Covid in Norway: as 4th jabs are rolled out, public health officialdom fears 'vaccine fatigue' as 1 out of 1,250 triple-jabbed require hospitalisation in July

Highlights incl. hospitalisation incidence isn't affected by vaxx status--and there were 10 X more hospitalised vaccinees vs. unvaccinated in July 2022: is the gov't out there to 'get us'?

It’s been quite a while since my last dedicated post about all matters Covid-19 in Norway. This is mainly due to the increased efforts that the people over at the Institute of Public Health (IPH) put into making their website user-unfriendly: as mentioned in spring, there’s no more weekly updates (these now come biweekly), and they no longer provide information about the ‘injection differentials’ (i.e., differences between unvaccinated vs. ‘all-cause vaccinated’).

Please find my last dedicated postings here:

Fourth Jab now Available for People Aged 65-74

According to a news item published on 5 August, ‘it is particularly important that those 75 and older, as well as people in hospitals take a fourth dose of the Covid vaccine now’. The aim, the IPH informs the public, is to quickly ‘vaccinate’ everyone in this age bracket and then move on to vaccinate those aged 65-74’, according to deputy director Geir Bukholm.

I’ll spare you the boilerplate ‘reasoning’ (ahem) that the IPH staff provides, but I will take you through the ‘updated risk assessment for another booster shot (dose 4)’ linked on that same page.

Dated 28 July 2022, it’s the IPH’s official reply to ‘task 68 (2022)’ related to the Covid injection program.

The answer comes in two parts, with the first part (dated 24 June) seeing the IPH recommending a fourth shot for those 75 and older, a cohort of some 450,000 people. We also learn that the cohort from 65-74, as well as those 18 and older with pre-existing, or underlying illnesses, shall be able to get another round of these injections from 1 Sept. 2022 onwards. The latest date envisioned in their answers, 1 Oct. 2022, was chosen specifically ‘to be able to offer variant-specific vaccines’, but that also means that many Norwegians who received their third jab about half a year ago are now, well, not very much protected anymore (p. 2).

That is, if they ever were.

As a review of an assessment from spring 2022 suggests, ‘vaccine efficacy’ (VE) vs. Omicron was as low as 53% for the 20 days after the second dose. VE appears to be gone thereafter, but that didn’t—and still doesn’t—make public health officialdom abandon a clearly failed strategy, as the above-cited document shows.

Groundhog Day meets Clown World

In its current assessment, the IPH holds that the fourth dose will now be offered to ‘vaccinate those aged 65-74, as well as younger people at elevated risk…as fast as possible’, but to do so ‘before any such offer goes to everyone else’ (emphasis in the original). If a municipality is done injecting everyone in these cohorts, they may offer the remaining doses to the rest of the population (p. 4).

In its assessment (pp. 5-7), however, the IPH tells us many interesting things, including the fact that the summer wave (of BA.5) is cresting, which has resulted in more elderly people (75+) requiring medical attention, but ‘there is continued uncertainty about the size of a possible autumn wave with BA.5’.

A new wave of BA.5 could lead to a small increase in new hospitalisations in the 65-74 age group, but experience during the summer suggests that it will not be large as those vaccinated with 3 doses have been well protected throughout the summer. On the other hand, for this group in September, another two months will have passed since the previous vaccination (in December and January). For those who have not been infected since then, the protection against infection will have dropped significantly and the protection against hospitalisation may be somewhat reduced (my emphases).

You see, the problem faced by public health officialdom isn’t this (summer wave) or that (the actual efficacy of the injections), but spelled out a bit below:

Offering another dose now will have an impact on when the next dose can be given in the autumn. There should be an interval of at least 4 months between the vaccine doses, which means that an autumn dose with any variant-adapted vaccine cannot be given until the turn of the year if a new booster dose is given now in August/September to the current target group. Since such a variant-adapted vaccine can arrive as early as September, and can provide better protection against a possible larger autumn/winter wave, this is a potential disadvantage. In addition, one should be aware of the risk of general vaccine fatigue [vaksinetretthet] in the target group when recommending repeated doses, which could affect support for both a new dose of the Covid vaccine and this season’s flu vaccine.

Oh, ‘vaccine fatigue’, you say? Is this a new word of saying ‘vaccine hesitancy’ without doing so? I mean, why on God’s green earth would anyone who’s taken three of these jabs already and got infected anyways line up for another shot of these injectable products?

Here, the IPH—inadvertedly, I’d argue—gave away their main concern: that people would somehow begin to question the wisdom of repeat injection with a product that, as the quote above also shows, offers little in terms of ‘protection against infection’.

The most laughable part is on p. 6, though, and it contrasts the IPH’s two avenues:

Option A: offer a fourth jab as soon as possible, which ‘offers better protection against a possible summer wave’ (which, as mentioned above, the IPH says is cresting now), but offers ‘les protection against an expected winter wave due to the time elapsed since injection’. Yet, ‘one can offer a fifth dose in December/January’, but doing so would still ‘carry the risk of overall vaccine fatigue [vaksinetretthet], which would affect both the Covid and Influenza vaccines’.

You see, the problem as the IPH sees it: this is a one-trick show, for if asked, the IPH would always say ‘vaccinate’, if that were possible. Problem is, though, that ‘one cannot give a variant-specific vaccine now, or this season’s flu shot, for they aren’t available yet’.

Yet, the IPH’s biggest worry here is that a national campaign for both injections is tricky as ‘the various target groups are offered these [injectable products] at different points in time’.

Option B: giving a fourth jab in October ‘offers better protection against the expected winter wave’. If done with an updated ‘variant-specific vaccine, doing so may offer better protection, but there is uncertainty how much better these variant-specific are [relative to the currently available jabs]’. Finally, this looks like the winner, because doing so ‘simplifies the task in many municipalities as they can at the same time vaccinate the same persons against influenza and have joint information campaigns’. It’s a win-win-win situation, as it renders life less complicated for public health officialdom, makes it cheaper to sell these products to the people, and is ‘thought to contribute to increased uptake for both vaccines’.

Tough choices, eh?

Bottom line for the IPH (p. 7; my emphases):

It is therefore important to ensure that those over 75 have been offered a second booster dose before the offer is made to the younger age groups. The same applies to the importance of prioritising vaccination of people who have not yet been vaccinated or people in the risk groups who have not received their first booster dose.

So far, so expectable.

What about the data to back up these aims?

Well, in that regard, there’s not really much to see, or rather: show.

As mentioned over the spring, Norwegian public health officialdom won’t disclose the injection differentials anymore, hence it’s hard to assess the above claims (conclusions) in light of any publicly available evidence.

Here, on p. 7, the following is claimed:

In the last four weeks, the median age among newly admitted patients has been 77 years (lower-upper quartile: 69-84 years), but it has varied somewhat depending on vaccination status: unvaccinated: 71 years (34-84 years; n=99), one or two doses: 76.5 years (54.5 – 84 years; n=104), three doses: 77 years (71 – 84 years; n=780), and four doses: 74 years (63.5 – 81.5 years; n = 104).

So, this is about as good as it gets in terms of glimpses into these injection differentials. At first sight, it looks like being unvaccinated carries a higher risk of hospitalisation for esp. younger age brackets (34-84), but take another look:

No. of unvaccinated requiring hospitalisation in July = 99

No. of hospitalised with any number of injections in July = 988

That’s an order of magnitude in terms of difference.

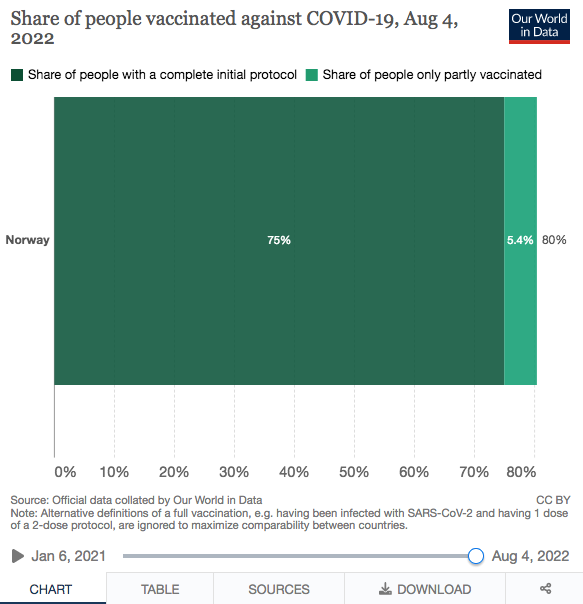

Yet, according to OWID, 75% of Norwegians have received two or more doses, with another 5% who remained ‘partly vaccinated’:

So, 4 out of 5 Norwegians have taken any number (1-4) of Covid injections. In other words: there’s four times as many Norwegians and foreign nationals residing there who are ‘vaccinated’—but somehow, the vaccinated make up 10 times the number of hospitalisations relative to ‘the unvaccinated’.

Yet, please look specifically at the (1st) booster recipients. According to the IPH’s dedicated website, their number stood at 2,979,831 as of 5 August 2022. Nine out of ten (92.7%) Norwegians who are 65 or older have received a third jab, and most of them did so in late 2021 and early 2022 (the red bars in the below graph):

As of 5 Aug., these age brackets (65 and older) comprised were 484,546 women and 432,871 men, or 917,417 individuals—which means that roughly 1 in every 1,250 of them required hospitalisation in July 2022.

You know, I could possibly explain why these cohorts might exhibit ‘vaccine fatigue’. Hey, IPH, why don’t you give me a call to help you out on this one?

One other gem to be found in the brief update is this statement (on p. 7; my emphasis):

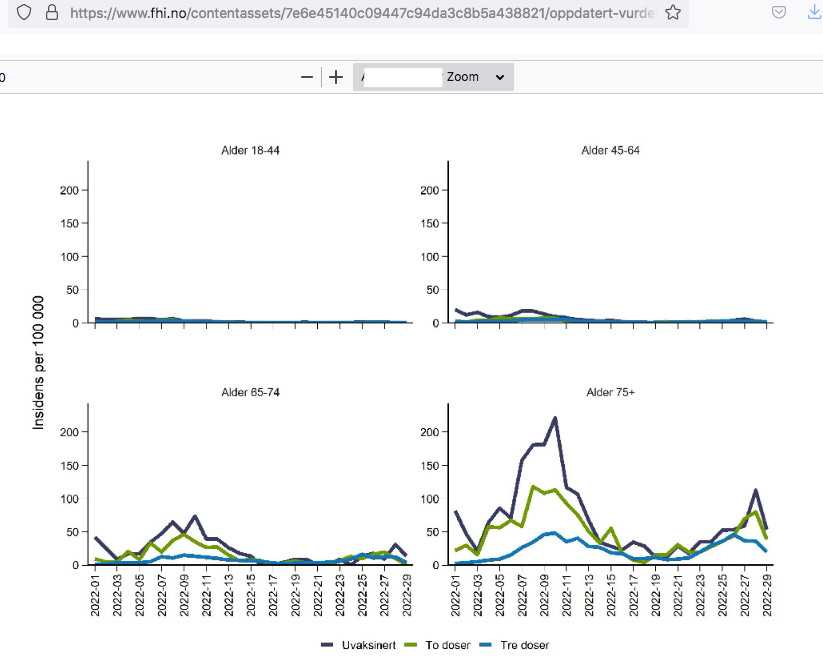

Figure 1 shows the development of the combined weekly incidence of hospitalisations with Covid-19 as the main cause and Covid-19-associated deaths for people 18 years and older. The incidence has been low in the age groups from 18 to 74 years, regardless of vaccination status.

Here’s Fig. 1: squeeze your eyes to see the injection differentials for those younger than 65:

Bottom Lines

If you’re not injected against Covid-19, you’re probably quite o.k. to remain so, according to official Norwegian data (whatever that may be worth).

It certainly looks a whole lot safer to do so, at least to me, in particular as infection, transmission, and the burden of illness is, in the IPH’s own words, ‘regardless of vaccination status’.

The hospitalisation rate for those who took any number of these injections is an order of magnitude higher than for those who remained unvaccinated—despite (because) the latter being far less numerous.

With regard to the first booster dose, the situation is even more obvious: while uptake stands at approx. 55% of the general population, the triple-jabbed made up about 79% of all hospitalisations for Covid-19 as main cause during July 2022.

Here’s some free life advice for both those triple-jabbed and the IPH: if you’re in a hole, stop digging.

That is, provided you’d like to climb out, eventually.

Yet, question is—do the triple-jabbed actually want to get out of the hole?

And, as a follow-up: does the IPH want the triple-jabbed to get out of the hole?

is the gov't out there to 'get us'?

DA!

so the heirs of the vikings, in former days the scourge of europe, have become a herd of docile sheep.

with the government openly discussing on how to lead them to the slaughterhouse....