegian outlet nettavisen.no.

It relates directly to the recent piece on EVs that discussed the alleged ‘ban’ of combustion engine-powered cars, which had been dismissed in perhaps the most Norwegian way:

from 2035, the EU will stop selling new cars that run on classic petrol and diesel. This will be achieved through a high production tax on new cars, not a ban…taxes will be so high that for most people the electric car will be the preferred first choice.

Of course, this will then be celebrated, at some point, as ‘rational choice theory 2.0’ and it won’t be discussed in history of political science courses as ‘picking winners and losers’ or, more simply, top-down state-directed interventionism. For ‘more’ on this wonderful development, please see:

Today, we’ll discuss how that ‘stop-gap’ measure of proposing to level sky-high taxes on one consumer product (regular cars) while offering tax breaks and other goodies for other products (EVs) is going.

According to the below piece, I surmise it’s not going well, but read for yourself (translation, emphases, and [snark] mine).

EVs: A Clear Message: The Goal of 100% Electric Cars in Norway is Utopian

4 out of 10 Norwegians do not want an electric car. Experts believe they still do not meet many needs.

BAN [the] ONLY SOLUTION: Jonathan Parr is head of analysis at used car dealer Rebil. [this is perhaps the most Norwegian way of doing things, and I kinda could stop here because the below piece is all about that—but it offers a few insights I’d think you would want to read]

By Magnus Blaker, nettavisen.no, 26 Oct. 2025 [source]

The original plan was that this year only electric cars would be sold in Norway—whether they were vans or cars.

For vans, we are miles away from the goal, but we are also a long way off for passenger cars.

It was expected that the taxes on both petrol and diesel cars would skyrocket this year to reach the target, but to the surprise of many, the government never chose to do this.

Many Norwegians don’t want an electric car

A new survey conducted by InFact for used car retailer Rebil clearly shows that electric cars are not wanted by everyone.

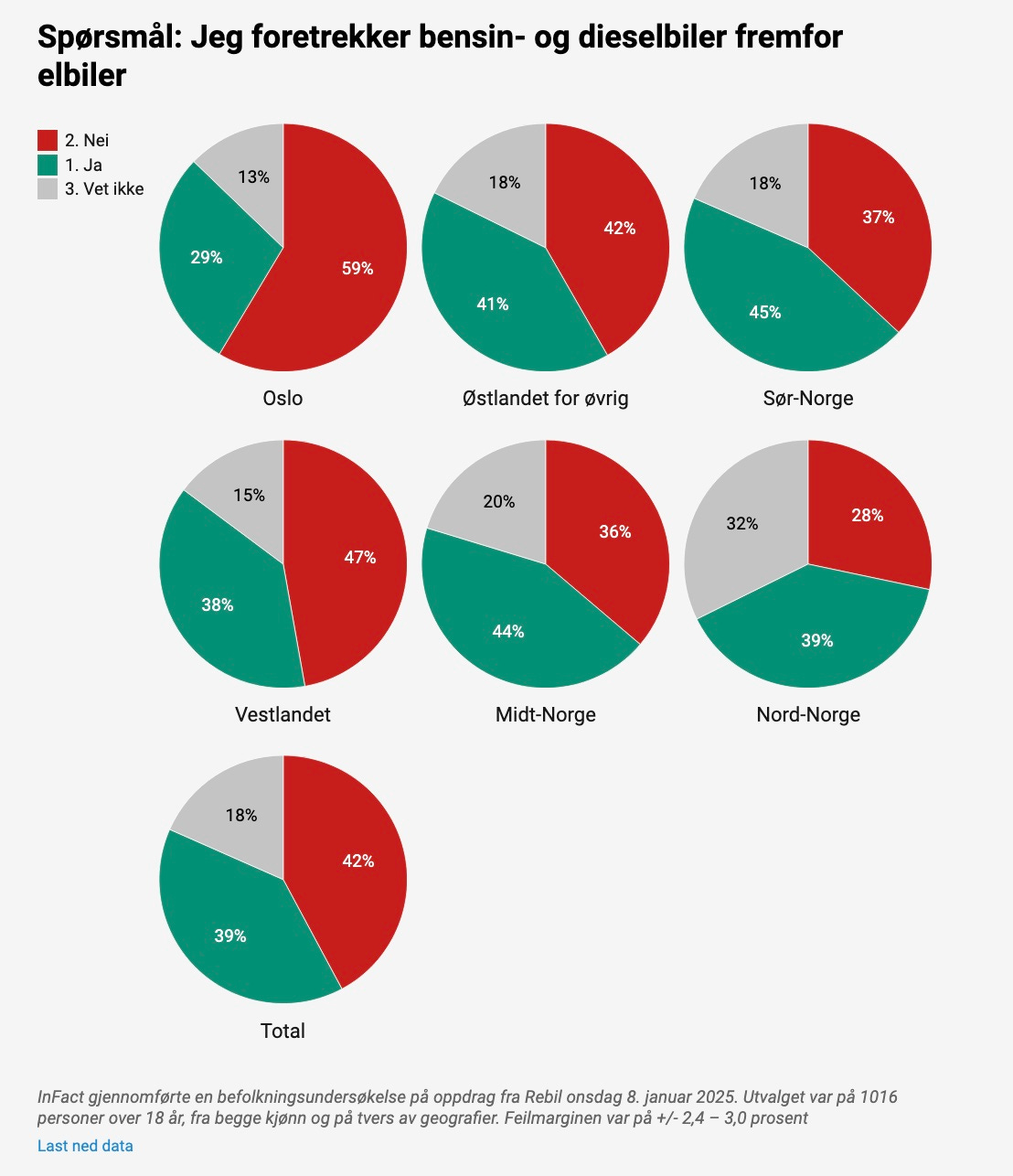

Question: I prefer petrol or diesel cars over EVs [red = no; green = yes; grey = don’t know; note the none-too-subtle programming via colour-coding]

InFact conducted a population survey on behalf of Rebil on Wednesday 8 Jan. 2025. The sample was 1,016 people over the age of 18, from both genders and across geographies. The margin of error was +/- 2.4-3.0%. [to download the data, sadly, you must venture to the article as this link is embedded in a JavaScript].

4 out of 10 say they prefer a car with a petrol or diesel engine, with major differences depending on where you live [fun fact: EVs are very impractical the higher north and/or further outside a city you live (see also the bottom lines for ‘more’ on this)].

This means that a 100% share of electric cars will not happen by itself.

There is still a clear majority in favour of retaining the current electric car benefits [ah, you see, for decades the gov’t used taxpayer money to subsidise new EV sales—the price difference was 25%, and by awarding EV buyers a tax credit (paid for by everyone else), this explains partially how Norway got to where it is in terms of EV sales; for a long time (until these ‘benefits’ were reduced from 1 July 2023 onwards) there were other perks, such as permission to use bus/taxi lanes (petrol/diesel cars may not), free parking in downtown areas, and partially also free charging, to say nothing about taxes on petrol and diesel, as well as other taxes; this is changing now, with EVs getting incrementally more expensive—but they aren’t nearly taxed/as expensive to run compared to petrol/diesel cars; as of 2023, there were about 690K EVs (passenger cars) in Norway out of a total of 2.88m cars].

However, support for electric car benefits is highest among those with good finances, and lowest among those with poor finances [oopsie, who would have thought that buying a quite expensive EV and operating it might not be for the proles and the hoi polloi].

The biggest EV benefit today is exemption from VAT on the purchase of a new car [that is the main perk I alluded to above, but sadly this is mischaracterised to a degree indicative of the piss-poor state of legacy media: it’s a tax credit—VAT on new cars (and many, many other goods) is 25%, and since these are taxes that aren’t paid by buyers of new EVs but by everybody else, ‘those with good finances’ are effectively subsidised by ‘those with poor finances’ (also tells you a lot about the actual state of Norway]. This is a benefit that isn’t particularly relevant if you can’t afford to buy a new car anyway [given all the uncertainty about future prices for fuel, taxes, or bans (or a combination thereof), I recommend not buying a new car in the first place; in Norway, there is no 25% VAT surcharge on used cars, and a new car will massively loose value the moment you sign the acquisition papers].

‘Needs that EVs don’t fulfil as well’

Jonathan Parr, Head of Analysis at Rebil [that is the gentlemen who is pictured above net to the ‘ban the only solution’ caption], is clear about what this means:

The electric car target [of 100% EVs] is a utopia [at least some truth here]. Large parts of the population simply prefer petrol and diesel cars.

Many people have needs that EVs don’t fulfil as well. For example, some people need cars that can tow heavy trailers and transport cargo without greatly reducing their range. In addition, many people live in areas with limited access to fast chargers, such as Finnmark [or literally anywhere outside city centres].

He also believes that the loss of EV benefits [remember: these perks were borne by every taxpayer while the benefits accrued to ‘those with good finances’] has made attitudes towards electric cars more lukewarm:

In 2023, the VAT exemption for electric cars over NOK 500,000 disappeared. In May [2024], electric cars were denied access to public transport lanes in the Oslo area. Toll costs and parking fees have increased, and in July [2024], the EV exemption from road pricing was removed [and now you can observe ‘rational choice’ knocking on the doors of ‘those with good finances’, and guess what this reality-check is doing].

Norwegians are world champions [of EV adoption] so far, and we’ve come a long way towards achieving the goal of a 100% share of electric cars in new car sales [it briefly reached north of 90% in summer last year, but it’s partially a dirty trick as used car sales, if for instance this piece by NRK from July 2023 is an indication: among other things, the above-related drastic changes in acquisition and operating costs for EVs meant that used cars, esp. petrol/diesel cars, are now selling like warm buns on a Sunday morning; too bad that much of this isn’t captured by official statistics as they only account for ‘second-hand cars’ but not for every sale thereafter]. But the day petrol or diesel cars are no longer sold in this country, it will probably be because the authorities have banned them [and this is the main take-away here].

Even though new car sales in Norway last year were 89% electric, the used car market is totally dominated by petrol and diesel cars. [Mr. Parr] ‘That's important to remember if you think new car sales show the entire trend.’

Rejects Old Prejudices

Nettavisen asks Parr whether this might be an old prejudice, given that new electric cars often have a range of 40 kilometres even in the winter, and even the børstraktor [meant is big fat limos driven by financial hucksters] Mercedes G-class has now become an electric car:

Some people have real range needs that are still not covered by electric cars. This may involve pulling trailers and other loads over long distances, while others live in places with poorer access to fast chargers, for example in Finnmark.

He believes that uncertainty is crucial:

Choosing a car is mostly about price, but also a lot about habits, both in terms of make, model, and usage. If the difference between the purchase price and running costs isn’t too great, many people prefer to choose the safe option.

Many people are probably worried about range without necessarily being concerned about usage. If you’ve never owned an electric car, range anxiety can be particularly acute. The advice is to familiarise yourself with how good the range actually is on the new cars, which are also getting better all the time.

A Personal Impression of Driving an EV

At this point, I shall declare the following: as my own car (petrol) was in the garage for the past two weeks, I was using a small Renault Zoé EV that I was offered while my car was unavailable.

As you know, I live on the outskirts of a small rural town (pop. around 2,200) where we own a small farmstead. It’s a 5-6 minute drive to get to the centre of town where there are a handful of chargers, but you can also plug the EV into a regular socket (it just takes ages to charge even that small car, i.e., 24+ hours).

Driving is a bit odd, because you never really know about the range. The display will give you indications (in % and km to go) of the battery status, and with reactive charging (i.e., the battery charges when you’re not accelerating), this will vary even if you merely drive to the grocery store and back.

I also live at 325m above sea level while the small town is at the coast, meaning that in addition to winter temperatures affecting range and battery status, driving up or down also affects range considerably.

All told, my biggest concern isn’t this kind of uncertainty per se (although supremely annoying, I can imagine one get’s used to it over time), but that you never really know how far you can drive. Add to that the issue of pulling a trailer (I live on a farm) or driving with a lot of heavy stuff in the trunk, which also decreases the range. We had a few days with quite cold temperatures (below -10 degrees C), and weather like this also decreases the range despite no changes in battery status.

I suppose my neighbour put it best: small EVs for city people or the like are quite o.k. in terms of expectations, use, and range requirements; if you require anything else, incl. greater range to, say, drive 100km in one direction and back without charging, your option is a much bigger—and hence very much more expensive—EV.

Yesterday, I got my petrol car back, and while it’s a crappy piece of junk (a 2017 Peugeot 2008, which I bought second-hand well before moving to a farm), I’ll drive it some more before I’m switching to another used car, most likely a diesel pick-up or van, which is way more useful for my purposes.

Bottom Lines

Don’t believe the hype; there are so many other issues with EVs beyond those already mentioned in the above both in the article and my personal reflections on EV use.

EVs are not only hundreds of kilograms heavier than regular cars (mainly to the batteries), they also have a commensurate heavier impact on roads (which thus become more expensive to maintain and/or build).

In addition, while I’m unsure about the exact ratio, there are clear signs that EVs use way more copper than regular cars; I’ve seen, certainly depending on car type/size, estimates of up to 80% more. See also this website here.

If at this point you’re worried about environmental impacts of, say, lithium mining and slave-labour aspects, may I recommend Siddharth Kara’s Cobalt Red: How The Blood Of The Congo Powers Our Lives (St. Martin’s, 2023).

I’d add another aspect here: copper prices have risen by a factor of 8 in the past 25 years, and if you don’t think these will affect EV prices, well, then I can’t help you. The USGS notes that ‘copper has become a major industrial metal, ranking third after iron and aluminum in terms of quantities consumed’.

And that’s before we’re talking stuff known from other raw materials, most notoriously ‘Peak Oil’, that is, the relationship between economically recoverable amounts vs. current and, perhaps more crucially, future demand.

And this is where this all gets super-hairy: if, for the sake of the argument, we assume that 50% of available reserves may be economically recoverable, let’s see what the Int’l Energy Agency envisions from 2020-40: you saw that correctly—business as usual means drastic increases of EV-related copper use, with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals indicating even higher copper demand (two- or threefold).

From Statista’s summary:

[There was a] nearly 30 percent increase in global copper consumption in 2022 compared to 2010…total global copper production from mines amounted to an estimated 22 million metric tons in 2023, which similarly amounted to an increase of almost 30 percent since 2010 [i.e., we’re effectively running to stand still]

The world’s leading copper producing countries include Chile, Peru, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo [oh, look, please read Cobalt Red]. Chile produces nearly one quarter of the world’s copper, and is also by far the country with the largest copper reserves…

Global copper consumption has steadily increased in recent years and currently stands at some 26 million metric tons. Forecasts for global copper demand show the same trend. Copper prices have remained relatively stable over the last decade (on an annual average price basis), reaching a record high in 2021.

And now multiply this by the factor 2-3 to reach the SDGs by 2040, although it took 12 years and God knows how much investment to grow production by 30%.

Also, note that it’s not ‘just’ copper that’s required for the UN/Club of Rome/WEF ‘energy transition’, as this helpful piece from the Int’l Energy Agency clearly shows:

The global clean energy transitions will have far-reaching consequences for mineral demand over the next 20 years. By 2040, total mineral demand from clean energy technologies double in the STEPS [Stated Policies Scenario] and quadruple in the SDS [Sustainable Development Scenario].

In both scenarios, EVs and battery storage account for about half of the mineral demand growth from clean energy technologies over the next two decades, spurred by surging demand for battery materials. Mineral demand from EVs and battery storage grows tenfold in the STEPS [that would be ‘business-as-usual] and over 30 times in the SDS [the UN/Club of Rome/WEF’s wet dreams] over the period to 2040. By weight, mineral demand in 2040 is dominated by graphite, copper and nickel. Lithium sees the fastest growth rate, with demand growing by over 40 times in the SDS.

And now ask yourself: does that look even remotely plausible? I mean, in the absence of WW3 or 4, and with a strong economy focused on extraction, refining, and manufacturing—I submit that it is virtually impossible to grow even a single raw material category, such as copper, by these leaps and bounds.

Doing so would be historic, by which is meant these growth rates over such short periods of time—it’s a mere 15 years to 2040—have never been achieved in the past. Yes, AI and advances in robotics might do something about this, but there are physical limits, to say nothing about the staggering amounts of debt, public and private, that also, and rather negatively so, will affect investments.

So, EVs are a pipe dream for some, a grift for early adopters, and the ultimate boondoggle, a prize they might share with robotics, ‘S.M.A.R.T.’ solutions™, and many other digital things that are, frankly, unsustainable given the material, economic, and price constraints.

EV adoption would never have taken off as it did if it weren’t for massive gov’t handouts (picking winners and losers), and whatever their benefits from an emissions point of view, it’s not even clear that a lifecycle analysis—such as this meta review by Shrey Verma and colleagues from 2022—speaks in favour of elevating one category (carbon emissions) while dismissing or ignoring all others:

With the adoption of EV there is a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) but there is an increase in the human toxicity level due to the larger use of metals, chemicals and energy for the production of powertrain, and high voltage batteries. And in terms of cost it has flexible pricing as there is uncertainty in pricing of future gasoline and electricity mix, higher initial cost at the time of purchasing due to higher pricing of battery.

We note, in passing, that there’s yet another aspect that must be considered (but hasn’t so far):

The environmental impact [sic] associated with the vehicle manufacturing phase, fuel cycle phase, use phase and recycling phase of the EVs need to be analysed.

Meaning—we don’t know that, and I’d submit that if these environmental impacts are included in any such lifecycle analysis, adoption of EVs will likely not have a better overall impact than, say, cars running on petrol or diesel.

(I do have access to the full paper, which we may discuss in a separate post, if you wish so; if you’d like to read the paper, drop me an email.)

We’re flying blind, no-one wants to know, and the topic of insanely high, and thus implausible, if not impossible, material demands is entirely avoided.

This won’t end well, esp. as any kind of economic and/or financial problem (crash) will significantly curtail investments in the expansion of production for many years.

And that’s before we’d account for oil and its derivatives, esp. diesel fuel, which powers virtually all machinery required for mining.

Sooner or later, something will give: what will be the first thing to crack?

It's a trillion-dollar global scam, and that's something I've claimed in conversations ever since I learned Obama was pouring billions onto Musk to get him started.

There's not enough REMs, for starters. There's not enough production potential. A man from Chalmers Technical School in Gothenburg had a look at production logistics for batteries the other year: his conclusion was that if the global production capability when it comes to EV-batteries was turned up full and the batteries only sold to Sweden, it'd still take at bare minimum 20 years to replace all the private cars. Meaning "personbilar" only. No trucks, lorries, vans, 18-wheelers, et cetera. 10 000 000 cars needs replacing here. Plus charging capability. Plus electricity production. Plus a grid capable of handling millions of EVs being hooked up to chargers at the same time. Plus...

None of that exist, there's no budget to create the infrastructure, there's zero gain for the state to invest in it, and "the market" certainly won't invest tens or hundreds of billions in infrastructure (the fiction called "the market" never invests in infrastructure - anyone studying the history of post-WW2 liberal capitalism - aka neo-feudalism - learns that immediately).

Grift, scam, fraud is all it is. Tulips from Amsterdam, basically. And by inveigling the scam into politics, it makes it nigh-on impossible to stop.

A neighbour here, from the next village (just 20km, that means neighbour :) ) is a fan of EVs. Also, he is a local politician for the old Communist party, so he is pretty much obligated to love EVs and dislike Musk. He recently told me about his new one. Can't recall the model but I do remember the important bits: with a fully loaded cat, and a fully loaded trailer attached (850+850 kilos), he got almost 100km out of it. That's a new EV, a new model, top-of-the-line battery, with re-charging function using friction et cetera to "get back" some power when rolling down-hill. If I understood him correctly.

He seemed to me to have that earnest, almost pleading, tone that someone may have when they subconsciously realise that they made a poor decision they are now looking for moral support for, to make their fail hurt less.

On top of the cost of the EV, he also needs a heated garage with a real concrete floor; the costs do add up, no?

Meanwhile, our diesel pick-up truck can spend the night in an unheated tent in -30C and will start on the first try, without using starter gas, and can pull the same load an entire day on a full tank.

Or to put it as Hayek and Friedman might have: if it needs subsidies to be viable, it's not viable.