The Eclipse of Higher Education

Snippets from the frontlines of socialist perf-prop (for 'performance-propaganda')

Every now and then I revisit themes I once wrote about to see how far my musings were true. Today, we shall do so, and we’ll do so in light of the recent campus upheavals that relate to ‘current events’. Mind you, I’m the messenger, and it’s not up to me if you dislike my conclusions.

We’ll start, briefly, with a link to a long-ish exposé from two years ago:

It would appear that the western love affair with ever more (and ever pricier) education is coming to an end, though. Those who paid attention already saw the cracks in the system, in particular if one was watching esp. US academia with its many travesties, ranging from sky-high tuition fees (that cannot be discharged via individual bankruptcy) to the questionable business plans (ahem) of many private liberal arts colleges to the inexorable rise of adjunct temporary faculty. Note that these problems predate the emergence of ‘wokery’, which in many ways did work like an accelerant anyways.

And then—Sars-Cov-2 and Covid-19 ‘happened’, adding further fuel to the already-burning dumpster fire masquerading as higher education.

In my article, I made two core claims:

Citing ‘the Knowledge Economy™’, gov’t would demand ‘more graduates’, although neither Big Gov’t nor Big Business would do anything to improve working conditions (salaries), implement anything consistently, or follow an overall strategy.

All existing problems (bad student-faculty ratios, higher numbers of drop-outs, downward pressure on wages, grade inflation, less competence, etc.) would be worsening and eventually spill over from one sector—Big Healthcare—to the other (Big Education).

And now, lo and behold, we seem to have reached that point in time, if a few pieces about looming shortages of doctors and nursing staff—and excessive costs for temporary replacements of between US$ 20-30K per week (see, e.g., here or here)—in state media are any guide.

Below, we’ll discuss one of the core problems feeding into these issues, namely academic training, widely held as ‘the’ panacea and sine qua non of ‘the Knowledge Economy™’ of the 21st century.

All translations and emphases are mine, as are the bottom lines.

‘Everyone’ Wants a Master’s Degree

The number of applicants for two-year master’s programmes has almost doubled in ten years. This year, the numbers continue to rise at several universities.

By Linea C. Søgaard, NRK, 2 May 2024 [source]

Alexander Lundgren (27) throws his arms to either side and cheers: ‘This is a great achievement for me, because I've never been good at school’, he says. The 27-year-old has just handed in his bachelor’s thesis. This means that he can now call himself a kindergarten teacher. [you read this correctly: an undergraduate degree at the tender age of 27—to work in kindergarten (!!!)]

Actually, Alexander would really like to get a job now. At the same time, he fears that he will have few job opportunities later on if he doesn’t continue his education. [this is the problem—outdated and patently absurd demands about education now for career advancement 20 years hence, to say nothing about what this does to family planning]

I fear that a bachelor’s degree won’t be enough later on.

The Dilemma

There’s been a lot of back and forth in recent months. On the one hand, it seems great to pack up the textbooks and earn money. On the other hand, a master’s degree will probably provide more career opportunities and better pay.

Alexander takes the last sip of the coffee he needs to wake up. Then he sits down at the university library in Horten, where he has spent a lot of time in recent months. If a master’s degree is required in today’s labour market, it’s something he will consider [mind you, that such a degree will take years to do, and ‘today’s labour market’ will soon be a thing of the past].

I just want to reach the current standard.

Twice as Many Apply for Two-Year Master’s Programmes

In 2013, around 44,000 people applied for a two-year master’s programme. In the ten years since, that number has almost doubled. [you know, there’s only one other thing that grows like that: cancer]

In general, this year’s application figures show a large increase in applicants to universities compared to last year [kinda untrue, as Statistics Norway explains: 2022: 297,775 vs. 2023: 299,062], but this year’s master's applications have not yet been collated or published in one place.

NRK has therefore asked several of the largest universities about their application figures.

The University of South-Eastern Norway, where Alexander is studying, has a record number of applicants for a two-year master’s degree this year and a growth of 70% in five years. [now you see why I brought up the cancer quip]

The Arctic University of Norway, the University of Stavanger, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, and the Norwegian University of Life Sciences have also seen an increase.

NTNU, OsloMet, and Inland University of Applied Sciences have seen a slight decline.

Master’s disease?

The question of whether we have a ‘master’s problem’ in Norway has been debated for several years. After [former higher ed minister] Sandra Borch (Sp) and [former health and human services minister] Ingvild Kjerkol (Ap) had their master’s theses invalidated due to plagiarism, the term has resurfaced.

But in Norway, a smaller proportion of the population has a higher education in the form of a master’s degree or doctorate than in other countries such as Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. [talk about ‘the Nordic model’, eh?]

Nevertheless, Alexander and several other students NRK has been in contact with experience ‘master pressure’.

Investing in a master's degree is a good idea, according to Ingvild Stakkevold Reymert. She is a researcher and head of department at OsloMet Business School. The fact is that people with a master’s degree are sought after by employers. [but she omits what kind of master’s degree is more helpful than others…]

According to NHO [Næringslivets Hovedorganisasjon, or Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise, i.e., something like the business roundtable] Competence Barometer, about half of NHO’s member companies want employees with a master’s degree. In addition, she believes that a master’s degree provides security in a changing labour market.

Recommends Choosing What You Want

Rebekka Borsch is Director of Expertise and Innovation at NHO [what a job title for a lobbyist]. She thinks people should choose what they are most motivated to do and not take a master’s programme because of pressure [talk about bad incentives…].

Because many jobs don’t require a master’s degree, she believes it’s fine to go out into the labour market and study further if you need or want to. However, practical experience is also valued by employers, according to the NHO director:

Young people shouldn’t worry about getting a job. I think we will need everyone we can get a hold of in the future.

Young People Want a Flexible Work Life

Bachelor student Alexander opens his computer. The screen reads ‘Master of Education’ [oh my…]. After his last internship in the spring, Alexander was pretty sure that he didn’t want to work as a kindergarten teacher for the rest of his life, even though he enjoys it:

Having a master’s degree feels like a guarantee of a more varied working life. [somebody should tell him…]

He has therefore made up his mind: he will do a master’s degree in the autumn [2024]. But he also wants to work full time [at least something].

The combination is perhaps the closest he gets to the best of both options. The master’s programme is part-time over four years [he will graduate in June 2028, if he manages to do this according to the plan; many students fail to do so without working—my best guess would be 1-2 years delay, so, just about ‘in time’ for the labour market of the 2030s…].

Alexander packs his bag and leaves the library. Soon he will be taking a real summer holiday from theory-heavy subjects.

In the meantime, he has a couple of job interviews to attend.

If all goes according to plan, he’ll have both diplomas and experience that could come in handy in job interviews in a few years’ time.

Bottom Lines

This won’t end well. As the above-linked piece by Statistics Norway indicates, higher education enrolment has increased massively in the past 25 years:

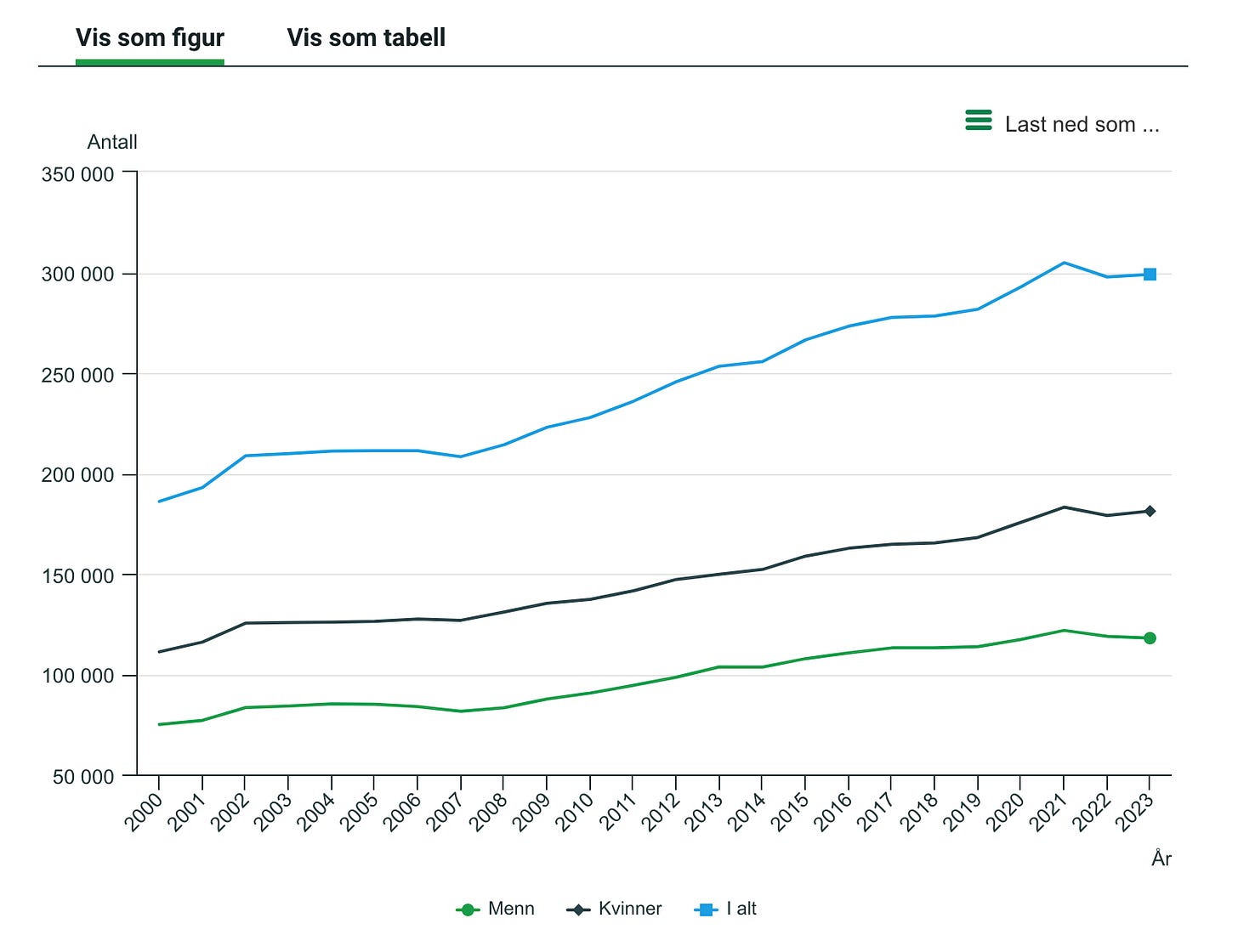

Caption: ‘menn’ = men; ‘kvinner’ = women; ‘i alt’ = combined.

In 2000, the numbers were 74,914 men; 111,088 women; total: 186,002.

By 2023, these rose to 117,897 men (+57%); 181,165 women (+63%); total: 299,062 (+60%). Approx. 60-61% or all students in Norway are women.

Given the tendency of women looking for ‘better’ partners (hypergamy), this trend will massively, I think, compound fertility and birth rate issues in the near term.

At the same time, the gov’t push to increase the share of graduates per generation will, according to time-tested features (‘markets’), decrease the value of each successive diploma. Undergraduate degrees (‘bachelor level’) were introduced approx. 25 years ago, and now ‘even’ 27 year-old graduates, such as Alexander, realise that it is basically worthless. I doubt that his ‘calculation’ (guess/hope) about obtaining a master’s degree—in ‘education’, of all disciplines—will materialise anytime soon. If anything, I think it’s both disingenuous of the powers-that-be to tell the young people to ‘get an education’ before, you know, a job and a few kids, to say nothing about the societal implications.

None of these things are new, by the way, and I shall quote from a treatise by 18th-century enlightened reformer Joseph von Sonnenfels (1732-1817, Wikipedia bio), who, when the Habsburg empress Maria Theresa (r. 1740-80) considered increasing education levels of her subjects to boost their productivity and hence tax payments, wrote the following—scathing and prescient, in my view—words:

Instead of the schools providing the offices with the required number of useful candidates, new magistrates [Ämter] were created to absorb the sheer masses of students and provide them with something…Offices were multiplied to get rid of the impetus of the fathers and their families who treat their official title as necessary accoutrement [Verzierung] without which one may not appear in public. One must to be something, sayeth those who, irrespective of their official title, will never be someone.

These lines were written in 1771 by Sonnenfels in his treatise ‘On the Disadvantages of More Universities’, and I will conclude that they were, by and large, true then—as they are today.

(Lest you ask: I’m currently writing a book about crime, bureaucracy, and punishment in the late 18th century, which also features a chapter about ‘education’…go figure.)

We are apparently going to repeat past mistakes, which will end with comparable results.

Government wants more university-trained citizens presuming that they will be more productive = pay more taxes. Big Gov’t, esp. here in Norway, also sets the prices for labour (via so-called tripartite agreements with Big Labour/Unions and Big Business/Employers).

The additional costs this will impose will be borne by regular people, to say nothing about the absolutely resulting ‘collateral damages’ in terms of extended adolescence, the prioritisation of ‘training’, followed by a ‘career’, over (work) experience and family life.

This won’t end well.

Peter Turchin has mentioned that when elite competition increases and life crappifies for the masses, university enrollment increases. So, this isn't so surprising.

I do wonder how the smaller cohort sizes will play into this, though. We're probably very close to the ceiling of how many people (relative to cohort size) can enroll in university, given the distribution of talents and inclinations. As the number of young people drops, so will the number of students. But as the number of young people drops, you can expect employers to compete more vigorously for the few who are there, resulting in a smaller percentage of a smaller cohort attending university. Probably.

The one thing that bothers me, though, is that human organizations are so bad at contracting in a rational manner. For instance, I read somewhere recently that the number of newly-minted history PhDs (in the United States, I believe) had shrunk by something like 30% compared to about a decade ago. "Good news! They were producing way too many of those." That's what I thought (and still think). The problem is that, apparently, pre-modern history is in free fall. The few academic history positions that remain are almost exclusively for the post-1500 (and mostly post-1800) period. And the graduate students are overwhelmingly in modern history. Give it a generation, and most major universities won't have anyone with any serious expertise in anything older than a couple of centuries.

[Mind you, I'm not a historian or anything remotely related. This is just something I read about on the Internet. Our host may know more.]