'Children experience strokes differently'

Apparently, this is part and parcel of the New Normal, as per the Austrian Science Foundation's research weblog

Something I found on the internet. Weird shit, but, hey, the Science™.

Emphases and [snark] mine.

“Children experience strokes differently”

The international “Build Care” project explores how built environments affect the everyday lives of children after a stroke. Architects, health economists and neuroscientists used a multidisciplinary approach to develop design recommendations shared with experts and affected individuals on an online platform. The objective is to improve the lives of such children and their families.

By Sophia Hanak, Scilog / FWF.ac.at, 20 Oct. 2025 [source; archived]

Strokes in children are rare and often detected late [when did ‘strokes in children’ become ‘normal’?]. Those affected and their families have to live with the consequences for the rest of their lives. A research team led by Maja Kevdžija from TU Wien (Vienna University of Technology) is investigating what role informal (home, neighborhood, school) and formal (hospital, rehabilitation clinic, outpatient clinic) care environments play in the everyday lives of children and families affected by childhood stroke.

Co-funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), the project focuses on child stroke patients between the ages of six and fourteen and explores how these families experience everyday life in different environments: “We look at everyday environments, from home to school to hospital and rehabilitation centers,” notes architect Maja Kevdžija. In collaboration with partner institutions, including TU Dresden, KU Leuven, the Medical University of Vienna, and the Research Unit for Public Finance and Infrastructure Policy at the Department of Spatial Planning at TU Wien, Kevdžija addresses this issue, about which there is scant research to date [do you see the normalisation now?]

In order to find out how the environment can support the recovery of these children, the researchers visited affected families at home, mapped the rooms there and conducted interviews. “A total of 30 families were directly involved in the project: 11 in Austria, 15 in Germany, and 4 in Belgium. Over 150 additional families from the three countries took part in the socioeconomic survey,” explains Kevdžija. Birgit Moser, a doctoral student of architecture at TU Wien, even developed a game called “Space Agents” that made it easier to talk to the children about their everyday lives.

In ethical terms, the project is a challenge. While cooperation with the families went well for the most part in Austria and Germany, the ethical requirements were particularly challenging in Belgium, as Kevdžija reports. In order to overcome these problems, the team worked with existing material such as autobiographies and videos. By now, the researchers have produced a publication that reflects on the use of data from experience reports and findings in connection with ethical aspects [that study is a gem—wanna ‘guess’ when these people began their enquiries? Why, 2021, of course…].

Therapies in the classroom and at home

For adults, the post-stroke agenda is usually clearly structured, from diagnosis to hospital to rehabilitation and the return home. For children, the path is completely open in most cases: “There is no clear process for a child stroke patient,” says Kevdžija. Every child has their own path, because there is a wide range of impairments and great differences in care and environment.

“Hence, the goals of rehabilitation and recovery in children are very different,” says Kevdžija, who currently occupies a research niche with her focus on design requirements in the healthcare system. While the goal for adults is often to regain independence, it is much more than that for children: long-term development, academic performance, social integration and future career opportunities are at stake. This makes the role of the environment all the more essential.

A core finding shows that schools are much more important for affected children than previously thought. “We learned that they are not only places of education, but also of therapy,” explains Kevdžija [now we’re venturing into therapy for everyone, because no-one is safe unless everyone’s safe, right?]. Many children attend regular schools, others attend specialized institutions, and some children receive their therapy directly at school. At the same time, they develop individual ways of dealing with difficult situations there: “School is a very important place for affected children, and they have various strategies for regulating their emotions, for example by retreating to a special place,” says Kevdžija.

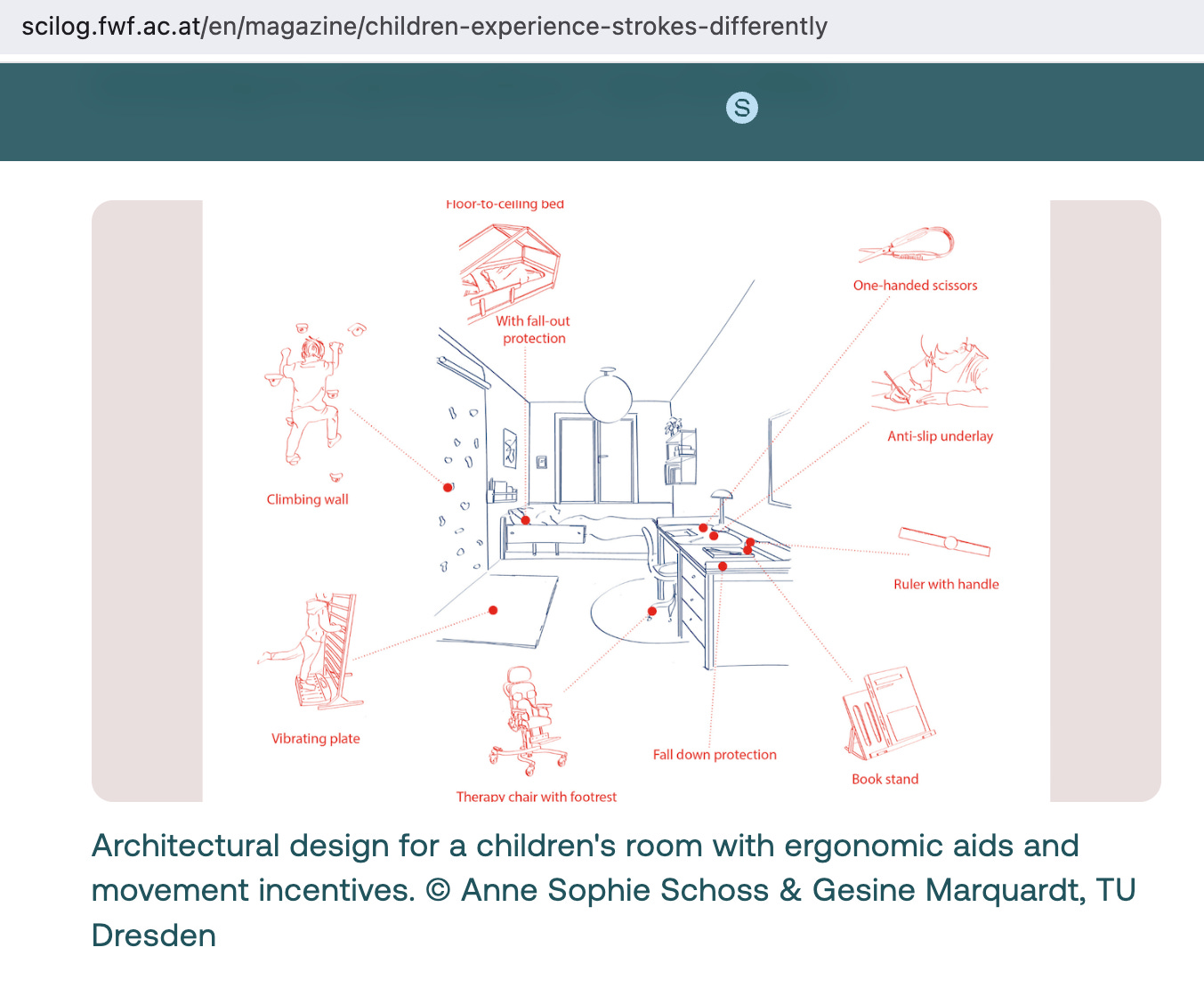

Socioeconomic barriers to structural adaptations

The everyday lives of these children are fraught with many challenges, such as getting dressed, leaving the house, or doing homework. But it has become clear that the built environment can be helpful. “Parents do things such as integrating climbing walls into their homes, or encouraging their children to climb the stairs on their own. In this way, they make the environment part of the therapy.” A telling point in this context is the fact that the socioeconomic status of the parents has an impact on the cognitive recovery of the children [some would say that’s true across the board in a general way, but hey, doing so would be class-ist, isn’t it?].

This is a finding from studies conducted by the partner group under the lead of neurolinguist Lisa Bartha-Doering at the Medical University of Vienna. “How well a child recovers also depends on the parents’ level of education and financial resources,” [no-one knew, I’m glad the Science™ could help us out on this one *sarcasm*] emphasizes Kevdžija. Those who have more resources at their disposal find it easier to access and pay for therapies and home redesigns. Initial analyses of the socioeconomic survey of 155 families in all three countries were conducted by the researchers in the Public Finance and Infrastructure Policy Unit at the Spatial Planning Department. They reveal that many families do make structural changes. More often than not, such changes were made to the bathroom. Some families would like to make (further) adjustments to their homes, but identified financial or time constraints as the main reasons why they have not done so yet [but it’s important to adjust school for everyone rather than, say, targeted, needs-based help for individual families: One Health requires a Common Core].

Design tips for families, designers, and therapists

The team now wants to use the results of the research project to develop recommendations for families as well as for architects and medical professionals. “We developed a persona-set that can be used by both designers and families,” says Kevdžija. The results will be made publicly available on an online platform at the end of the project late 2025. “I hope that our project will raise awareness of how much the built environment can support or obstruct,” says Kevdžija. “And I hope that the strategies we offer will help families create supportive spaces for their children.”

When children suffer a stroke, it affects their entire living environment. The project impressively demonstrates how important it is to provide these children with holistic support, to design spaces that make their everyday lives easier but also offer them a challenge to work out and practice skills when necessary, while providing support to their families.

In addition, the project is already inspiring new collaborative efforts: The Medical University of Vienna is now working with the architecture partners on a proposal for a Horizon project in which the findings will be further developed. Both TU Wien and MedUni Wien are expected to be partners in this endeavour. BUILD CARE thus forms the basis for future research and the networking of different disciplines and demonstrates how interdisciplinary collaboration provides tangible input for science and real-life application.

BUILD CARE project

Set to run until the end of November 2025, the international research project “Building support for children and families affected by stroke” (BUILD CARE) has been awarded EUR 238,000 in funding by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF). The research on BUILD CARE is complemented by a further FWF project. At the Medical University of Vienna, a working group led by neurolinguist Lisa Bartha-Doering is investigating visual impairments in children and adolescents after a stroke. Visual impairments such as object recognition, spatial orientation, or visual memory can add hurdles to the children’s everyday life, mobility, and independence.

Bottom Lines

Mind-numbingly, I read every single reference cited in the above-linked paper (‘The space between procedural and situated ethics: Reflecting on the use of existing materials in design research on children affected by stroke’).

There is, unsurprisingly, not a single reference that refers to the terms ‘childhood stroke’.

The National Library of Medicine contains 3,436 references to this term (1953-2025), 1159 of which relate to the period since 1. Jan. 2021. That’s a third of these entries.

Isn’t this amazing? I mean, the entire project talks about ‘childhood strokes’ and there’s not a single reference to specialist literature.

My verdict is—yes, these aren’t medical specialists, but this is yet more grift-in-the-making.

Having a sick or otherwise impaired child is horrible; but I’m more enraged about these grifters than anything else.

O tempora, o mores.

I think they copied how you build enclosures for zoo- and lab-animals.

And not a single mention of reasons for strokes in children.

I did a quick search for "stroke barn" in Swedish and found an organisation for stroke victims, that listed heart diseases, coagulant-imparing/affecting diseases, systemic illness whatever that means, traumas and infections, and mumps.

Immediate thought: there's a clear overlap between known mRNA-shot side effects and this.

the following paragraph to me proves that it's a grift (in my language we call it 'fried air'), because right in the first sentence one can take out the words 'a stroke', in the following sentence the word 'these' and the rest still remains the same blah-di-blah blatter: "...When children suffer //a stroke//, it affects their entire living environment. The project impressively demonstrates how important it is to provide //these// children with holistic support, to design spaces that make their everyday lives easier but also offer them a challenge to work out and practice skills when necessary, while providing support to their families....".

nice find, thanks for posting.