Dutch Researchers Reveal the True Cost of Mass Immigration

Spoiler alert: 'Westerners' are a net-positive while migrants from esp. the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa are Bottomless Sinks

Today, we’ll take a deeper dive into new insights from a bunch of Dutch academics from the University of Amsterdam. Published in summer 2023, the study—entitled ‘Borderless Borderless Welfare State: The Consequences of Immigration for Public Finances’—was written by Jan Van de Beek, Hans Roodenburg, Josep Hartog, and Gerrit Kreffer. It uses granular data from the Dutch gov’t to assess the net contribution/cost by immigrants by asking the following set of questions:

Do immigrants contribute to public finances?

Do welfare states attract and benefit immigrant groups?

Is immigration necessary to bear the costs of an ageing population?

What is the role of education and cultural factors in all this?

And what about the second generation?

In a sense, this is a follow-up posting to my recent dive into the UN Population Division’s ‘Report on Remigration’ (2001). Please find it here:

The study by Van de Beek et al., ‘Borderless Welfare State’ will form the largest part of what follows, and I encourage everyone to read it in its entirety.

If you’re short on time, here’s a podcast with Jan Van de Beek, which was posted by Aporia Magazine online in early December 2023.

Without much further ado, here’s a few key insights from the study; for readability, I’ve removed the references (which are there in the original); emphases mine.

From the Publisher / Book Jacket

A multidisciplinary team of four experienced researchers investigated this topic in the Netherlands. They had access to unique anonymised microdata from Statistics Netherlands on all inhabitants of the country. In estimating the fiscal impact of immigration, the net lifetime contribution of immigrants to public coffers was estimated by employing the method of generational accounting.

The result is this book, with the eloquent title Borderless Welfare State. It answers the questions, contains a wealth of previously unpublished information, and draws conclusions with strong policy relevance. The findings may inspire researchers and policymakers in other countries, particularly in Europe, with a comparable welfare state.

An earlier version of this book sparked debate in the Netherlands. The Dutch government stated that they did not need this type of information. One could only guess the underlying reason for this position. Is it the inconvenient message from Borderless Welfare State that, if immigration continues by the current numbers and composition, welfare states like the Dutch one become unsustainable?

Preface

In a way, this report can be seen as an update and extension of the CPB report Immigration and the Dutch Economy from 2003. That CPB report, among other things, calculated the costs and benefits for the treasury of non-Western immigration at the time. Since that report, the government has no longer calculated these tax costs and benefits of immigration in a general sense. This is striking because in the Netherlands just about everything that is relevant to policy is regularly monitored in all kinds of ways. And given its considerable size in the last decades, immigration to the Netherlands can certainly be considered policy-relevant.

The fact that the CPB report from 2003 has not received a full update is not least due to normative limitations. In this context, the late minister Eberhard van der Laan said in the NOS-journaal news program of 4 September 2009 that the cabinet is not interested in putting people along the yardstick of euros. The then director of the CPB, Laura van Geest, stated in an interview: “I don't think you should talk about refugees and start calculating something.” And Klaas Dijkhoff stated in 2016 as State Secretary for Security and Justice in response to parliamentary questions that the government does not evaluate citizens, but policy. Country of origin is personal data that, “in accordance with the principles of the rule of law, is not relevant to most policy areas,” says Dijkhoff.

There are three underlying – often implicit – arguments that play a role in this: ‘one should not calculate the value of a human life’, ‘one should not blame the victim’ and ‘one should not play into the hands of the extreme right’. None of these three arguments makes sense upon closer consideration.

Let's begin with the argument that one should not ‘calculate the value of a human life’. It is sometimes noted that it would not be ethically acceptable to calculate the costs and benefits of immigrants. Humanitarian reasons and human solidarity would oppose this. This argument is already very easy to refute for immigrant workers because their arrival is often defended on the basis of economic self-interest. But it doesn't really make sense for family immigrants and refugees either. Few residents would welcome immigrants at any cost, for example, for whom it does not matter whether immigration reduces their income by a small percentage or cuts their income by a quarter.

When assessing policy measures, costs and benefits are always weighed [not with the Covid modRNA shots], whether implicitly or explicitly. The introduction of new medicines in an insurance package, the safety measures at train-crossings, the legal regulations for working conditions, the height of sea dikes, the expenditure on defence, the installation of crash barriers along motorways, the list can be expanded effortlessly. The only real choice that can be made is between implicit – vague and unspecified, with one's head in the sand – and explicit, but with a clear awareness of the limitations of such calculations. We opt for the latter. Everyone is free to want to spend a lot or little on road safety, nature management and receiving refugees. Ultimately, that revolves around political considerations, but this should be done with a clear view of the costs and benefits.

Having insight into the costs and benefits also invalidates the other two arguments against calculating the costs and benefits of immigration. If the costs and benefits of immigration are known and continuously monitored, it is to be expected that the government will also focus more on successful immigration, for example by setting up a more selective immigration policy like that of Australia or Canada. In these countries, there is a selective immigration policy that is quite broadly supported by the population.

It can be expected that an admission policy that has a positive effect on the host society also contributes to the prosperity and well-being of the immigrants, after all, one will select those immigrants with the greatest chances of socio-economic and socio-cultural integration. But if immigration policy has a positive effect on both the existing population and the immigrants, this will also positively influence the existing population's views on immigration policy. This reduces the chances of blaming the victim because there are fewer immigrants who are doing badly and if there are problems, the blame falls on the failing – insufficiently selective – immigration policy. A logical consequence is that political parties that want to capitalize on dissatisfaction with the immigration policy will receive less ammunition as a result, so the hackneyed argument to ‘not play into the hands of the extreme right’ – whatever that may mean – falls apart.

There is one big but: the current immigration policy can hardly be made selective without a fundamental policy change. The reason is that the Netherlands is not sovereign when it comes to immigration. Immigration policy has been extensively internationalized and juridified. International treaties such as the UN Refugee Convention and European regulations and treaties largely determine who is or is not admitted to Dutch territory [same elsewhere in the EU]. This is probably an important explanation for the taboo on calculating the costs and benefits of immigration referred to above. Policymakers know that change is very difficult and involves major political risks, and so they view the topic as what public administration expert Ringeling calls a ‘prohibited policy alternative’. Setting taboos is simply one of the tools of the exercise of power.

Our hope is that this report will help to overcome this normative barrier and that it will lead the knowledge institutes in the Netherlands – Statistics Netherlands (CBS), CPB, SCP, WODC, NIDI and PBL – to set up a continuous policy monitor for immigration policy in general and the admission policy in particular. This immigration monitor should pay ample attention to the fiscal costs and benefits and other economic effects of immigration…

Policy-relevant, hyperlinked sections are listed on pp. 13-14.

Brief Summary

The essence of the applied method is that the costs and benefits of the entire remaining life course of immigrants are mapped out. We call the benefits minus the costs the net contribution. The calculations are based on anonymous data of all 17 million Dutch residents. The Dutch population is growing due to immigration. Of the over 17 million Dutch residents at the end of 2019, 13% were born abroad (first generation) and 11% were children of immigrants (second generation).

Government spending on immigrants is now above average for items such as education, social security and benefits. Immigrants, on the other hand, pay less taxes and social security premiums on average. When added together, the net costs of immigration turn out to be considerable: for immigrants who entered in the period 1995-2019 alone, these are 400 billion euros, an amount in the order of magnitude of the total Dutch natural gas revenues from the 1960s onwards. These costs are mainly the result of redistribution through the welfare state. Continuing immigration with its current size and cost structure will put increasing pressure on public finances. Curtailment of the welfare state and/or immigration will then be inevitable.

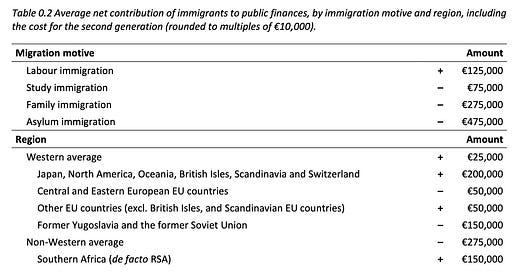

The average costs and benefits of different immigrant groups differ greatly. The report presents these differences. Immigration for work and study from most Western countries and a number of non-Western – especially East Asian – countries show a positive outcome. All other forms of immigration are at best more or less budget neutral or have a negative effect on the budget. The latter applies especially to the motives family and asylum.

The educational level of immigrants is very decisive for their net contribution to the Dutch treasury, and the same applies to their children's Cito scores (scores on a 50-point scale for assessing pupils in primary education). If the parents make a positive net contribution, the second generation is usually comparable to the native Dutch population. If the parents make a strongly negative net contribution, the second generation usually lags behind considerably as well. Therefore, the adage ‘it will all work out with the second generation’ does not hold true.

Immigration is not a solution to population ageing. If the percentage of those over the age of 70 is to be kept constant with immigration, the Dutch population will grow extremely quickly to approximately 100 million at the end of this century. Population ageing is mainly dejuvenation. Far fewer children are being born than is necessary to maintain the population. And immigration does not solve the dejuvenation. The only structural solution is an increase in the average number of children. Furthermore, immigration does not seem to be a viable way to absorb the costs of population ageing. This would require large numbers of above-average performing immigrants with all the consequences for population growth [meant is: those immigrants tend to have fewer children].

Immigrants who on average make a large negative net contribution to public finances are mainly found among those who exercise the right to asylum, especially if they come from Africa and the Middle East. The total population in these areas will increase from 1.6 billion today to 4.7 billion by the end of this century. Maintaining the existing legal framework, in particular regarding the right of asylum, does not seem a realistic option under these circumstances…

From the Long-Form Summary

[the below text isn’t from the ‘brief summary’ but follows Tab.02 on pp. 19]

For all immigration motives, Western immigrants seem to ‘perform better’ than non-Western immigrants. The difference is approximately €125,000 for labour and study immigrants, and €250,000 for asylum and family immigrants. The largest positive net contribution – €625,000 – is made by migrant workers from Japan, North America and Oceania. The largest net cost – also €625,000 – is for asylum migrants from Africa [no surprises here].

In isolation, only two categories seem favourable for Dutch public finances: study immigration from the EU, and labour immigration from Western countries (except Central and Eastern European countries), Asia (except the Middle East) and Latin America. However, if one takes into account the cost of family migration (chain migration), only labour migration from North America, Oceania, the British Isles, Scandinavia, Belgium, Luxembourg, France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Spain, Israel, India, Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan is unambiguously positive from a treasury perspective [if you’d need an up-to-date definition of ‘West’, there you go; line break added]

Study migration from the EU and EFTA, taking into account chain migration, is likely to be roughly budget-neutral or slightly positive. Study and labour migration from the rest of the world is at best budget-neutral and mostly negative, surprisingly sometimes very negative, given the motive reported to the Dutch Immigration and Naturalisation Service (IND). Family migration also, almost without exception, represents an often substantial drain on the Dutch treasury. Asylum migration is very costly in all cases…

Costs and benefits by generation and the importance of education and test scores [read: IQ of immigrants matters]

Immigrant groups of which the first generation yields substantial net benefits usually do not show the same outcome for the second generation. That generation – although well integrated – is usually roughly budget neutral.

Migrant groups of which the first generation has a (considerable) negative net contribution, usually have a second generation that also has a (substantial) negative net contribution. For those groups, the net present value of the net contribution of future generations will not offset the costs for the first generation. The quite common idea that ‘things will improve in future generations’ therefore does not apply when it comes to the costs and benefits of immigrants.

There is a substantial correlation between net life course contribution and educational attainment. Immigrants with a master's degree make a positive net life course contribution of €130,000 (non-western) to €245,000 (western [phew, I hold two doctorates ^_^]) against €515,000 for natives (rounded off to multiples of €5,000). Immigrants with at most primary education cost the treasury a net €360,000 (non-western) to €195,000 (western) over their whole lives compared to €235,000 for natives. A positive net contribution requires the immigrant to have at least a bachelor's degree or equivalent education, or skills that enable him or her to generate an income comparable to someone working at bachelor's level. That the Netherlands – unlike classic immigration countries – hardly selects on education level and skills causes a large part of the net cost of non-Western immigration.

Furthermore, a robust correlation exists between net contribution and scores on the so-called ‘Cito's End-of-Primary-School-Test’, a 50-point student assessment scale for primary education. Natives with the highest Cito score make a positive net contribution of (rounded) €340,000 over their live course. Natives with the lowest Cito score cost a net €440,000 over their life course. For the most common Cito scores, a one-point higher Cito score provides roughly €20,000 extra net contribution over the life course. For people with a second-generation migration background, there is a similar relationship between Cito score and net contribution, albeit at a considerably lower level. The net contributions of the western second generation are on average about €60,000 lower than of natives with the same Cito score. The non-western second generation on average even has a €170,000 lower net contribution than natives with the same Cito score. These differences are not caused by the Dutch education system, because immigrants with a certain Cito score hardly differ from natives with the same Cito score when it comes to final educational attainment. These differences arise after education, in the labour market [or before primary school, i.e., due to different cultural backgrounds, on which see below].

There are considerable differences in Cito scores between regions of origin and also between immigration motives. For the second generation, Cito scores and secondary school performance are low for Turkey, Morocco, Caribbean, (former) Netherlands Antilles, Suriname and much of Africa. High Cito scores and school performance are found among children from second-generation migration backgrounds in East Asia, Israel, Scandinavia, Switzerland and North America…

Greater ‘cultural distance’ correlates with lower chances of integration

It is possible to measure the ‘cultural distance’ between the Netherlands and the country of origin on the so-called ‘cultural values map’. This is a map based on the results of the World Values Survey, a large-scale and long-term survey of values and norms in a large number of countries. It turns out that this cultural distance is strongly negatively correlated with all kinds of integration indicators such as education level, Cito score and net contribution to the Dutch treasury. The further away the culture of a migrant group is from Dutch culture, the lower the score on net contribution and all kinds of other integration indicators. This also affects the second generation born, raised and educated in the Netherlands, with the group with the greatest cultural distance – the so-called African-Islamic cluster – having a net contribution almost two hundred thousand euros lower than one would expect based on education and the like [told you so].

Remigration opportunities: the welfare state acts as a ‘reverse welfare magnet’ [in Germany, the Berlin Blob considers this ‘NAZI’ stuff]

Differences in educational attainment and Cito scores between groups arise through historical coincidence and processes of (self)selection. Negative self-selection in remigration further exacerbates existing differences, because it is precisely groups with a low net contribution to the Dutch treasury and a large cultural distance to the Netherlands that tend to stay in the Netherlands for a long time. These are also the immigrants who score poorly on all kinds of integration indicators: low income, low education level and ditto Cito scores, high benefit dependence and crime rates, and so on. The Dutch welfare state thus acts as a ‘reverse welfare magnet’ that tends to ‘hold on’ to immigrants with a negative net contribution, while immigrants who score well on integration indicators often leave quickly…

Perspective

Immigrants that make on average a significantly negative contribution to Dutch public finances are mainly those who exercise the right to asylum, especially if they come from Africa and the Middle East. The latest UN population forecast shows that the total population in these areas will increase from 1.6 billion to 4.7 billion by the end of this century. It is not implausible that the immigration potential will at least keep pace. Immigration pressure, in particular on the welfare states in Northwest Europe, will therefore increase to an unprecedented degree. This raises the question of whether maintaining the open-ended arrangement enshrined in the existing legal framework is a realistic option under these circumstances.

The current cabinet recently indicated to the House of Representatives how it views the existing legal framework. This was in response to a report on an “investigation into the question of whether, and if so how, the 1951 Refugee Convention can be updated to provide a sustainable legal framework for the international asylum policy of the future”.

This response shows that the Dutch cabinet wants to maintain the existing legal framework for asylum immigration – despite the large-scale abuse identified by the cabinet. The calculations in this report leave no doubt about what this means in the long term: increasing pressure on public finances and ultimately the end of the welfare state as we know it today. A choice for the current legal framework is, therefore, implicitly a choice against the welfare state.

Bottom Lines

As much as I would like to keep on citing the report, please read it. It is thorough, quite objective, and offers quite a bit of policy wonkery for the relevant discussions.

I think that much of what Van de Beek et al. relate also applies to the laundry list of countries (North America, Oceania, the British Isles, Scandinavia, Belgium, Luxembourg, France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Spain, Israel, India, Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan). Yes, in all these places there will be similarities and differences once such granular data would be studied and evaluated.

Voters today must be informed about these issues, but I doubt that anyone in the Blob would like information like this report to get widely known.

Table.02 clearly breaks down the cost/benefit ratios, and no polity—or policy—can withstand these ‘harsh’ realities for long. Welfare states will likely cease to function well before we’re at the end of that particular line.

What is there to do? Can Something—Anything—be done?

I suppose that, as the relative power of the above-listed countries shrinks ever further, esp. in the UN, meaningful ‘reform’ cannot occur. Imagine the re-working or revocation of many of the UN’s fundamental conventions, ranging from refugees to asylum or the like. Ain’t gonna happen.

If these institutions cannot be ‘changed’ to preserve Western societies, then perhaps Western societies should consider leaving these institutions, if that’s what it’ll take to rid themselves of such conventions.

I suppose that the IHR, currently debated under the auspices of the WHO, are a test case. Imagine a Trump victory in November and an US exodus from the WHO, NATO, and perhaps even the UN. What a game-changer would that be?

On a national level, we need to work towards adjustments to these conventions, laws, and regulations that govern these things.

Moreover, there’s little doubt now that the further devolution of authority to transnational entities (esp. the EU) is a net-negative factor here.

We’ll see how things go, but if the recent uptick in ‘right-wing’ parties across the West is any indication, it looks like the electorates are ‘getting there’ well before gov’ts, legacy media, and the Blobs’ willing executioners.

Here's a problem that I always have with analyses of this type. Western countries have all sorts of labor needs that simply won't get done unless (a) they start paying significantly better or (b) labor from poorer countries is imported to do it. Now, (a) is always an option, but that translates into higher taxes or higher prices for the host population, which is why it's resisted. So, you get (b). And suddenly, the Moldovan girl changing grandma's diapers is a "fiscal sink." But in reality, *grandma* is the fiscal sink. Without the Moldovan girl, grandma would get to fester in you-know-what. So, you get the Moldovan girl to change grandma's diapers for shit pay (no pun intended), and then you explain to her at every turn that it would be so much better if she weren't there.

Of course, it may be that in the long run, it would be cheaper to just pay for grandma's diaper change more so that some of those PhDs whose skills the labor market has little use for would consider a career change and retrain in diaper changing (rather than becoming DEI coordinators for instance, which pays a lot better at the moment, though it's unclear to what use). Maybe. In the long run (when the Moldovan girl is no longer a girl, but a woman with kids who need to live somewhere and be educated somewhere). However, in the short run, the Moldovan girl is cheaper. Plus, the PhDs get to feel superior for her.

Data from Denmark show exactly the same results. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4698/10/2/29