The End of Urbanisation

Northern Italy shows the likely future: an empty countryside with oversized, if decaying, infrastructure that places enormous strains on what's going on in cities

As some readers may remember, I’m a history professor with specialisations in Europe’s past (ranging from the late 14th to the 19th centuries, so far)—and I’ve published extensively about urban-rural entanglements (4 monographs plus many articles).

When I came across the below piece, I was intrigued as the topic—an increasingly empty countryside across most countries (not only Western ones)—is a very odd, quite ahistorical, and momentous point in time.

But let’s begin at the beginning—and cover some essentials before we move on—and take a brief look at the UN Population Division’s 2018 World Urbanization Prospects (hence WUP 2018) whose executive summary (xix, emphases here and below, as well as [snark] mine) notes that

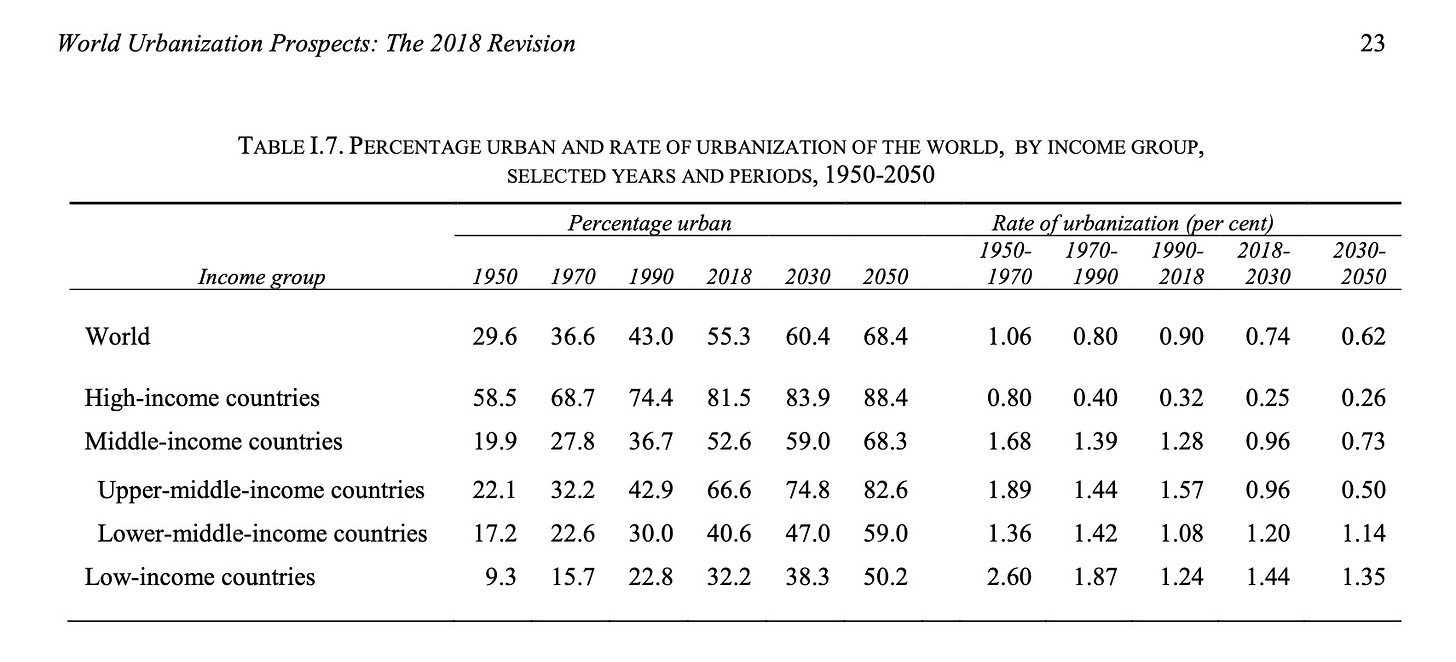

55 per cent of the world’s population residing in urban areas in 2018. In 1950, 30 per cent of the world’s population was urban, and by 2050, 68 per cent of the world’s population is projected to be urban…The most urbanized geographic regions include Northern America (82 per cent living in urban areas in 2018), Latin America and the Caribbean (81 per cent), Europe (74 per cent) and Oceania (68 per cent).

A bit further down on the same page, we learn that ‘between 1990 and 2018, the world’s cities with more than 300,000 inhabitants grew at an average annual rate of 1.8 per cent’, which is stunning. According to Our World in Data (although their graph is shitty), world population growth was around 2% in 1990—and has declined to .9% by 2023. In other words, cities with more than 300,000 inhabitants grow at twice the rate—right now—than the world’s human population. This trend is estimated to accelerate dramatically over the coming decades.

(As an aside, yes, the UN Population Division’s forecasts of human population levels were quite accurate, give or take a few tens of millions, as Hannah Ritchie documents in her essay over at OWID.)

Yes, the world’s population will continue to increase for some more decades mainly due to rising life expectancy as well as declining morbidity and mortality, but non of these aspects can gloss over a few simple facts:

In 1950, 59 per cent of the population in high-income countries already lived in urban areas, and this share is expected to rise further, from 81 per cent today to nearly 88 per cent in 2050 (WUP 2018, xix).

Where would additional city-dwellers come from? The countryside is quite literally emptied out, and migration from adjacent semi-peripheral countries—think Eastern to Western Europe—has virtually come to a halt as the former’s income levels are not that far behind the latter’s. Here’s a good table summarising these trends globally:

As far as trends and probabilities are concerned with respect to the next couple of decades, here’s the most salient take-away (WUP 2018, 24-5):

Over the next 32 years, the differences expected in urban population growth will accentuate the redistribution of the urban population that occurred during 1950-2018. Africa’s urban population is likely to nearly triple between 2018 and 2050, while that of Asia is likely to increase by over 50 per cent. With 1.5 billion urban dwellers in 2050, Africa will have 22 per cent of the world’s urban population, while Asia, with 3.5 billion persons residing in urban areas, will have 52 per cent.

I’m going out on a limb here—I think East Asians might pull it off to manage that massive bout of urbanisation without major problems; I have less hope for sub-Saharan Africa where the already existing massive slums will increase further, compounded by bad to in-existing sanitation will lead to drastically lower life expectancy and, possibly, bouts of epidemics reminiscent of 19th-century Europe (cholera, TBC, etc.).

Speaking of Western Europe (it’s in the ‘high-income countries’) once more, we note an average urbanisation rate in excess of 80% (and I’m including, all other things being equal, other such countries in East Asia and Northern America, although the below legacy media piece is from Europe, hence I’’ doing this). This translates into an already quite empty countryside— historically the origin of most city-dwellers. There may be some marginal gains across Western cities, but there’s neither much room (as in: space to be converted into metro areas) for growth left nor are there many people left in the countryside who would like to become urban residents.

That leaves (mass) immigration from outside the West as the only so far not too tapped reservoir of people to move/import into Western cities.

This is also where most attention is focused on: urban issues, including the planning of new, massive bouts of infrastructure investments—think: new subway lines, which are most likely boondoggles to begin with and whose prospects look dim—that are currently planned over several decades. These investments are little more than public-private work programs but they will not serve anyone due to population decline from the mid-21st century onwards.

And with the stage thus set, let’s move on to legacy media reporting, in their very own ways, about these prospects. The below piece comes to us via the Milanese daily Corriere della Sera, in my translation—how ‘fortunate’ that I hold a graduate degree in Italian—albeit with emphases and [snark] added.

The 33 villages in Trentino Where Nobody Wants to Live Offer Up to 100,000 Euros for Those who Move In

The Province of Trento will provide up to 80,000 euro for the renovation of a building (and up to 20,000 for the purchase). The villages are those that have lost the most inhabitants in recent years. To get the money, it is compulsory to live there for 10 years or rent it out at a moderate rent to someone who lives there

By Maria Parolari, Corriere della Sera, 18 March 2025 [source; archived]

In just a month and a half, the proposal should be approved and wherever you live in Italy—potentially from all over the globe—the dream of a peaceful home in Trentino could become a reality. This is due thanks to the contributions of the Autonomous Province of Trento. ‘It is a social cohesion measure, to repopulate some municipalities,’ explains Ileana Olivo, provincial manager of the task force that has identified the villages and will accompany the new residents there. ‘We are not asking for the ISEE [orig. indicatore della situazione economica equivalente is used to measure the economic status of families, i.e., your ISEE ‘score’ determines the level of gov’t welfare payments: what the task force manager is telling us here is—the funds to repopulate parts of Northern Italy will be disbursed irrespective of an applicant’s wealth and income], but for the renovators to bring new active citizens to the territory. We are talking about very small “marginal” municipalities, where the introduction of just five new family groups changes the life of a village’. [let that paragraph sink in: historically, Southern Italy—the mezzogiorno—was the area of mass emigration; now, this feature comprises the entire country].

Funds made available by the Province are non-repayable contributions [i.e., gov’t grants, not loans] to support the expenses of those who buy and renovate a property, to use it as a home or to rent it out at a moderate rent to workers or citizens who move their residence for ten years (starting from the completion of the work) to the property located in the municipalities of Trentino affected by the demographic decline [this is the key passage: the wave of the future]. These are all areas—33 towns—where abandoned houses and opportunities for building renovations are proliferating [why, oh why, am I thinking about lipstick being applied to pigs (no offence to the latter)?]. To remedy this problem, anyone who undertakes—for example—to renovate one of these properties in one of these municipalities will receive a contribution of up to 80,000 euros out of a total expenditure of 200,000 (up to 40% in historic centres and 35% outside). If someone from outside the municipality decides to buy a house in one of these areas, in addition to the amount to renovate it, he will receive up to 20,000 euros in acquisition aid [see what I mean? just imagine how long Western gov’ts will be able to finance all of this…].

Beneficiaries

The beneficiaries will be natural persons ‘who have or intend to acquire a right of ownership or enjoyment over a property and are allowed to apply for contributions up to a maximum of three units this to give unity to the renovation work, for example for restoring facades’, explains the Province. ‘The beneficiary must not be a resident in the area where the property unit is located, unless he or she is over forty-five years of age. Once the measure has been approved, explains Olivo, the Province will start collecting applications. ‘The measure is aimed at owners or future holders of real estate rights on properties that need upgrading to be inhabited’, Olivo explains, adding:

We do not want to exclude the possibility of someone buying a dilapidated property and using these funds to renovate it. We will draw up rankings (of already accepted applications) for tranches of 3-4 months, so that work can begin as early as this year.

Timing of Contributions

After the four-month tranche, the administrative time is a maximum of 60 days to issue the contribution [talk about swift—desperate—disbursement of funds by the state]. As a projection, the fastest could collect and start work even at the beginning of September. There is no limit on the number of housing units, only the need for renovation work. Whoever applies for the contribution must, however, have already identified the property and indicated this in the application: ‘We are thinking, in order to avoid speculation, of involving real estate agencies and organising territorial tables, to connect demand and supply of houses’, Olivo explains. ‘But for the first tranche we will focus on those who are already owners and live outside the municipality. The aim is still to create a sense of community: every new arrival must be included and accompanied.’

The Decline in Residents

Studies carried out by the provincial statistics service (Ispat) have thus revealed 33 territories with a minus sign (ranging from -0.3% to -20% [imagine the latter decline in your community]), which have suffered a drop in residents over the last 10 years, obtained by ‘discarding’ municipalities with many tourist presences, where the drop in residents is due to the conversion of accommodation to short lets. Municipalities with a minus sign in front, explains the Province, selected by means of two indicators: ‘The municipalities’ demographic decrease index plus a composite indicator of tourism, which derives from the ratio between tourist presences and resident population and from the ratio between tourist presences and the average number of tourist presences in the province'.

The Municipalities Involved

As Olivo explains, there is still no precise list of territories, since the measure must by law be submitted to the Council of Local Self-Government and the competent committee of the provincial council for its opinion. But barring last-minute exclusions and surprises, among the 33 towns pre-selected by the provincial council there would be municipalities in Trentino Province, such as Val di Non, with Bresimo and Livo, Val di Sole with Rabbi, and the Hollywood-esque Vermiglio. In the Giudicarie Community, the ski resort Tre Ville, Bondone and Borgo Chiese. Then Terragnolo in Vallagarina, and Luserna, in the Magnifica Comunità degli Altipiani Cimbri. Also included a few kilometres from Trento are the municipalities of Sover and Giovo, in Val di Cembra, and those in Valsugana: Palù del Fersina, Castello Tesino, Cinte Tesino and Grigno. Around the ski facilities of San Martino di Castrozza and the thermal springs of Feltre, there are Primiero resorts such as Sagron Mis, Mezzano and Canal San Bovo. There is also skiing in the Fiemme and Fassa valleys, with Valfloriana and Campitello di Fassa.

Resources

The total resources amount to EUR 10 million, allocated by the provincial government in the last budget allocation. ‘We have a capacity of 5 million euro a year, and an expected average amount of 50,000 euro per subsidised house,’ explains Olivo. We foresee the construction of 100 new properties, with the relevant resident households'. In addition, the Province, together with Trentino Marketing, once the measure has been approved, will launch a promotional campaign aimed at bringing the opportunities of its 33 municipalities into homes throughout Italy, and potentially the world.

Bottom Lines

The first (and only, I think) rule of ‘sustainability’ is—things that can’t be sustained, won’t be (and aren’t ‘sustainable’).

The most obvious of these things is—city living.

In ecological and economic terms, a ‘city’ may be defined as an area whose carrying capacity is greatly exceeded by the resident population. This necessitates both the importation of resources and facilitates centralisation and control by whoever runs such a place.

Importation of resources means cities are heavily dependent on their hinterlands, safety and security of transportation routes (trunk roads and railroad lines) and distribution systems (banks, supermarkets). There’s so many moving parts, this is a complex system, which indicates that there’s ever so many chances that things could go wrong (and at some point, they will).

If the rural areas are the source of most city-dwellers, once the countryside is (virtually) emptied out—which it is in ‘high-income countries’—urban growth derives from people who migrate from afar.

Logically, this means that these newcomers must also contribute to the future taxbase lest the highly bureaucratised central gov’t will run out of funds before too long. Doing so means the onset of urban decay, blight, and the eventual flight of city people elsewhere (think Detroit). This inevitably leads to the abandonment of the now-oversized cities.

Note, also, that this is a vicious cycle™ (much like the circular economy) that has a logical endpoint: at some point, fleeing urbanistas run out of other places to migrate to and arrive, once more, where they left.

And that’s all assuming the human population is going to come down slowly and in a managed fashion (which I personally doubt it will): well before decline sets in, new construction will cease due to it being un-economical. After a certain point (also well before decline sets in), Mr. Market will overcome any politicians’ dreams—hallucinations.

For ordinary people this will bring massive changes: politicos™ will ‘safe’ money by cutting back on services, first in rural districts, later also among urban areas.

Shrinking cities means a lot of material that can and will have to be salvaged as, e.g., taking copper wires out of abandoned buildings or re-using steel beams, etc. will be more economical than importing all that stuff from halfway around the world. Craftsmanship will also make a comeback, of sorts, provided there’s enough people with commensurate skills that don’t depend too much on power tools.

Overall, the pace of live will slow down, which I think may not be the worst outcome.

In the medium-to-long term, the end of urbanisation will come, no matter how the UN Population Division spins this (the below is from WUP, 73):

The percentage of cities estimated to have lost population has remained steady during 1970-1990 and 1990-2018, at around 10 per cent (figure III.5, above). During 1970-1990, 63 cities with 300,000 inhabitants or more in 1970 experienced negative growth, most of which were in the United Kingdom, Germany and the United States of America. During the more recent period of 1990-2018, 95 cities with 300,000 inhabitants or more in 1990 experienced population decline, mainly located in the Russian Federation, Ukraine and other European countries.

More recently, since 2000, most of the cities experiencing population decline were located in low-fertility countries of Asia and Europe with stagnating or declining populations [that’s literally all ‘high-income countries’]. A few cities in Japan and the Republic of Korea (for example, Nagasaki and Busan) have experienced population decline between 2000 and 2018. Several cities in European countries such as Poland, Romania, the Russian Federation and Ukraine have lost population since 2000 as well. Shrinking populations in Central and Eastern Europe has resulted from challenging adaptation processes after radical shifts in economic organization and performance, and changes in political regimes or economic policy [see what I mean? It’s not a secret]. Shrinking cities, include several capital cities around the world, such as Bucharest (Romania), Colombo (Sri Lanka), La Habana (Cuba), Riga (Latvia), and Yerevan (Armenia). In addition to low fertility, emigration has also contributed to smaller population sizes in some of these cities [this compounds these demographic issues].

Cities experiencing both demographic and economic declines around the world face important challenges for planning their urban policies, as they need to redefine their economic strategies while developing adaptive policy instruments to address the realities of shrinkage [most Western cities still phantasise about growing further]. Today, 94 cities have declining populations, i.e. they lost population between 2015 and 2020. These cities are home to nearly 95 million people in 2018, and most of them are expected to continue shrinking in 2020-2030, so that by 2030 they would have lost 2.1 million since 2018. Globally, fewer cities (5 per cent) are projected to see their populations decline from today to 2030, as compared to the last 2 decades.

This is where the projection ends—in 2030.

Decline of the rural population in Western countries from 2018 until 2050 is summarised in Table II.3 (WUP 2018, 46), and in those countries cited—Italy (-40.5%), Germany (-33.5%), Poland (-37%), Japan (-46%), France (-35.4%), Spain (-41.7%), the UK (-33.3%), and Romania (-39.3%)—the decline of the rural population is massive.

Remember, this decline in rural residents means the countryside—which is pretty empty already (we’re at 83% urbanisation in ‘high-income countries’ in 2018)—will be further depopulated.

Thus follows, if cities are supposed to grow further, this growth will mostly come from elsewhere, placing massive strains on public coffers and social cohesion:

Bottom line—the next 2-3 decades will see massive change, and at some point, one or the other thing will have to give.

Better get ready for that breaking point.

Here's the official map for pop-dens for Sweden. As is usual with our official webpages, quality and usability is on a 1995-level of competence:

https://www.scb.se/contentassets/3bbd9712c3c54b68b271562998c2f6b6/befolkningstathet_5km_rutor2.png

Instead of providing a map where you can search for specific communes or towns or areas, this is what our official statistics authority can put together. They can't even make it fully zoom-able.

Anyway. I'm in one of the white areas, each square being 5x5 km. So where I live, there's "no population". Norway is much the same I guess. What's funny to me is that 200 people per sqkm is considered dense here; Malta is some 1 500+/sqkm. Tokyo I daren't even guess - I can feel the cortisol levels increasing just thinking about it.

In the interior, there lots and lots of towns that look like there's already been a war. Lesjöfors in Värmland is a prime example: boarded up windows on abandoned dilapidated and decrepit buildings right in the center of town, burned out husks of industrial buildings, and everything giving off the same feeling as did DDR right before the end: grey, old, worn out and worn down, and covered in dust, the landscape radiating hopelessness. Different from DDR, everything doesn't smell of boiled cabbage, and there are plenty of migrants engaged in the drug trade.

Let the cities collapse, I say. Slowly and controlled, and but let them collapse.

Here in Sweden for ten years now, there's a real migration of Swedes going on: to the countryside, if 40+ and abroad if younger. What isn't said out loud, but is obvious: they move away from Negros, Arabs, Afghans and so on.

Why not just admit it instead?

Complete uprooting- a Pentagon Brief given by Thomas P. Barnett on how the world will be split into two groups by mass migration. francesleader.substack.com/p/complete-uprooting