Climate 'Activism' is 'Science™'

Meet our Nemesis: collectivists of all stripes unite to distract us from their wet totalitarian dreams

Today, we’ll take a look at the netherworld of the prophets of doom.

As many readers know, in recent years, the agit-prop about what once was a ‘theory’ (greenhouse effect) has morphed ‘climatic change’ to ‘global warming’ and ‘climate change’.

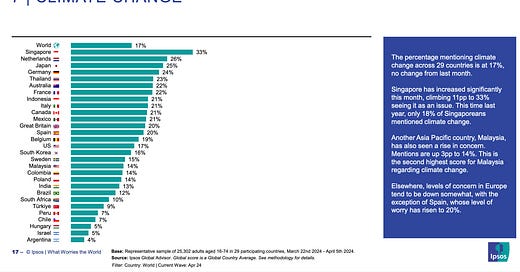

The fear in Central Europe is particularly is palpable, as evidenced by the a ‘country comparison’ of this item carried out by Ipsos globally last month:

What then, drives this madness in Europe? To that effect, we’ll take a deep dive into what kind of articles legacy media is pushing next.

As always, if non-English texts appear in translation, this is my work, as are the emphases added.

‘Collapsologists’ Predict the End of Civilisation

By Niklas Treppner, incorporating material from dpa, 6 May 2024 [source]

Is the end of our civilisation near? The collapsology movement has found its answer; this school of thought firmly believes that the fight against the climate crisis [last year, this term replaced ‘climate change’ as the standard moniker, of course, to increase awareness] will fail and the ecosystem will collapse, with much suffering and many deaths. Nevertheless, it [really?] does not want to give up.

The end of civilisation is discussed every fortnight—online in the ‘Climate Collapse Café’ [what’s the ‘carbon footprint’ of these meetings?]. ‘The speed at which the destruction of living nature and habitats is progressing leaves no other conclusion. It’s simply logical, it’s inevitable’, says Sibylle Eimermann-Gentil, who regularly takes part in the online meetings [leaving aside the real problem of habitat destruction, the jump from ‘logic’ to ‘inevitability’ is odd].

She is part of the collapsology movement, a school of thought that became particularly well known thanks to the French agronomist Pablo Servigne [see his French Wikipedia profile; in short, he’s an ‘immediate doom’ preacher envisioning the end of industrial civilisation ‘until 2030’; more on him below]. Together with eco-consultant Raphaël Stevens, he wrote the book Comment tout peut s’effondre [trans. How Everything Can Collapse, 2015; it is said to have inspired ‘Extinction Rebellion’]. Servigne firmly believes that efforts to combat the climate crisis will fail, the ecosystem will collapse, and human civilisation will end [this is not what his Wiki profile says: he muses about what may follow thereafter].

‘The collapse of civilisation is the most likely scenario’

Supporters in Germany also predict that human livelihoods will deteriorate dramatically worldwide as a result of ecological crises [‘you will own nothing, and you’ll be happy’]. Servigne expects a lot of suffering and many deaths, emphasises the founder of the ‘Climate Collapse Café’, Norbert Prinz:

The collapse of civilisation is the most likely scenario. There is no indication that we will really change anything.

The online café is intended to offer like-minded people a space to exchange ideas. Participants talk about their feelings, possible preparations for the collapse and life afterwards. The followers do not believe that humanity will die out completely. They believe that collapsed supply chains, ecological and economic systems will lead to the remaining survivors having to fend for themselves in small groups [sounds pretty much Hobbesian, but with a sick twist: since the dawn of human agricultural civilisations, humans have worked together to avoid this kind of ‘Mad Max’ situation: why would that be different in/after 2030?].

Science or Intuition?

The ‘collapsologists’ refer to science [rather: ‘the Science™’], cite reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and deliberately give themselves a scientific-sounding name. However, the representatives in Germany do not claim to be able to prove their forecasts scientifically. Prinz adds:

The topic is so complex that it cannot be researched scientifically and we should rely on intuition again [oh my, scientism is the more proper word].

There are hardly any studies on such an all-encompassing topic as the collapse of human society. Jobst Heitzig, mathematician at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research [which is to say, the institution headed by Professor Stefan Rahmstorff, a leading protagonist in the ‘scientistic™’ camp], is not surprised by this:

In principle, it is impossible to say with any certainty how likely a collapse of civilisation is. But you can develop scenarios of how it could happen [this is incredibly stupid on many levels: first, note Professor Joseph Tainter’s marvellous The Collapse of Complex Civilizations, which came out in 1989; note that Joe (we met twice, professionally) is very much enquiring about the why of civilisational collapse, with the top-notch ‘climate scientists’ today marvelling about the how…].

Together with colleagues, he is trying to develop models that can explain complex and large-scale interrelationships in our society [oh, goody, more ‘models’ to curtail human freedoms; remember the ‘models’ of Professor Neil Ferguson of Imperial College that underwrote the Covid lockdowns]. ‘Fridays for Future has influenced politics and consumer behaviour has an impact on the climate. We try to depict such correlations in a serious way’, explains Heitzig. The aim is to understand interactions, not to make predictions [here’s a suggestion, you geniuses: try studying the impact of the Covid lockdowns on CO2 emissions and let me know what you find, will you?]

[Oh, wait, we can see ‘the effect’—a blip in the CO2 emissions, which is a clue—but did that (first) lockdown actually change the CO2 emissions trend? Well, here’s the answer, as certifiable as possible, via the Mauna Loa Observatory (my edits)]

[I would ‘suspect’ that we do have an answer: the most expensive and virtually global experiment in ‘locking down’ to ‘save the climate’ resulted in…no changes in either trends nor CO2 variation in general—no wonder these nutjobs wish to abandon Science for good and rely on ‘intuition’ instead…]

Indications of a Collapse?

Inevitably, the question of a possible collapse comes up. ‘In the current civilisation, we see that there is a very, very high degree of international dependency in the economic system’, Heitzig says. Such dependencies make societies less resilient. ‘There could be domino effects that are comparable to multi-organ failure in humans.’

However, Heitzig is not as pessimistic as the ‘collapsologists’:

I would agree that there are some indications that civilisation could collapse, for example, as a result of a globally escalating violent conflict or a severe global economic crisis.

Both could be exacerbated by the consequences of climate change. ‘But there is no clear evidence that this will actually happen or how likely it is.’ [oh, look, Dr. Heitzig said that; orig. ‘es gibt eben keine klaren Hinweise darauf, dass das wirklich passieren wird oder wie wahrscheinlich es ist’].

From a scientific point of view, it is also impossible to make a serious assessment in terms of time: ‘If you’re driving towards a cliff in the fog and don't know how far away it is, the sensible advice would be: “Put on the brakes”’, says the researcher [another stupid comparison; even in fog, most people would drive on roads, and even if there’s a log of fog, people intuitively drive ‘on sight’, eh?].’"After all, we can fight climate change and we can make our society and our economic system more resilient.’ [this may or may not be true, but the problem is: it’s a nonsequitur in terms of an argument…]

Hope versus Alarmism

The ‘collapsologists’ believe it is too late for that. The collapse may start in a few years or may already be underway without anyone noticing. The participants say they are ‘hope-free’ [orig. hoffnungsfrei; this is pathological—remember the ancient myth of Pandora’s Box? After all the bad things emerged, Hope came out dead-last—but for a reason]. They would rather prepare themselves emotionally for the worst. Prinz is even annoyed by interviews in which climate scientists are asked whether there is still hope.

For psychoanalyst Delaram Habibi-Kohlen, founder of the Climate Working Group in the German Society for Psychotherapy (DGPT), the question of hope is only human. She has been working on the psychological aspect of the climate crisis since 2010 and is also an active member of ‘Psychologists 4 Future’ [if you’re asking yourself, ‘WTF?’; also, go ahead, click on that link (and thank me later)]. ‘We can’t live without hope’, she says. The question is what people can hope for. ‘It is illusory that we can continue to live as before.’ On the other hand, being able to lead a life worth living with many adjustments and sacrifices is not unrealistic [I’ll address this in the bottom lines].

It is important to emphasise the danger posed by ecological crises and at the same time to continue thinking about what we want to do, says Habibi-Kohlen. She warns against too much alarmism: ‘It opens up so little room for people’s imagination. Then everyone says: “Yes, what am I supposed to do?”’ [when did it become a good idea to tell psychologically/mentally unstable people that they should continue to ponder their doom? Sounds like shitty advice, as well as malpractice, to me]

Activism Despite Hopelessness

However, there is no sign of resignation in the ‘Climate Collapse Café’, claims founder Prinz. There is no fatalism in the group, knowing that there is nothing left to save. ‘Especially when nothing more can be achieved, it is necessary to fight for everything again’, says the 45-year-old [whatever the f*** that may or may not mean].

Most of the group’s participants come from climate activism, and some have been involved in the Last Generation. Prinz says that all of the participants are still active in one way or another.

Intermission

Rarely does one find that much BS in a single news item, but then again, here we are. What I find most striking is the obvious denial of scientific facts and the pathological determination to drag along everyone who doesn’t feel that way.

We note, in passing, that the intellectual spiritual founder of ‘collapsology’, Pablo Servigny, according to his French Wikipedia entry, holds the following core belief:

After compiling an impressive number of meta-analyses on the worsening of global warming and the depletion of energy, food, forestry, fishing and metal resources, their thesis is clear: ecosystems are collapsing, and the catastrophe for humanity has begun. And it will accelerate. ‘Collapsology’ is the new interdisciplinary science that brings together the studies, facts, data, forecasts and scenarios that demonstrate this.

Honestly, to me, Dr. Servigny comes across as a latter-day doom cultist, and if it wouldn’t be for the above ntv piece showing people who take themselves (?) seriously, it’s hilariously stupid that Servigny claims to have invented a New Science (sorry, Francis Bacon) that his adherents do not follow because they wish to rely on their ‘intuition’. You literally cannot make up that kind of BS.

On Dr. Servigny’s German Wikipedia profile, though, we find out ‘more directly’ about the key drivers of his nightmares:

His interests include ecological transition, agroecology, collapsology, and collective resilience…

Collapsology…emphasises less individual and more collective action.

And thus are revealed the true motives of Dr. Servigny’s activism: totalitarian collectivism, in all likelihood in what (hilariously ‘even’) Karl Marx fashioned ‘Oriental Despotism’, because ‘the people’ must not be permitted to think and act for themselves lest their technocratic betters approve of this.

You literally cannot make this shit up.

Let’s briefly check in with ‘real’ scientists, such as Ulf Büntgen, Professor of Environmental Systems Analysis at the U of Cambridge (faculty profile), and figure out what ‘they’ think about this notion, shall we? (References omitted, emphases as indicated.)

The importance of distinguishing climate science from climate activism

By Ulf Büntgen, npj Climate Action vol 3, Article number: 36 (2024).

I am concerned by climate scientists becoming climate activists, because scholars should not have a priori interests in the outcome of their studies. Likewise, I am worried about activists who pretend to be scientists, as this can be a misleading form of instrumentalization. [emphases in the original]

Background and motivation

It comes as no surprise that the slow production of scientific knowledge by an ever-growing international and interdisciplinary community of climate change researchers is not feasible to track the accelerating pace of cultural, political and economic perceptions of, and actions to the many threats anthropogenic global warming is likely to pose on natural and societal systems at different spatiotemporal scales. Recognition of a decoupling between “normal” and “post-normal” science is not new, with the latter often being described as a legitimation of the plurality of knowledge in policy debates that became a liberating insight for many. Characteristic for the yet unfolding phenomenon is an intermingling of science and policy, in which political decisions are believed to be without any alternative (because they are scientifically predefined) and large parts of the scientific community accept a subordinate role to society (because there is an apparent moral obligation).

Motivated by the continuous inability of an international agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to tackle global warming, despite an alarming recent rise in surface temperatures and associated hydroclimatic extremes, I argue that quasi-religious belief in, rather than the understanding of the complex causes and consequences of climate and environmental changes undermines academic principles. I recommend that climate science and climate activism should be separated conceptually and practically, and the latter should not be confused with science communication and public engagement.

Climate science and climate activism

While this Comment is not a critique of climate activism per se, I am foremost concerned by an increasing number of climate scientists becoming climate activists, because scholars should not have a priori interests in the outcome of their studies [hear, hear; as an aside, this is the same epistemological problem in historical scholarship on virtually everything from WW1 onwards]. Like in any academic case, the quest for objectivity must also account for all aspects of global climate change research. While I have no problem with scholars taking public positions on climate issues, I see potential conflicts when scholars use information selectively or over-attribute problems to anthropogenic warming, and thus politicise climate and environmental change. Without self-critique and a diversity of viewpoints, scientists will ultimately harm the credibility of their research and possibly cause a wider public, political and economic backlash.

Likewise, I am worried about activists who pretend to be scientists, as this can be a misleading form of instrumentalization. In fact, there is just a thin line between the use and misuse of scientific certainty and uncertainty, and there is evidence for strategic and selective communication of scientific information for climate action. (Non-)specialist activists often adopt scientific arguments as a source of moral legitimation for their movements, which can be radical and destructive rather than rational and constructive. Unrestricted faith in scientific knowledge is, however, problematic because science is neither entitled to absolute truth nor ethical authority [remember Tony Fauci’s ‘trust me, I am the Science™’ quip]. The notion of science to be explanatory rather than exploratory is a naïve overestimation that can fuel the complex field of global climate change to become a dogmatic ersatz religion for the wider public [see above]. It is also utterly irrational if activists ask to ‘follow the science’ if there is no single direction. Again, even a clear-cut case like anthropogenically-induced global climate change [I object to the ‘clear-cut’ nature of this example, for it also contradicts the above-voiced argument] does not justify the deviation from long-lasting scientific standards, which have distinguished the academic world from socio-economic and political spheres.

The role of recent global warming

Moreover, I find it misleading when prominent organisations, such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its latest summary for policymakers, tend to overstate scientific understanding of the rate of recent anthropogenic warming relative to the range of past natural temperature variability over 2000 and even 125,000 years [remember the ‘hottest summer in 125,000 years’ of last year?]. The quality and quantity of available climate proxy records are merely too low to allow for a robust comparison of the observed annual temperature extremes in the 21st century against reconstructed long-term climate means of the Holocene and before [so, how does this statement chime with the ‘clear-cut case cited above?]. Like all science, climate science is tentative and fallible. This universal caveat emphasises the need for more research [read: grift] to reliably contextualise anthropogenic warming [because, apparently, we cannot do that as of today…] and better understand the sensitivity of the Earth’s climate system at different spatiotemporal scales. Along these lines, I agree that the IPCC would benefit from a stronger involvement in economic research, and that its neutral reports should inform but not prescribe climate policy [oh my, this is bonkers—why let a politicised institutions, such as the IPCC, get into ‘economic research’? Moreover, it’s again the same paragraph that starts with the notion that the IPCC ‘tend to overstate’ something vs. calling its reports ‘neutral’ at the end of it].

Furthermore, I cannot exclude that the ongoing pseudo-scientific chase for record-breaking heatwaves and associated hydroclimatic extremes distracts from scientifically guided international achievements of important long-term goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate global warming. It is therefore only a bitter irony that the partial failure of COP28 coincided with the warmest year on record. The temporal overshoot of 2023 now challenges the Paris Agreement to keep global warming well below 2 °C. The IPCC’s special report on exactly this scientifically questionable climate target can be understood as a useful example of science communication that fostered a wide range of climate action. The unprecedented recent temperature rise that follows increasing greenhouse gas concentrations [how does that chime with Büntgen’s critique of a priori conclusions?] and has been amplified by an ongoing El Niño event is likely to continue in 2024. This unparallel warming, however, has the unpleasant potential to trigger a dangerous zeitgeist of resignation and disregard—If it happened once, why shouldn’t it happen twice?

A way forward

In essence, I suggest that an ever-growing commingling of climate science, climate activism, climate communication and climate policy, whereby scientific insights are adopted to promote pre-determined positions, not only creates confusion among politicians, stakeholders and the wider public, but also diminishes academic credibility. Blurring boundaries between science and activism has the potential to harm movements of environmentalism and climate protection, as well as the much-needed international consent for sustainable growth and a global energy transition. If unbound climate activism results in widespread panic or indifference, people may think that it is either too late for action or that action does not matter. This argument is not in disagreement with the idea that mass mobilisation as an effective social response to climate change is only possible if society is experiencing sustained levels of risk [again, certainty about such risks is not forthcoming]. Nevertheless, I would argue that motivations are more helpful than restrictions, at least in the long run. My criticism of an uncontrolled amalgamation of climate scientists and climate activists should not be understood as a general critique of climate activism, for which there are many constructive ways, especially when accepting that climate mitigation and adaptation are both desirable options, and that non-action can be an important part of activism.

In conclusion, and as a way forward, I recommend that a neutral science should remain unbiased and avoid any form of selection, over-attribution and reductionism that would reflect a type of activism [too late]. Policymakers should continue seeking and considering nuanced information from an increasingly complex media landscape of overlapping academic, economic and public interests. Advice from a diversity of researchers and institutions beyond the IPCC and other large-scale organisations that assess the state of knowledge in specific scientific fields should include critical investigations of clear-cut cases, such as anthropogenic climate change. A successful, international climate agenda, including both climate mitigation and adaptation, requires reliable reporting of detailed and trustworthy certainties and uncertainties, whereas any form of scientism and exaggeration will be counterproductive.

Bottom Lines

All in all a mixed bag of things. The ‘collapsology’ nutjobs are quite amusing, and the ‘Psychoanalysts 4 Future’ website is a hilarious piece of…well, what exactly?

The same applies to Professor Büntgen’s comment, which, while decrying the ‘blurring’ of climate science and activism, does exactly that.

In both cases, however, we do see pieces of truth, as far as we can determine it, in both cited articles:

In the news media piece about the ‘collapsology café’, we can clearly see the totalitarian collectivist ‘future’ envisioned by those activists who envision a post-collapse human society, although the ntv piece cites a mathematician (Dr. Jobst Heitzig) who clearly states that ‘there is no clear evidence that [collapse] will actually happen or how likely it is’.

In Professor Büntgen’s comment in Nature, we see the contradictions between what he favours vs. what the data shows; moreover, climate adaptation and/or mitigation, described as ‘desirable’ outcomes, have largely vanished from public discourse.

These seemingly exclusionary positions in both cited instances may seem absurd and utterly odd. Yet, if we apply the (pseudo-scientific) ‘model’ underwriting both—what Kant and Hegel infamously called ‘the Dialectic’, which Marx re-imagined—what goes on becomes obvious:

A thesis (the world as it is) is proposed: an impending ‘climate catastrophe’ is proclaimed, based on ‘the Science™’ (for which, let’s remember, Prof. Büntgen admits there exists a certain—in my opinion too big—uncertainty).

The corresponding antithesis (the utopian—collectivist-totalitarian—aim) is the notion that, to avoid the ‘collapse’ of human civilisation, we must, of course, change everything.

The desired synthetic outcome, of course, is found in a more ‘resilient’ future, whatever that means. In other words: ‘climate change’ may be addressed by embarking on a societal transformation into a techno-collectivist utopia that’s waiting for us if we only continue marching ‘forwards’ following the totalitarian indications of our betters. This time, we’ll certain find the proverbial pot of gold at the end of the collectivist rainbow.

This is all, of course, bonkers.

Legacy media and academia are mostly gone, which is the main take-away of these pieces. Whatever future shape human society will eventually take, one thing appears quite certain: new institutions will (continue to) emerge, and eventually they will supersede the current ones.

The next few decades will become increasingly weird on many levels: the UN/WEF ‘Agenda 2030’, the ‘Gender™’ confusion, and, of course, ‘Climate Change™’.

I suspect that things will begin to turn around visibly before too long, if only because of the impending shift from less leftish-fetish believes (mainly because these people have fewer children than ‘conservatives’), and this will quite likely drag along most of the rest of society.

Buckle up.

What do your academic colleagues think of your extremely based and redpilled articles?

To answer the question of why a panic in Europe?

24/7/365 propaganda for decades.

In the 1970s and 1980s, it was tangible and demonstarbly dangerous emissions from capitalist corporations that was the focus of any environmentalist movement.

Then, as the Wall came down, Green parties started to take place in parliaments. Soon, they became the pests we now them as today, lavishing punitive taxes and fees on the common people while not saying word one about ftalates, PFAS, glyfosat, bromides in electrnics, vaccines, hormonal waste in water, windmills massacring birds, and so on. Not a peep.

Call me Mr Suspiscious but it sure does seem they were captured one and all by global capitalism in the mid-to-late 1990s.