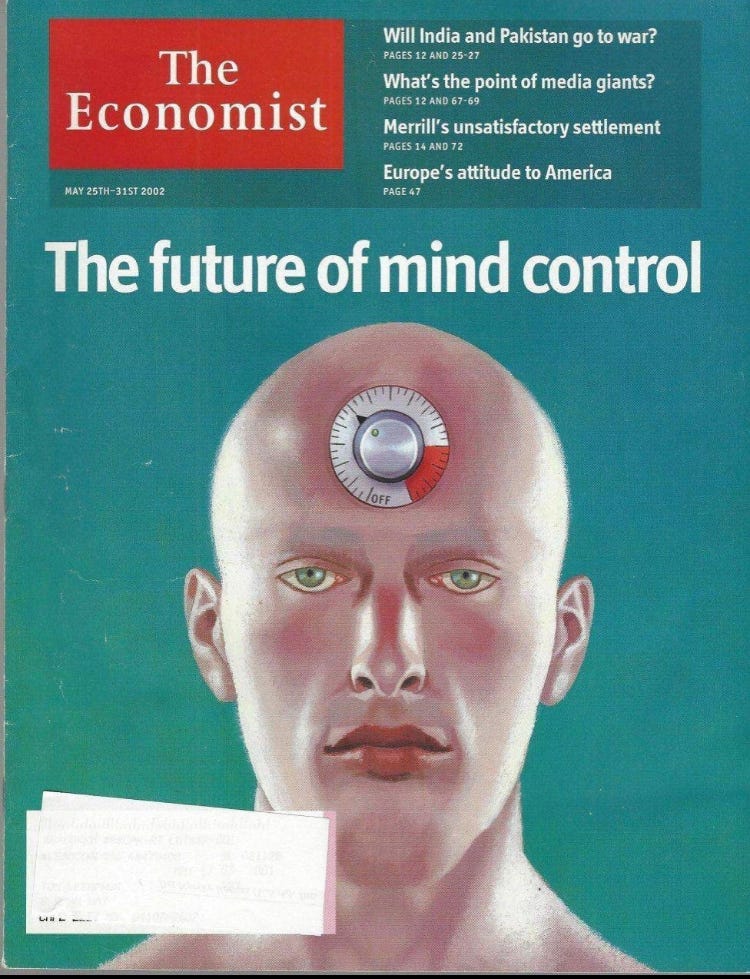

'The Future of Mind Control'

What did The Economist know back in 2002 and how much of it has become reality by now?

This is another piece from The Economist, and for an older—seemingly eerily prescient—posting on this notion, see here:

Today, we’ll go back to 2002, and here’s what The Economist’s editors wrote (emphases mine).

The Future of Mind Control

Via The Economist, 23 May 2002 [source]

People already worry about genetics. They should worry about brain science too

Caption note: look closely at the knob—the ‘red’ area starts in 2025, if you count the lines as years…

In an attempt to treat depression, neuroscientists once carried out a simple experiment. Using electrodes, they stimulated the brains of women in ways that caused pleasurable feelings. The subjects came to no harm—indeed their symptoms appeared to evaporate, at least temporarily—but they quickly fell in love with their experimenters.

Such a procedure (and there have been worse in the history of neuroscience) poses far more of a threat to human dignity and autonomy than does cloning. Cloning is the subject of fierce debate, with proposals for wholesale bans. Yet when it comes to neuroscience, no government or treaty stops anything. For decades, admittedly, no neuroscientist has been known to repeat the love experiment. A scientist who used a similar technique to create remote-controlled rats seemed not even to have entertained the possibility. ‘Humans? Who said anything about humans?’, he said, in genuine shock, when questioned. ‘We work on rats.’

Ignoring a possibility does not, however, make it go away. If asked to guess which group of scientists is most likely to be responsible, one day, for overturning the essential nature of humanity, most people might suggest geneticists. In fact neurotechnology poses a greater threat—and also a more immediate one. Moreover, it is a challenge that is largely ignored by regulators and the public, who seem unduly obsessed by gruesome fantasies of genetic dystopias.

A person's genetic make-up certainly has something important to do with his subsequent behaviour. But genes exert their effects through the brain. If you want to predict and control a person's behaviour, the brain is the place to start. Over the course of the next decade, scientists may be able to predict, by examining a scan of a person's brain, not only whether he will tend to mental sickness or health, but also whether he will tend to depression or violence. Neural implants may within a few years be able to increase intelligence or to speed up reflexes. Drug companies are hunting for molecules to assuage brain-related ills, from paralysis to shyness (see article). [it took about two decades, if this study by Rashid & Calhoun (2023) is any guide]

A public debate over the ethical limits to such neuroscience is long overdue. It may be hard to shift public attention away from genetics, which has so clearly shown its sinister side in the past. The spectre of eugenics, which reached its culmination in Nazi Germany, haunts both politicians and public [what a misleading sentence: whence did eugenics come from—the UK—is omitted casually, as are other circumstances]. The fear that the ability to monitor and select for desirable characteristics will lead to the subjugation of the undesirable—or the merely unfashionable—is well-founded [dare I mention the ‘Covid’ thing now?].

Not so long ago neuroscientists, too, were guilty of victimising the mentally ill and the imprisoned in the name of science. Their sins are now largely forgotten, thanks in part to the intractable controversy over the moral status of embryos. Anti-abortion lobbyists, who find stem-cell research and cloning repugnant, keep the ethics of genetic technology high on the political agenda. But for all its importance, the quarrel over abortion and embryos distorts public discussion of bioethics; it is a wonder that people in the field can discuss anything else [what a strange paragraph: isn’t human offspring, a few days old, going to become a human if not ‘aborted’ (killed)?].

In fact, they hardly do. America's National Institutes of Health has a hefty budget for studying the ethical, legal, and social implications of genetics, but it earmarks nothing for the specific study of the ethics of neuroscience [that’s an exaggeration, if data showing US$ 5+ billion of funding by 2013 are any indication]. The National Institute of Mental Health, one of its component bodies, has seen fit to finance a workshop on the ethical implications of ‘cyber-medicine’, yet it has not done the same to examine the social impact of drugs for ‘hyperactivity’, which 7% of American six- to eleven-year-olds now take [this share is much higher now; as this 2018 PLOS paper holds, its usage ‘doubled’ over the preceding (2006-16) decade]. The Wellcome Trust, Britain's main source of finance for the study of biomedical ethics [sic], has a programme devoted to the ethics of brain research, but the number of projects is dwarfed by its parallel programme devoted to genetics.

Uncontrollable Fears

The worriers have not spent these resources idly. Rather, they have produced the first widespread legislative and diplomatic efforts directed at containing scientific advance. The Council of Europe and the United Nations have declared human reproductive cloning a violation of human rights. The Senate is soon to vote on a bill that would send American scientists to prison for making cloned embryonic stem cells.

Yet neuroscientists have been left largely to their own devices, restrained only by standard codes of medical ethics and experimentation. This relative lack of regulation and oversight has produced a curious result. When it comes to the brain, society now regards the distinction between treatment and enhancement as essentially meaningless. Taking a drug such as Prozac when you are not clinically depressed used to be called cosmetic [I understand the word but I don’t know what is meant], or non-essential, and was therefore considered an improper use of medical technology. Now it is regarded as just about as cosmetic, and as non-essential, as birth control or orthodontics. American legislators are weighing the so-called parity issue—the argument that mental treatments deserve the same coverage in health-insurance plans as any other sort of drug. Where drugs to change personality traits were once seen as medicinal fripperies, or enhancements, they are now seen as entitlements.

This flexible attitude towards neurotechnology—use it if it might work, demand it if it does—is likely to extend to all sorts of other technologies that affect health and behaviour, both genetic and otherwise. Rather than resisting their advent, people are likely to begin clamouring for those that make themselves and their children healthier and happier.

This might be bad or it might be good. It is a question that public discussion ought to try to settle, perhaps with the help of a regulatory body such as the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority [click here for their website], which oversees embryo research in Britain. History teaches that worrying overmuch about technological change rarely stops it. Those who seek to halt genetics in its tracks may soon learn that lesson anew, as rogue scientists perform experiments in defiance of well-intended bans. But, if society is concerned about the pace and ethics of scientific advance, it should at least form a clearer picture of what is worth worrying about, and why.

Bottom Lines

What a strange Economist cover, eh? Given the magazine’s strong establishmentarian nature, this is quite…something to behold.

I suspect that, at this point, it is conceivable that the emphasis on ‘cloning’ and ‘genetics’ might be some kind of predictive programming to divert attention away from whatever (un)ethical ‘research’ is done with respect to our brains.

That last sentence—’if society is concerned about the pace and ethics of scientific advance, it should at least form a clearer picture of what is worth worrying about, and why’—is hilariously awesome in light of the WHO-declared, so-called ‘Pandemic™’.

Let’s hope we’ll eventually learn something there.

Articles such as this has been published roughly every 10-15 years, in magazines or academic journals, since the inter-war period if not earlier. While "mind control" is possible - witness civil servants and the public at large believing cloth masks stops virus particles - the total control variety of turning humans into programmable robots is not, and will probably remain impossible simply due to how the brain works.

AI and computers cannot handle paradox, self-contradictions, double-think, and so on; a human mind turned programmable will lose precisely that element of randomness that is intelligence's root cause.

At best you get a drone, and we can create that anyway: enhance cultural-societal and financial traits that increases the odds of worship of authority, and decreases independent thought and analytical same, and ability to switch "mental gears" between abstract and concrete thinking, to say nothing of the ability of metacognition.

Every other decade, natural scientists have claimed (or have let media claim) that they can perform the miracle of X by very simple means. And every time it is hypoerbole. Electricity would let us control people - it doesn't, it just fries the brain and destroys brainfunctions at random. Genetics would let us breed perfect humans - it doesn't, because not only is DNA too complex, it resets itself from artificial tampering after a few generations. Drugs? Same spiel. Social engineering? Same again.

And so on.

PS: The DNA resetting is quite funny. My wife's grandfather told about how they changed the gene deciding how man eyes a fruitfly would have and where on the body the eyes should go, resulting in fruitflies covered in eyes. After about 5-7 generations, they were back to normal. For some unknown reason, the change simply didn't stick. The DNA reset on its own. How and why is completely unknown; according to how we understand DNA, it shouldn't have been able to do that. DS

Techniques of propaganda and mind Control are already so effective that further pharmaceutical or mechanical intervention is simply unneccesary. COVID19 showed us how bad it’s gotten. You can basically manipulate large portions of the populace at will by clever use og propaganda and «nudging». This is precisely what Yuval Noah Harari meant when he said that «humans are hackable animals» - he wasn’t talking about the future. People have already been successfully «hacked» to regurgitate the thoughts and opinions the programmers want them to have.