Woke Feminist Journo 'Tries' to Join the Army

Ability to Express Opinions and Social Compatibility Aren't Good Enough, Because the Army Also Requires Adequate Cognitive and Physical Skills

Today, I’ve had a good laugh while sipping my morning coffee: a female (?) journalist working for the woke-fied Austrian legacy media outlet Der Standard wrote a piece about her ‘lived experience’ while (pretending) to pass the recruitment test for the Austrian Army (Bundesheer).

Why, one might ask? Well, according to the piece in Der Standard, it’s been a quarter-century since the third wave of feminism managed to corral the Army into accepting women into their ranks (for the US version, do see ‘GI Jane’ [/sarcasm]).

So, without much further ado, I’ll let Sandra Schieder to the womansplaining of her ‘lived experience’. Here’s the link to the original article, which appeared on 21 May 2023. As always, translation, emphases, [brief comments in squared parentheses], and bottom lines are mine. Note that the pictures are from Ms. Schieder’s original piece; I’m reproducing them as they appear in the original piece for illustrative purposes while all copyrights remain with the original creator and/or Der Standard.

How I Failed the Entrance Exam to Become a Female Soldier

Almost half of all women who want to become soldiers fail the entry-level test. ‘It can't be that difficult’, our journalist thought—and was proven wrong during a self-experiment.

It’s three o'clock in the morning, I’ve been awake for 22 hours, and I’m sitting in a empty training room in the Hessen barracks in Wels. In front of me is a small, white, round box containing 50 screws, nuts, and washers of different sizes and shapes. The task is to find the right nut and washer for each screw, screw them together, and place them on a board in front of me. Then the screws have to be unscrewed again and all the individual parts placed in another box. The need for sleep persists for hours, my eyes keep falling shut. ‘What the hell am I doing here anyway?’, I ask myself, and I have to remind myself that I am here voluntarily.

‘All these exercises are done to make you exhausted for what is yet to come’, says Vice Lieutenant [highest non-commissioned officer rank in Germany and Austria; it’s US equivalent is Master Sergeant] Michael Aichinger. ‘For what is yet to come?’, I think and I am quickly pulled out of my thoughts when I hear that it is now time to go into the bunker. It is pitch dark as I, together with twelve others, walk a few minutes across the barracks grounds before a staircase leads us into a 40-square-metre basement room. The bunker, where each of us is allocated a seat, is half that size. Before the room is filled with disco smoke and loud music, we are given a clipboard with several pieces of paper and a pen. Now we have to solve tasks under time pressure, such as search for rows of numbers and letters, find differences in faces. The fog clouds the view, not to mention the disturbing music. I want to go to bed.

What brought me here had begun completely innocently—with an anniversary. For a quarter of a century now, the doors of the armed forces have been open to women. The first women enlisted on 1 April 1998. As of April 2023, there were 640 female soldiers, making up 4.3% of the total [yes, you read that correctly: there are approx. 15,000 professional soldiers in the Austrian armed forces]. Female soldiers are still a rare species, even though their share is increasing. Almost half of the women who want to become soldiers fail the necessary aptitude test.

Reporting for Training Service

‘It can’t be that difficult’, I thought to myself and decided to go through the entrance procedure that has to be passed in order to take up a career as a female soldier myself. Anyone who wants to join the army must first sign a voluntary declaration for training service in accordance with section 37ff of the 2001 Military Service Act—including me. With my signature, I confirm at the army’s [recruitment offices named] ‘Checkpoint Mahü’ on Vienna’s Mariahilfer Straße that I am voluntarily reporting for service for a period of twelve months. Beforehand, my military service advisor, Captain René Smode, explained to me that I can withdraw my voluntary registration at any time and without giving reasons [talk about absurdity in terms of business economics: why potentially invest serious money into volunteers who could, technically, resign at any time and then, for instance, sell their military skills to private military contractors, such as ‘XE’ (formerly known as ‘Blackwater’) or ‘Wagner PMC’, to say nothing about the issue of mal-investment or public accountability]. That’s good to know, after all, I don’t really intend to quit my job at Der Standard and instead defend the fatherland with my weapon in an emergency [anyone else up for wasting taxpayer money?] A few days later I receive a letter from the Army Personnel Office and am summoned to Wels for the entry-level test.

At the end of April, I finally stand somewhat lost on the huge grounds of the Hessen barracks and, after ‘checking in’, move into a room with six bunk beds with two other women [talk about sex-based discrimination: I remember that, 25 years ago, no bunk bed was left unoccupied, even though I would have very much appreciated a bit more of privacy during military service]. Since I am not on an undercover mission, I ‘out’ myself to them as a journalist. Before going to bed at 10 p.m., Verena Riedmüller and Kathrin Strobl tell me that they want to pursue a military career, i.e., a career as a non-commissioned officer or officer. Until a few weeks ago, this was the only option for women; since 1 April, they also have the option of ‘voluntary basic military service’. For both women, the next day is about a lot—their professional future.

‘We want you, Ms. Schieder’

Anyone who wants to become a soldier must first meet the physical requirements. The first hurdle of the three-day aptitude test is therefore the medical examination. Shortly after six o’clock in the morning, everyone takes the bus to the recruitment premises in Linz. There we are moved through many tests: height, weight, blood pressure, and heart rate are measured. In addition to a vision and hearing test, a lung function test is also carried out. Blood is also drawn and a urine sample has to be given.

On this day, the first athletic hurdle awaits me: ten minutes of pedalling on the ergometer, at an increasing load. If you don’t pass the cardio test, you are disqualified from all subsequent physical tests. I grind my teeth, pedal—and pass.

In order to enter a military career, the result of the medical examination must be ranked between scores 5 to 9. Before heading back to Wels in the late afternoon, Vice-Lieutenant Aichinger reads out the rating numbers. ‘Who is the healthiest of them all?’ he asks the group. He immediately gives the answer himself: ‘The journalist. We want you, Ms. Schieder!’ My test result for this part is an 8.

For 20% of the women, the entry-level test ends on the first day. So it did for Kathrin Strobl. ‘The reason for this is that I was diagnosed with Long Covid a year ago and my lung function is not yet sufficiently intact again’, she explains to Der Standard. In six months, the 19-year-old from Salzburg, who graduated from the sports high school in Salzburg, wants to try again.

The hardest day of the aptitude test is day two: language, physical, social, and cognitive skills are tested—for 24 hours without sleep.

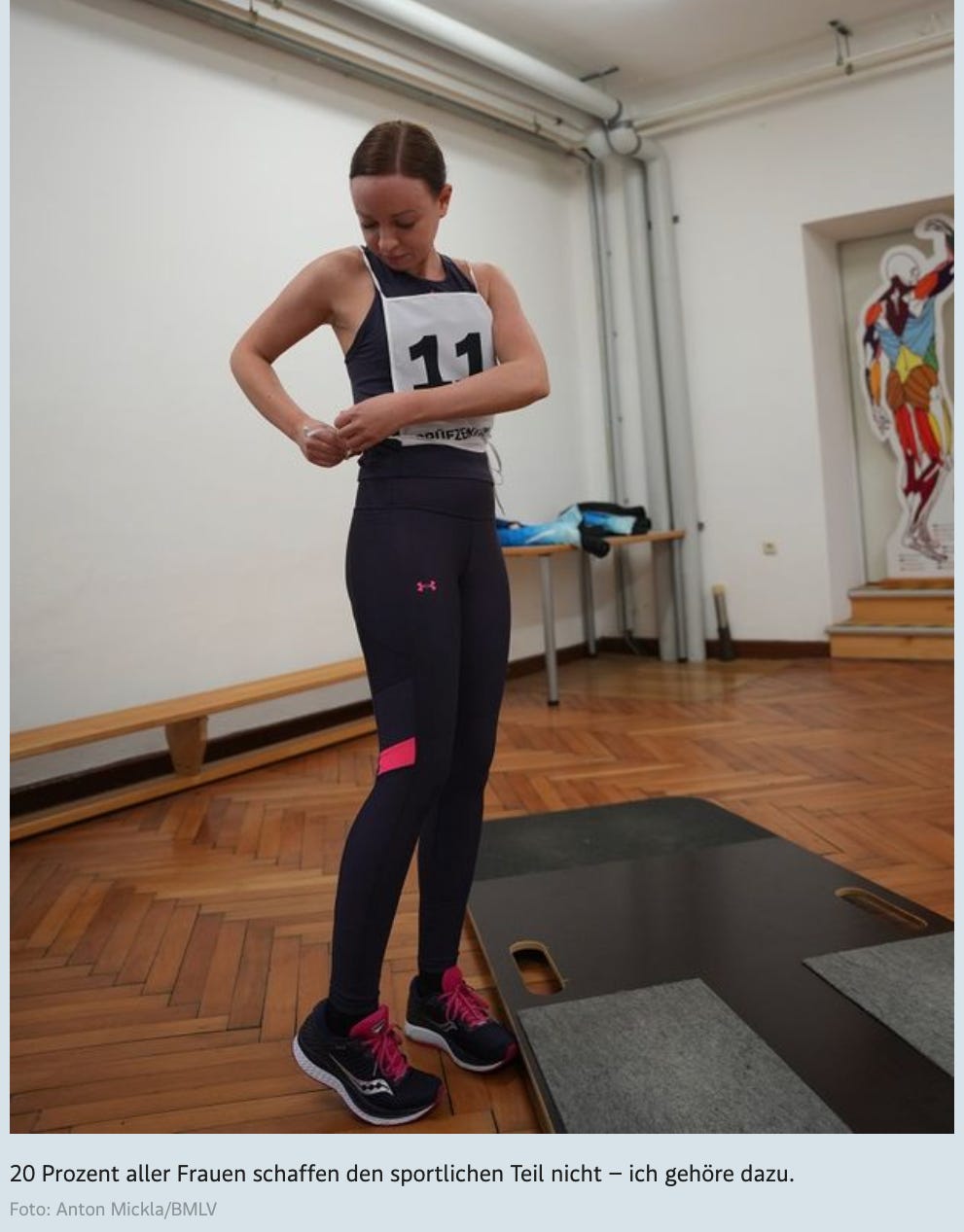

It starts early in the morning with a German test, which turns out to be child’s play for me. Having an opinion on a given topic and putting it down on paper is no problem, even when I’m half asleep. The physical part proves to be a much bigger challenge. One has to prove oneself across five disciplines. Different performance limits apply to women and men [remember: 20% of all female applicants don’t make it to day two, even though sex-based differentials—as reasonable and justified as they are due to biological differences—continue to apply]. ‘Physical fitness is the foundation of every soldier. No matter how much of a highbrow you are, you can’t do it without sport’, Colonel Christof Fehrer will later say. 20% of all women do not pass the physical bar [the piece is unclear if that’s another 20% who fail on day two or if this share applies across the three-day test].

The Tip of the Nose Must Touch the Floor

Here we go with my athletic nemesis, push-ups. I do several [how many? We’re not told]. The photographer is satisfied, the drill master is not. Several times I am asked by him to go further down. I don’t manage a single one in the fashion required by the army—move the body parallel to the ground and then so far down that the tip of the nose almost touches it. In the end, none of my push-ups count.

The 2400-metre run shows that my endurance is better than my strength. I completed it without much effort in 11 minutes and 52 seconds [i.e., approx. 4:45 per km, i.e., not much faster than jogging]. I also pass the swimming test in the evening without any problems. Half an hour after midnight I have to perform jumping as high as I can and pull-ups on an incline. I did well on the first, and was just as brilliant on the pull-ups as I was on the push-ups.

During lunch break—a military principle is ‘no fighting without eating’—I get to talk to Verena Riedmüller. The 32-year-old has prepared well for the admission procedure, ‘both for the physical and the theoretical part’. The Lower Austrian would like to be part of the armoured infantry or work for the military police. The fact that the army is male-dominated does not bother her: ‘I do think that women have to assert themselves more in male domains like the army, but I think I can do that too.’ She thinks it’s good that women have to do the same as men, ‘anything else would be unfair’. [but women don’t have to perform at the same level as men, as the article mentioned before; talk about a contradiction in terms…]

Socially Competent, Cognitively Inadequate

I am having a few jitters before the psychological examination on the third day. On the previous [second] day, social skills were tested in individual and group exercises, i.e., my self-confidence, motivation, rhetoric, stamina, ability to work in a team, critical faculties, leadership qualities, and so on. My behaviour was observed and evaluated by people trained for this. I also learn now [on day three] how I did in the cognitive tests, which were mostly done on the computer. Abstract thinking and solving tricky tasks have never been among my strengths.

The day before [i.e., day two], several questionnaires had to be filled out for the psychological examination. If you want to join the army, you have to reveal much more about yourself than your CV says. Compared to other questions, those about parents and siblings seem harmless. Other questions are aimed at dealing with alcohol and drugs, psychological problems, financial situation, involvement in legal disputes, problems with law enforcement, and other private difficulties. It is better not to have anything to hide here. [wow, much like teaching at schools, right?] At one of the questions I think about telling a lie, but then I don’t dare to, after all I confirm with my signature that I have answered the questions truthfully.

Finally, I learn from military psychologist Susanna Schweiger that I scored 100 out of 100 in the assessment of my social skills, but that the results of the cognitive tests are not sufficient for a professional military career. At least my test result in German certifies eligibility, anything else would have been a disgrace. [but in general, Ms. Schieder isn’t fit for service, which is kinda omitted here] My overall result: temporarily not suitable, eligible for another attempt within twelve months. ‘Our task is to make a prognosis of how much time it will take to develop those skills that don’t fit the requirement profile at the moment’, explains military psychologist Barbara Pawlowski. In my case, they decided on the ‘shortest possible development period’. You are called up for re-enlistment either in twelve, 24 or 36 months. The Army doesn’t want to talk about a ‘insufficiencies’ until then, the wording used is ‘development period’. [i.e., try to ‘learn’ to make it through the computerised IQ test]

Verena Riedmüller is eligible for service. ‘I am really very relieved and pleased’, she tells Der Standard. The aptitude test had already been exhausting, but it had also been fun. Her military service training starts at the beginning of September in Amstetten. I, on the other hand, am offered tips to compensate for my cognitive deficits and a training plan for push-ups and pull-ups.

No thanks, it was a one-time affair for me.

Bottom Lines

This is what passes for ‘journalism’ these days.

Mind you, I’m not gloating about this (even though the revelatory stupidity made me cringe—and, then, laugh), but if there’d be any more ‘proof’ required about sex differences and the continuation of sex-based discrimination at the hand of the state via different standards for male and female recruits, well, what else would be there?

It’d be almost absurd to invoke Jordan Peterson stating the same in as many words: do we really mean what we say when we’re invoking 50:50 equality between the sexes? Good luck doing this with the military or law enforcement (where, truth be told, many male applicants fail due to limited cognitive capabilities right after high school, to say nothing about physical differences…).

Still, Ms. Schieder’s piece is instructive for the following three main reasons:

She’s been a staff writer for Austria’s chief woke-fied news outlet, Der Standard, which was among the most hawkish Branch Covidians (just check out almost any piece I’ve written on Covidistan), yet she admits to jitteriness when lying because she’d have to sign an affidavit. No such statements—or criminal penalties—are due after publishing nonsense in legacy media.

There’s also the notion of Ms. Schieder’s lack of cognitive abilities, which certainly disqualified her from military service but that’s no obstacle for a ‘career’ in legacy journalism (and don’t get me started on the editorial board that elected to publish this stream of conscisousness-esque parody of a ‘what I did last summer’ essay in junior high). Pathetic and embarrassing are the two least-inflammatory words that spring to my mind.

Finally, this is as comically absurd an example of a member of the chattering, white collar-wearing, and laptop-wielding classes literally claiming ‘it can’t be that difficult’—and subsequently learning that, yes, it actually is a wee bit more tricky than it looked at the outset. Here, I’d argue, Schadenfreude is very well in order, in particular since Ms. Schieder and her ilk over at Der Standard had no problem passing (moral) judgement on their non-conformist fellow-citizens because ‘The Science™’.

So, as cringe-worthy and patently stupid as it is, Ms. Schieder at least tried to reconcile her ‘this doesn’t look that difficult from the comfort of my office chair’ attitudes with first-hand experience.

True, she didn’t like it a bit, and, yes, she proudly admitted to her own incompetence.

Still, I’m left wondering: if she contemplated lying under oath and didn’t do it because of legal implications, is this the same journalistic standards practiced by her employer, Der Standard (pun intended) or other legacy media outlets? Whatever your answer, it’s not pretty, eh?

Finally, I’d argue that Ms. Schieder and her ‘colleagues’ over at Der Standard have no shame or sense of proportionality (left) as the above piece is an indictment of both its author and the Standard’s editors.

Sadly, neither will face serious consequences for their failures.

Tests when european nations still had conscription and mass-armies were by necessity much easier than the ones for today's professional soldiery.

So it's no wonder she doesn't qualify, and it's very telling that she is a product of a school-system an society where you pass/fail based on a percentage of the whole.

A military, fire department, other emergency services or police cannot function on a member being 75% competent; when that gets implemented, we might as well go back to mass-conscription anyway.

I don’t believe she would have any difficulty joining the Imperial Military here at the center of Empire. She seems to have all the required qualities. ;-)