In the Year 1 BC™ (before Covid), the German gov't spent 15b on 'NGOs'

In case you wondered why 'our democracy™' went badly off the rails in 2019/20, here's a sizeable share of the answer--plus a solution: reform voting rights

A few years ago, that is—before Covid—the German gov’t was spending in excess of 15 billion euros on ‘NGOs’. Or rather GONGOs, by which are meant ‘government-organized non-governmental organizations’ that are ‘set up or sponsored by a government in order to further its political interests and mimic the civic groups and civil society at home, or promote its international or geopolitical interests abroad’ (source).

The main issue I take here is that these funding sources aren’t declared, neither domestically nor abroad, and whatever one thinks about the ‘DOGE’ efforts in the US, it’ll probably take more than whatever Mr. Musk’s musketeers can achieve to clear out these Augean Stables on either side of the Atlantic.

Remember, before you get started, the below piece was penned before the Covid racket, hence if you’re still, at times, marvelling at just how it could be that everybody fell in line, well, look no further.

This is also my litmus test for the efforts of ‘DOGE’, by the way: these things, connections, and money flows cannot escape notice of these brainiacs.

Finally, this was done during the Merkel years, which, I submit, should not come as a surprise to anyone.

Translation, emphases, and [snark] mine.

The Good Opinion-Makers Who No-one Voted For

By Christina Brause and Anette Dowideit, Die Welt, 15 May 2019 [source; archived]

Oxfam, Umwelthilfe, Amadeu Antonio Foundation: NGOs have a social function. They are often perceived as positive, neutral, and enriching [by whom, pray tell?]. Yet many of them spread ideology. What many do not realise: taxpayers help pay for their work.

In the course of the 19th century, millions of people migrated from the countryside to the cities. Industrialisation was in full swing, and the many uneducated low-income earners who suddenly found themselves working in factories lived in flats or shacks that were far too small. Because they did not want to see this misery, citizens and church representatives joined forces in the cities and organised ‘care for the poor’: they looked after the sick, fed the people and looked after the children [as a history professor, I can assure you this kind of BS would get you a grade worse than F].

It was the birth of a new concept. Private individuals and churches took on tasks that should have been carried out by the state [this is even more false; I can only recommend Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation (1944) to the loons spreading, well, ideology here]: social welfare for the poor in the country [another piece I can recommend—that is, if you read German—is G.F. Knapp’s 1887 two-vol. treatise on the fate of these rural, landless poor: it was the social question of the 18th century, finally resolved via the abolition of serfdom—and that was done at the request of the property-owners so that they could get out of their pre-industrial (‘feudal’) obligation of helping their subjects in times of need; adding insult to injury, the property-owners often made the subjects pay for their freedom while refusing to take responsibility any longer]. The initiatives of that time were the forerunners of today’s welfare organisations such as Caritas [the Catholic version of the salvation army] or Arbeiterwohlfahrt [literally ‘working men’s welfare’], and they were the prototype of a political actor that today is considered the ‘fifth estate’ in the state: non-governmental organisations [with the main difference being, let’s not forget this here, that they were funded by donations and/or dues, i.e., unlike today’s NGOs, the gov’t wasn’t involved].

Today, things are different. NGOs, foundations, and associations are active in almost all areas of public life: they look after people in need of care or refugees, provide development aid, conduct research into the future viability of the country. They do this in the name of civil society [orig. Zivilgesellschaft, or civil society, which is another of these terms with which these people confuse Joe Sixpack], to which they refer. In this way, they influence political decisions—without having received a mandate to do so. And they are provided with taxpayers’ money [and this is the heart of these shenanigans, isn’t it?].

More Than 15 Billion Euros in Taxpayers’ Money

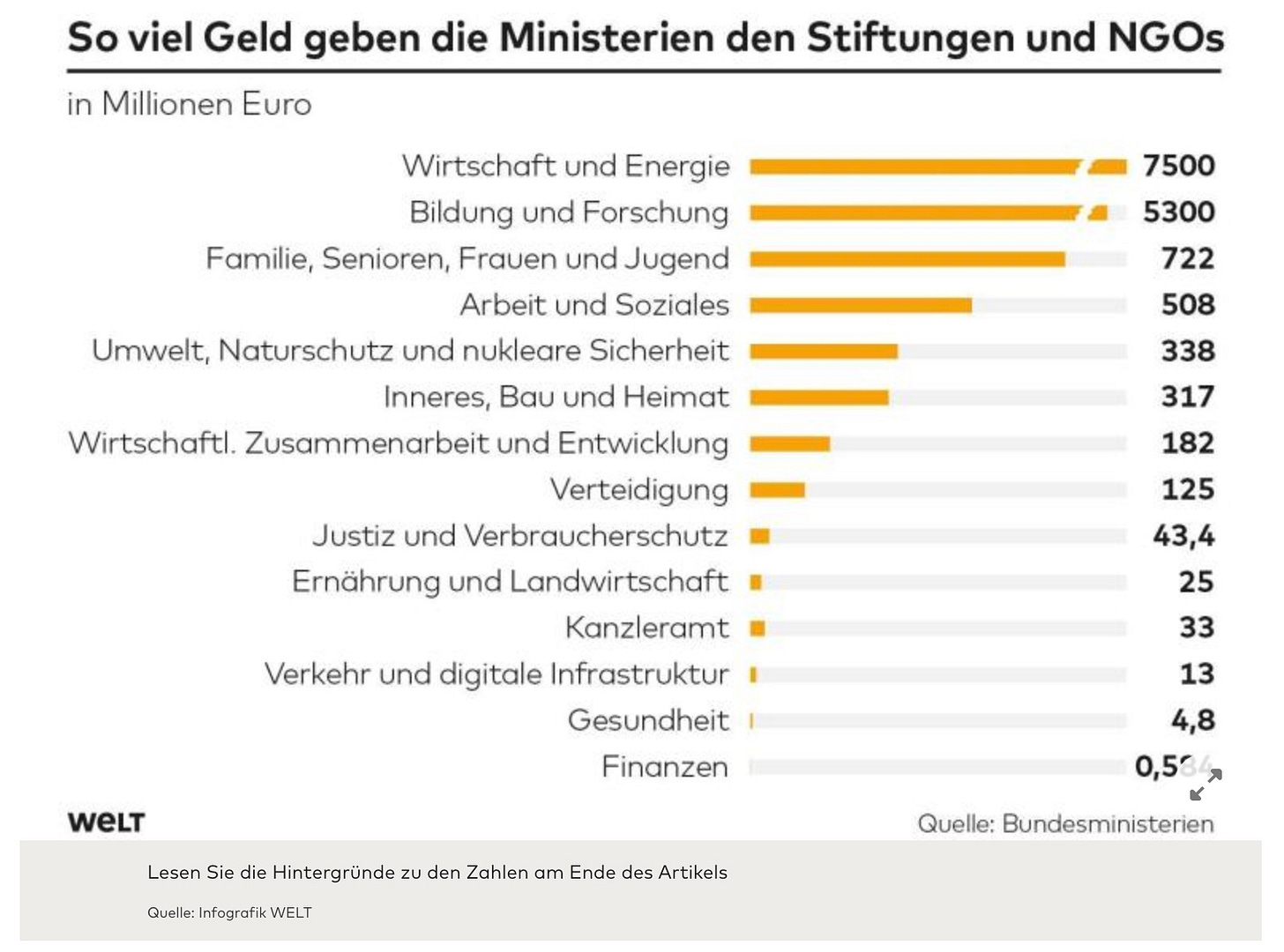

Germany spends money on the work of non-governmental organisations: Last year [fiscal year 2018], the federal government alone paid around 15.5 billion euros to associations, foundations, and NGOs, and in some cases also private companies, so that they could use the money to take on tasks that are in the public interest. This was the result of a survey conducted by Die Welt am Sonntag among the 14 federal ministries and the Chancellery.

However, it is difficult to ascertain which organisations receive these 15.5 billion euros and what exactly they do with the money [talk about ‘black’ budgets for the ‘national security community’, eh?]. On request, only some of the federal ministries provide an individual breakdown of how much money they paid to whom and for what in the past year [how dare you, unwashed rabble, to enquire what a notionally democratic, accountable gov’t of the people and for the people is actually doing in our names]. Some of them refused to give the names of funded institutions for data protection reasons, while others claimed that it would be too time-consuming to collect the data [let’s talk about incompetence here for a moment, shall we?].

So much money is spent by federal ministries on foundations and NGOs

Background to these data are found at the bottom of the article.

It is also difficult to gain an overview of the funding landscape because the ministries included different types of expenditure in the funding totals they provided on request. While the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), for example, only reported funding projects and also named these for individual non-governmental organisations, the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) also included projects carried out by private companies on behalf of the German government [talk about the gov’t mandating certain reporting and compliance regulations for private companies that the state doesn’t adhere to…].

In addition, both the BMWi and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) stated sums that also include institutional funding for institutions such as the German Aerospace Centre or the German National Tourist Board.

However, the funding tables of individual ministries show that there is multi-million euro institutional funding for entire organisations and contracts for institutes commissioned by the federal government to investigate specific research issues. There are individual projects that receive funding and projects by project groups that receive funding [are you surprised yet?].

Even Politicians Find it Difficult to See Through

Even members of the Bundestag find it difficult to get an overview [read this once more: gov’t agencies refuse to disclose these data to the oversight bodies: that’s both unconstitutional and—treasonous]. A few of them, for example from the FDP and the Left Party, are currently trying to force the Federal Government to provide information. They are writing small enquiries [kleine Anfragen] on the funding amounts for individual organisations, to which the federal government must respond. The fact that even this is not always successful is shown by the recent answer to a question from FDP MP Christoph Meyer. He had asked which projects of charitable organisations the federal government had funded in recent years. In response, he received a list of around 40 pages—on which the names of the individual funded projects were listed, but not the sums paid for them.

It is also difficult for outsiders to understand how the ministries decide which projects receive funding, which organisations are allocated which sums, and whether organisations are more likely to receive taxpayers’ money if they are close to the parties that are currently in charge of the respective ministry. Sometimes former employees of NGOs sit in the ministries or vice versa, as is the case with NABU [Naturschutzbund, an environmentalist ‘NGO’]—its former head Jochen Flasbarth is now State Secretary in the Federal Ministry for the Environment [again, this is data from 2018 from the Merkel years: all of these shenanigans got way, way worse thereafter].

Some of the subsidised institutions represent certain ideologies or pursue goals that are not necessarily in the public interest. Example: the German environmental organisation Deutsche Umwelthilfe (DUH). The organisation obtained driving bans for diesel vehicles in several cities through court rulings due to excessive particulate matter pollution. It declared that it was enforcing the law and representing the concerns of civil society against the industry.

But ‘freedom’ is just as much a concern of civil society as ‘environmental protection’. That is why there was criticism. In December, North Rhine-Westphalia's Minister President Armin Laschet (CDU) [he who once was considered Merkel’s successor, but he lost the 2021 federal election] labelled the DUH a ‘warning association’ [orig. Abmahnverein] that was ‘co-financed by a foreign car company’. In fact, its work in recent years has not only been co-financed by taxpayers, but also by Toyota—and therefore a competitor of the German car industry. Toyota benefits from driving bans [who would’ve thought, eh?].

Among the influential non-governmental organisations in the country are also big names that explicitly renounce state funding: the classic campaigning NGOs such as Greenpeace [receives funding from big donors, billionaires, etc.], Peta, and Foodwatch are among them, as are business-oriented opinion leaders such as the New Social Market Economy Initiative [Initiative Neue Soziale Marktwirtschaft] and the Bertelsmann Foundation [also owns tons of legacy media outlets]. Others, however, who represent equally strong ideologies, accept taxpayers' money: Oxfam, for example, the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, or the Association of Expellees [Bund der Vertriebenen].

This is how politics is shaped at taxpayers’ expense. For example, by producing research results on behalf of a ministry—like the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research—which critics claim could be ideologically biased. Or, like Oxfam, by introducing study results into the political discourse whose methodology is questioned by economic researchers and which also provoke criticism among politicians—such as the FDP parliamentary group in the Bundestag this year.

Does Germany also need a lobby register for NGOs?

Fuelled by the case of Deutsche Umwelthilfe, a debate has flared up again in the Bundestag: shouldn’t more transparency be created in the non-governmental organisation sector by creating a binding lobby register—in which NGOs, associations, and foundations would then also have to disclose their income and how it is used, alongside traditional business lobbyists? [that’s a no-brainer, if you’d ask me]. The Green and Left parliamentary groups in the Bundestag have been campaigning for this for years, while the majority of the CDU/CSU has so far been against it, fearing that the effort required for such a register would not be offset by sufficient knowledge gain [read that again: the people would gain knowledge, but the leaders would be embarrassed].

Twelve associations, their work and the amount of their subsidies are described below [I’m not translating all these examples]. The aim of the selection was to provide examples of the funding policy, how it is handled, and the conflicts that arise as a result. It was based on interviews with politicians from various parties, political researchers and the heads of many NGOs.

These are organisations that receive particularly large amounts of money or those that have been controversial in the recent past: these include Caritas and consumer advice centres, which take on public tasks on behalf of the German government and have thus established themselves as political powers; ideologically driven organisations, such as Deutsche Umwelthilfe, Oxfam and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, which use public funding to make policy or significantly influence it.

Nabu and BUND

Naturschutzbund Deutschland (Nabu) and Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz (BUND) [two environmentalist lobby groups] see themselves as advocates for the environment. For example, they are fighting for an ‘agricultural turnaround’, for organic farming, and a coal phase-out. They organise petitions to protect bees, demonstrations against the clearing of the Hambach forest [where open-pit coal mining was proposed; Gretha Thunberg is also a frequent ‘guest’ at such events], and participatory campaigns to avoid plastic waste. They do a lot of lobbying at federal level—currently for the faster implementation of the EU directive on better water protection, for example.

Nabu and BUND regularly sit on federal government advisory committees and contribute to political decisions: one example is the controversial ‘Gesamtkonzept Elbe’, which the government adopted in 2017. BUND, Nabu, and other environmental organisations succeeded in ensuring that the federal government’s guidelines now state. The river may only be made more usable for shipping if it is ensured that the floodplain landscape between the Czech border and Geesthacht in Schleswig-Holstein is not further damaged as a result.

Politically, the environmental NGOs are closely linked to the Greens and often bring their demands into politics through them. Before the exploratory talks to form the current federal government, for example, the leaders of the Greens’ parliamentary group sat down with Nabu President Olaf Tschimke and the head of BUND, Hubert Weiger, to determine the Greens’ priorities for the current legislative period, as can even be read on the Greens’ website.

However, there are also connections to politics and the federal government at a personal level: former officials of the associations sit in the ministries that commission the foundations with projects [it’s a key feature of the revolving door]—who decide on the awarding of contracts to the organisations and can bring them into decision-making bodies.

The best-known example is Jochen Flasbarth, former Nabu President and now State Secretary in the Federal Ministry for the Environment. Flasbarth was appointed to the ministry in 2003 under the red-green federal government. He is considered an advocate of the energy transition and has been criticised by the German Farmers’ Association for acting against the interests of farmers—most recently in March [2019], when the ministry announced that the current fertiliser ordinance would be tightened.

Funding

While Greenpeace, the largest NGO in the field of environmental protection, does without taxpayers’ money completely, Nabu and BUND are supported with money from the federal budget. Last year, Nabu alone received 5.15 million euros from the federal government, more than one in ten euros of its budget. According to an answer to a small enquiry from the FDP parliamentary group in 2018, the largest share came from the Federal Ministry for the Environment for projects such as a ‘feasibility study to determine the added value of the population for different types of forest’ [we all need DOGE-style transparency].

Since 2006, the ministry has also paid Nabu representatives travel expenses to accompany politicians on delegation trips—such as the then SPD Federal Environment Minister Sigmar Gabriel to Brazil. BUND received a total of 1.5 million euros from the federal budget last year [2018], including 166,000 euros for ‘strengthening civil society in the implementation of national climate policy’.

Society for Security Policy

The Gesellschaft für Sicherheitspolitik (GSP) is an educational and lobbying organisation. Among other things, it organises discussion evenings and lectures on defence and security policy, which take place in 80 sections throughout Germany. Speakers are often Bundeswehr officers and conservative politicians, with topics such as political dealings with Russia or NATO being discussed.

Politically, it is closest to the CDU/CSU, although its current president Ulrike Merten, former chairwoman of the defence committee in the Bundestag, belongs to the SPD [see, it’s ‘bipartisan’ in Germany, too]. The GSP maintains links to the Bundeswehr and the arms industry: its board of directors includes former officers of the Bundeswehr, and its board of trustees includes, for example, a representative of the German Society for Defence Technology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Wehrtechnik, DWT), which in turn is co-financed by arms companies such as Heckler & Koch and Diehl Defense. The GSP emphasises that it does not receive any money from the defence industry itself [nope, it’s ‘laundered’ via intermediaries to enable ‘plausible deniability’, on which see below].

Funding

The Press and Information Office of the Federal Government provides the GSP with around three quarters of its budget, which according to the office was around 400,000 euros last year. The information from the Press and Information Office also shows that the annual funding from taxpayers’ money has been continuously increased since 2010 under the CDU government—it is now twice as high [imagine that kind of return on investment on, say, your retirement investments…]. This has been criticised by the Left Party parliamentary group in the Bundestag: it is obvious that the organisation represents the political interests of the Bundeswehr and the CDU/CSU.

Amadeu Antonio Foundation

According to the foundation, which was established in 1998, its work centres on combating right-wing extremism, racism and anti-Semitism [I’ve written about that one at-length before: it’s Germany’s premier ‘rat-out-thy-neighbour’ institution, provided your neighbour is a ‘right-winger™’]. The start-up capital came from Karl Konrad Graf von der Groeben, who came from East Prussia and had contact with the 20th July resistance. The Amadeu Antonio Foundation (AAS) is named after a labourer from Angola who was beaten to death by right-wing extremist youths in Eberswalde, Brandenburg, in 1990. Since its beginnings, it has supported more than 1,350 projects. The foundation has been repeatedly criticised for some of these projects.

One example is ‘no-nazi.net’, an internet project designed to sensitise young people to radical right-wing and extreme right-wing tendencies through texts, videos, graphics and quizzes. From 2011 to 2018, the project and the follow-up project ‘Debate—for digital democratic culture’ were funded by the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs with a total of more than one million euros. The CDU also appeared in a list of the ‘New Right’ on the website. The then CDU Secretary General Peter Tauber accused the foundation of equating his party with neo-Nazis and right-wing populists. The AAS defended itself: four people were listed who were still or had previously been members of the CDU. The wiki was taken offline in August 2016.

Last year [2018], the foundation was criticised for a brochure that it had produced together with the Ministry of Family Affairs. It was intended to give daycare centre teachers tips on how to deal with right-wing extremist families. The salutation was written by Family Minister Franziska Giffey (SPD).

The brochure states, among other things, that children of ethnic [orig. völkisch] parents are reserved, talk little about home, and seem to behave particularly well. They can be recognised by the fact that girls wear dresses and plaits and are taught housework and handicrafts. Boys were drilled particularly hard physically. The brochure called for cases of right-wing extremist parents to be publicised in kindergartens. The deputy leader of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group, Nadine Schön, described the brochure as a ‘state instruction manual for parental espionage’ [we have the wonderful term Blockwartmentalität for this in German—it refers to people who like to rat out their neighbours; the contrast to, say, mandatory ‘gender-affirmation’ is even too blatantly obvious not to note].

The director and founder of the foundation, Anetta Kahane, had also been criticised before. In 2015, Heiko Maas (SPD), then Minister of Justice, invited her to join a working group, a so-called task force on dealing with hate messages on the internet. This was criticised by Hubertus Knabe, then director of the Hohenschönhausen Memorial, among others, because it had already become known in 2002 that Kahane had been recruited by the Stasi as an unofficial collaborator (IM, or inoffizielle Mitarbeiterin) at the age of 19 and had worked as such for eight years. According to Kahane herself, she then ended her work and applied to leave the country [Ms. Kahane spied on her neighbours for eight years, which is apparently enough to cause her conscience to revolt (/sarcasm); see ‘more’ about Ms. Kahane here].

In 2015, the foundation also published a brochure on the topic of hate speech, which critics, particularly on social networks, accused of censoring opinions on the internet through its recommendations for action [care to guess who’s ‘bad™’ in this brochure?].

Funding

In 2017, the foundation had 3.2 million euros at its disposal, of which 945,000 euros came from the federal government. In 2018, it had a total of 4.3 million euros, of which 1.1 million euros came from the federal government. For 2019, the AAS was again approved for 1.1 million euros in federal funding. In total, the foundation is expecting a budget of around 3.5 million euros this year.

Aktion Deutschland Hilft

Aktion Deutschland Hilft collects donations for victims of natural disasters or violent conflicts under the motto ‘Helping faster together’. The NGO was founded in 2001 as an alliance of several German aid organisations. These include Arbeiterwohlfahrt, Paritätische Wohlfahrtsverband and Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe.

The organisation is particularly well known for its media-effective appeals for donations. The alliance collected a total of more than 130 million euros for the victims of the devastating tsunami in South East Asia in 2004, in which around 230,000 people died. According to its own information, this is the largest sum that the alliance has collected since it was founded [we know relatively little how they spent these 130m euros…they claim to have financed ‘4,000 helpers’ who ‘helped 1.9m people’]

The alliance maintains close links to politics. Its patron is former German President Horst Köhler (CDU). Foreign Minister Heiko Maas (SPD) is Chairman of the Board of Trustees, previously headed by Frank-Walter Steinmeier (SPD) [current federal president] and Sigmar Gabriel (SPD) [vice chancellor under Ms. Merkel]. The current Deputy Chairman is Michael Brand (CDU), a member of the Bundestag, who was Chairman of the Committee on Human Rights and Humanitarian Aid until 2017 and is still a member.

Manuela Roßbach, Managing Director of Aktion Deutschland Hilft, has already been heard by the committee as an expert. She recommended that politicians invest more in the training and further education of humanitarian aid workers. She stated that Aktion Deutschland Hilft already organises training courses for ‘external colleagues’.

Contact with politicians is not limited to the committee. According to Roßbach, the organisation regularly exchanges information with high-ranking ministry representatives. ‘However, we decide which projects we initiate independently of this.’ For example, the alliance has supplied refugees in the Balkans. Of the budget approved for this, 100,000 euros remained. This was donated to SOS Mediterranee, the NGO that saved around 30,000 refugees from drowning in the Mediterranean with the ‘Aquarius’.

Financing

The Alliance is financed by donations, fines, occasional bequests, and membership fees from the Alliance organisations. In 2018, the total budget was 36.16 million euros. Aktion Deutschland Hilft received state funding from the Federal Foreign Office. From 2015 to 2018, the ministry funded two projects totalling 430,000 euros.

The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research

The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) researches climate change and everything to do with it—often on behalf of the German government: pollutant emissions, effects on ecosystems, climate migration. According to its own description, PIK’s task is to create a ‘robust basis for policy decisions’ through its research. According to a ranking by the University of Pennsylvania, it is currently the most successful environmental policy think tank in the world.

The Institute’s greatest political success was to establish the two-degree limit for global warming as a political goal. The founder and initiator of the Institute, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, is regarded as the spiritual father of this limit. He was Chairman of the German Advisory Council on Global Change in 1996 and recommended the two-degree limit to the German government and the EU Commission. At the time, the EU defined it as a political target. At the 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference, all 195 member states made a binding commitment to this target [I wrote about the PIK’s director, Stefan Rahmstorf, last year: it’s incredible, if you would believe it].

Schellnhuber and the current PIK Director Johan Rockström have been repeatedly criticised for blurring the boundaries between research and political activism with political demands [who would’ve thought that…]. In 2013, the Federal Ministry of Economics under Philipp Rösler (FDP) opposed a second term of office for Schellnhuber as Chairman of the Federal Government’s Scientific Advisory Council because, in the ministry’s view, he was too quick and radical in his call for a world beyond fossil fuels.

Another well-known climate researcher, Hans von Storch, criticised in an interview with Wirtschaftswoche in 2010 that Schellnhuber often interfered in day-to-day politics with concrete demands and called on the German government to ‘consider whether this kind of interference is what it pays scientists for’ [15 years ago, one could still say that quiet part out loud…]

At the Green Party's national delegates’ conference in November 2017, Schellnhuber called for a right of asylum for global victims of climate change from the countries that caused it. Rockström recently went out on a political limb at the end of April [2019] with a call for a climate rescue diet. In an interview in the Tagesspiegel newspaper, he called for citizens to be allowed only 100 grams of red meat per person per week, as meat production was damaging the planet. In March, Rockström invited the Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg to his home and discussed ‘possible solutions to climate change’ with her in private, according to the PIK.

Funding

According to the German government, PIK received a total of around 146 million euros from the Federal Ministry for the Environment and the Federal Ministry of Research between 2000 and 2018 [that institution would literally cease to exist if it wasn’t for the German gov’t]. The government commissioned the institute to prepare expert reports on several occasions. In 2018, for example, around 340,000 euros went towards a PIK study on ‘Approaches to understanding the causes and effects of past, present and future climate change based on the theory of complex systems’.

[I’m skipping a few more of these case studies as the piece is very long already: what a difference a few years make in terms of long-form journalism, isn’t it? Also, do note that one of the co-authors of this piece, Anette Dowideit, is the editor-in-chief of Correctiv, one of the more infamous gov’t-funded ‘outlets’ that is behind ‘Stupid Watergate’.]

The Data From the Ministries

The Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), the Ministry of Finance (BMF), the Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection (BMJV), the Ministry of Health (BMG), the Federal Chancellery (BKAmt), the Ministry of Transport (BMVI) and the Ministry of Defense (BMVg) sent a complete breakdown of all funding projects from associations, foundations and NGOs and the specific recipients upon request.

The Ministry of Family Affairs (BMFSFJ) responded in less detail, breaking down the funds received by funding groups - on the grounds that listing all project funding would be too time-consuming.

The Ministry of Labor (BMAS), the Ministry of Economic Affairs (BMWi), the Ministry of Research (BMBF), the Ministry of the Interior (BMI), the Ministry of the Environment (BMU) and the Ministry of Agriculture (BMEL) only provided information on the total amount of their funding projects. While the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Labor cited data protection, the five other ministries stated that a breakdown would be too labor-intensive and therefore not feasible within weeks.

The Federal Foreign Office (AA) was the least willing to provide information: even after repeated inquiries, they stated that they could not provide the funding amounts for 2018 because they did not yet have an overview themselves. For 2017, the AA could only provide the total amount as ‘a mid-three-digit million amount’.

Bottom Lines

We knew so much more ‘BC™’ (before Covid) than we do know, isn’t it.

None of the above was a secret; these days, it’s all evil loony conspiracy monger territory.

Speaking of the messengers for a moment, let’s consider the fact that the above piece was co-authored by Anette Dowideit before she moved over to Correctiv, that gov’t-funded spreader of disinformation.

None of these fundamentals have changed for the better in Europe.

Just look at the absurd bruahahahaa of the EU’s chicken hawks who wish to continue fighting Russia, ‘in spite’ of Mr. Zelenskyy’s breakdown.

It’s an embarrassment, esp. as most of these morons don’t have sons who’d do the dying.

How do we change these dynamics?

I propose separation of active (you can cast your vote) and passive voting rights (you can run for office): restore or institute conscription/national service for men and train many of them for 6-8 months; that’s enough for deterrence and too little for offensive warfare (plus one retains the option of quickly mobilising the militia for natural or man-made disaster relief).

If you’ve done such service, you get passive voting rights.

What about women, you ask? Well, both men and women shall have active voting rights upon reaching 18 or 21, and much like men who complete national service, women shall receive passive voting rights in exchange for motherhood.

In case you yell abusive stuff my way, feel free—but the above isn’t even my idea: it was discussed in 1918 in Switzerland, but in the end, the right to vote was given to women in exchange for—nothing; men still get conscripted (which was the original justification of elites to grant voting rights to the lower rungs in the first place).

Is such a proposal ‘fair’? That’s the wrong question.

Would it make sense?

I think so: most men could do with a bit of discipline around age 20, to be honest, and nothing imbues a sense of shared destiny as disliking the master-sergeant (I did 8 months of military service).

The same goes for motherhood: nothing says ‘I’ve got skin in the game’ better than having children. If you think I’m way off, just look at the craziest female politicos™—odds are, they are single/childless women (that doesn’t mean men can’t be loons, but it’s about the skin in the game part).

So, how to restore a sense of shared destiny? Make voting more of something one has to earn, esp. if we’re talking running for office.

Would that create a two-tier society?

Nope, that already exists (just look at those who are ‘net taxpayers’ vs. those who are ‘net recipients’).

In my view, doing so would go a long way of restoring sanity and, yes, accountability.

It wouldn’t be the silver bullet, but it would take us a few steps away from the brink, esp. if combined with reduced immigration and a stop of naturalisation.

Layer upon layer upon layer… lots to peel back in most of our countries and yes going further back in time too.

And I agree with you that fairness can be a red herring vs what is needed. I like your skin in the game.