Prof. Smajdor: 'Is pregnancy a disease?'

Breaching yet another bunch of frontiers (sanity, research ethics), 'the Science™' now muses about the foundation of the human condition--if you thought you hate academia enough already, think again

Yesterday we met Anna Smajdor, a professor of practical philosophy and misanthrope if there ever was one. Today, we’ll explore a bit more of her sick and twisted mind by engaging with her most recent brain-child, an ‘original research’ article that just appeared in the Journal of Medical Ethics (sic).

Entitled, ‘Is pregnancy a disease? A normative approach’, researchers Anna Smajdor (U Oslo; faculty profile) and Joona Räsänen (U Turku; faculty profile) boldly breach the frontiers of sanity, woke-ism, and, yes, nature.

I’ll merely add that while I’ve read a lot of batshit crazy papers in my life, the stuff that these two people put out is marvellously insane; at the same time, I freely admit that reading these papers is taking a toll—I’m honestly unsure if what they write is meant sincerely or if people like Smajdor, Räsänen, and their ilk are trolling everybody, and doing that masterfully.

For now, I’ll delimit myself to taking them as serious as I’d other academics; I’ve added some commentary and [snark], but otherwise all quotes are from that paper.

‘Enjoy’, if you will.

From the Introduction to ‘Is pregnancy a disease?’

Imagine a patient who visits the doctor having an abdominal mass that is increasing in size, causing pain, vomiting and displacement of other internal organs. Tests are booked, and investigations are planned. But when the patient mentions that she has missed her period, these alarming symptoms suddenly become trivial. She is pregnant! [I’m going out on a limb here as a man, but I’m certain Prof. Smajdor has never been pregnant]. No disease, nothing to worry about. But is this the right way to think about things?

What counts as a disease is a recurring question in philosophy of medicine. Experts disagree about the criteria by which we can distinguish diseases from other phenomena.1 Some believe that diseases can be defined with reference to some objective truth, others that the term is purely or partly socially constructed [which is why medicine is both an art and a science]. Whichever view one takes, it is difficult to find a theory that accommodates all those conditions we take, intuitively, to be diseases, while excluding all those that, intuitively, we do not. We argue that there are several pragmatic reasons—based on a combination of biological, social and normative considerations—to classify pregnancy as a disease.

I’ll briefly interrupt the flow here to explain what Smajdor and Räsänen are doing here: they are applying the dialectical method as devised by Kant, Hegel, and Marx to this issue.

Basically, the dialectic works like a wedge, marrying a truth (biological considerations) to one or more lies (social and normative considerations) to move any debate to the proverbial ‘next level’. It’s a classic word-game whereby you take a word, imbue it with additional meaning serving your purposes, and make those not in your little club adopt your point by accepting whatever insane proposition you’re making (e.g., ‘Trans-women are women’). That’s how these insane revolutionaries are making the majority of people move towards their aims.

‘Harmful symptoms’, as related by the authors

Diseases are harmful. They cause suffering and are bad for the health of the person who experiences them. Commonly, though, in a wanted pregnancy, we focus on the longed-for child rather than whatever harms the pregnant woman may experience. The risks of pregnancy may appear negligible or insignificant in this context. The harms of pregnancy are often transient, and most pregnant women survive the experience. Fear of becoming pregnant is in itself regarded as a pathological condition—‘tokaphobia’—that may require medical treatment.2…

Two questions emerge here. First, how do the risks of pregnancy compare with those of other conditions that are regarded as bona fide [sic] diseases? And second, are health risks themselves a sufficient basis on which to designate a condition as a disease?

That latter aspect is even more insidious than the former, I’d point out, as the mere possibility of contracting a disease has been weaponised during the Covid ‘Pandemic™’ to get people to do all kinds of stupid and harmful shit, incl. masking, social distancing, and ‘even’ the modRNA injections count among these measures.

To answer the first question, we can compare pregnancy with measles. Measles is uncontroversially regarded as a disease and treated as such by public health authorities and health professionals. Measles is harmful to nearly all of those who catch it. However, most patients will survive. Very few will die, and only a small proportion will go on to experience longer term impacts on their health. So how do the risks of pregnancy compare against those of measles?

And this is how these insane people draw you into their witch’s circle: come up with whatever idea and ‘compare’ is to something that is uncontroversial. And before you know it, you’re thinking ‘well, there’s a point, however strange it might sound, but that’s a legit issue’. It is not.

It’s also entirely made up, as you could, by the same ‘logic™’, also compare anything (e.g., pregnancy) to anything else (e.g., driving a car) and come up with the same conclusion: ‘like driving, pregnancy carries the statistical odds of XZY of dying, hence we should forbid pregnant women from driving’. See how easy that sleight of hand argument is?

Like measles, pregnancy is a self-limiting condition [need a comment? pregnancy is not a pathogenic illness that both boys and girls may contract; put differently, it’s something that can’t be compared]. It follows a predictable trajectory that usually ends in the patient’s recovery. Both pregnancy and measles also involve symptoms that can impair one’s normal functional ability [again, this is batshit crazy stuff because pregnancy, for whatever reason and irrespective of one’s opinions, is a normal biological function among the vast majority of complex life forms on earth]. Common symptoms experienced during pregnancy include: back pain, bleeding gums, headaches, heartburn and indigestion, leaking from the nipples, nosebleeds, pelvic pain, piles, stomach pain, stretch marks, swollen ankles, feet and fingers, tiredness and sleep problems, thrush, vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, vomiting, morning sickness and weight gain.4 Like many diseases, including measles, pregnancy is a condition that has distinct stages.5 The first stage of pregnancy commonly involves many of the symptoms described above [here the authors reveal their ignorance, whether acquired or for argumentative purposes, and ignore that pregnancy is conventionally divided into trimesters]. The second stage—labour—will usually involve extreme pain, powerful cramps, and the ripping, stretching and damaging of tissue [doesn’t happen in all pregnancies, esp. if a mother has more than one child]. This second stage is far riskier than the first, in terms of long-term threats to life and health [for who, you narcissistic morons?; the first trimester is ‘far riskier’ for the developing infant; and, yes, life is risky from birth onwards, which is also a biological fact].6

While painful to read, let’s not forget that parthenogenesis is a naturally occurring phenomenon that ‘occurs naturally in some plants, algae, invertebrate animal species (including nematodes, some tardigrades, water fleas, some scorpions, aphids, some mites, some bees, some Phasmatodea, and parasitic wasps), and a few vertebrates, such as some fish, amphibians, and reptiles’.

As much as the authors might wish to parthenogenesis to emerge among higher mammals, including humans, that ain’t how nature works.

What about mortality rates? Here, we can compare the lifetime risk of dying from measles with the lifetime risk of dying from pregancy-related harms. The WHO states ‘A woman’s lifetime risk of maternal death is the probability that a 15-year-old woman will eventually die from a maternal cause. In high income countries, this is 1 in 5400, vs 1 in 45 in low-income countries.’7

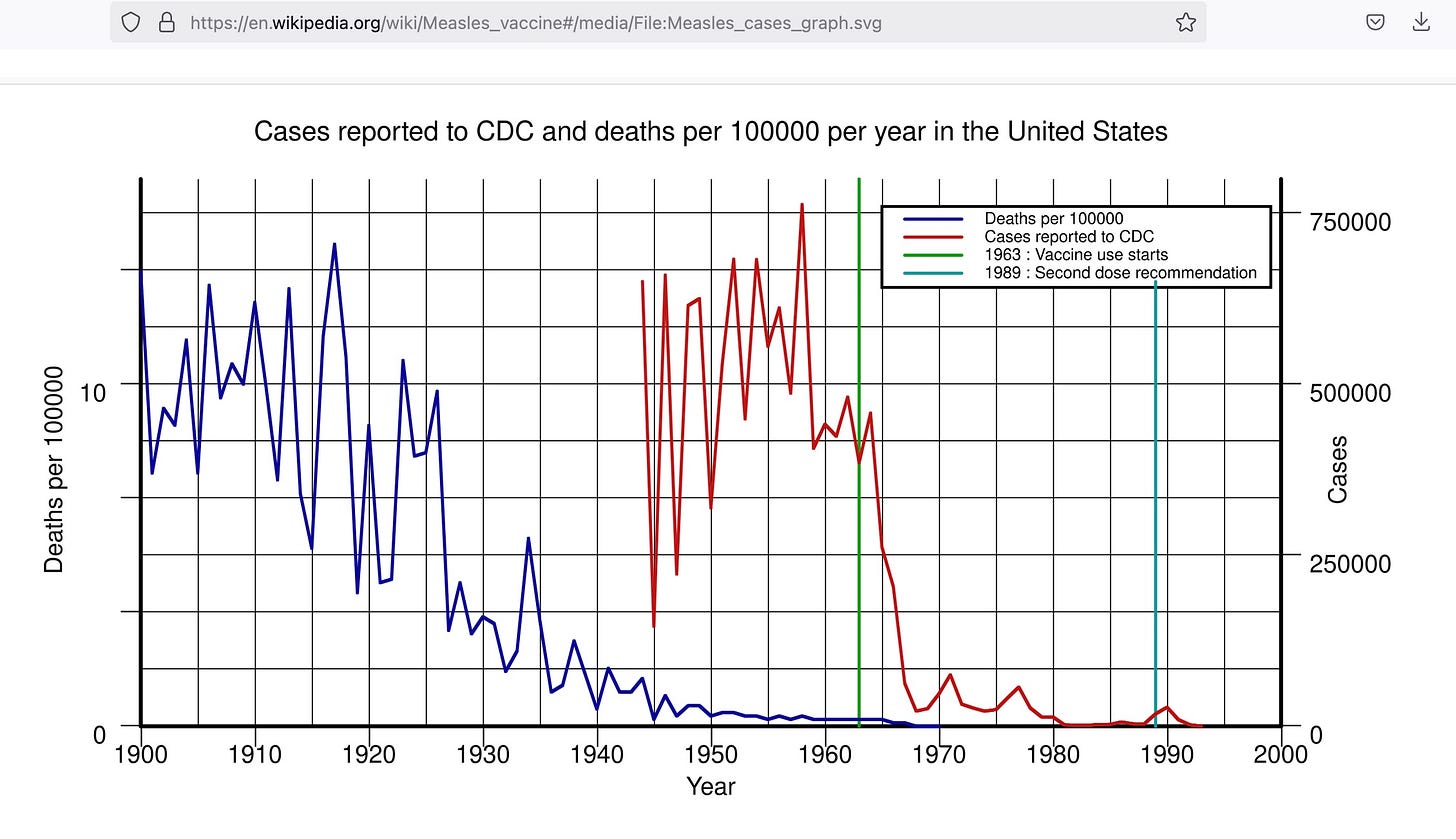

The risk of dying should one catch measles is around 1 in 5000. However, the lifetime risk of dying from measles is not simply 1 in 5000—it is far less than this, largely because vaccination programmes have diminished the likelihood of contracting measles during one’s lifetime. The incidence of measles has diminished in the USA, for example, to less than one per million.8 Of these one per million who contract measles, only 1 in 5000 will die. Thus, the lifetime risk of dying from measles in a country with an effective vaccination programme is 1 in 5000×1 000 000. The same source notes that prior to vaccination, almost everyone would expect to be infected with measles at some point during their lifetime. In this case, the lifetime risk of dying from measles would be more or less identical with the 1 in 5000 chance of dying should one catch measles, since catching it becomes almost a certainty.

Two things: the comparison is extremely misleading, but since it involves some generic pro-vaxx lingo, it passed peer-review (I presume). I’m not addressing the adventurous (ab)use of mathematics here. Note that the authors casually argue that infection with measles equals chance of dying of measles, which is misleading massively (and not an argument).

Anything that involves public health measures that doesn’t include sanitation and indoor plumbing, as well as electricity connections, is a moron.

As the compilation clearly shows, deaths from measles per 100,000 people fell to close to zero some ±15 years (late 1940s) before the first measles vaccine was adopted (in 1963).

The comparison is also off on a second level, by the way, and that’s the comparison of presumed ‘life-time risks’ of contracting measles vs. pregnancy: while the former is possible, carrying a child to term is a time-sensitive matter and typically quite impossible outside the 14-51 years of age time window. Talk about comparing apples and oranges (or flowers and bees).

I’d offer a third notion here, too: think about driving once more—you’d probably assume that those young people (18-24) who just got their driver’s licence are the most dangerous drivers—well, turns out that, according to this helpful piece in Forbes (US data from 2022), the most dangerous age bracket is 25-44, which saw the highest number of killed people at a rate more than twice as high as the 15-24 age bracket.

Now, if you’d like to make a BS argument à la woke, you’d invoke what is called ‘intersectionality’ and note the ‘unfair-ness’ and ‘systematic discrimination’ of people in the 25-44 age cohort, in particular if they are (add variables, e.g.) ‘pregnant people’ (Smajdor and Räsänen): just imagine the lifetime-risk of dying in a car accident if you’re pregnant…this is, of course, insane, batshit crazy, and totally misleading—and this is exactly what Smajdor and Räsänen are doing.

On this basis, the lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy-related causes is dramatically higher than the lifetime risk of dying from measles in countries with a vaccination programme.

This claim is so outrageously stupid and misleading at the same time, it boggles the mind and makes me marvel at the reviewers of this ‘paper™’.

This is true despite the fact that those countries are also likely to be the ones that have effective maternity health services. If we compare the risks of pregnancy in countries without such services with the risks of measles in countries without vaccination programmes, the picture is even starker [this is a secondary, equally misleading farce]. The lifetime risk of dying in childbirth in low-income countries is 1 in 45 [remember that the authors talk about ‘pregnancy’, not ‘childbirth’].7 And the lifetime risk of dying from measles would approach 1 in 5000. With or without effective health services, the lifetime risk of dying of childbirth significantly outweighs that of dying from measles.

That’s painful, eh? Note that the last sentence is a claim unsupported by evidence offered by Smajdor and Räsänen, but then again, they’re so far beyond, it doesn’t matter, I suppose.

However, unlike measles, pregnancy is a condition that affects only a certain group of people [they appear to have noted it’s a stupid thing to compare an infectious disease with pregnancy]: those with female reproductive organs. Perhaps this partly explains why the risks involved in pregnancy are higher in places where women’s rights and independence receive less social and legal protection [that’s a fair point, but it’s also another diversion is that describes the entire world until, say, some 150-odd years ago—this is why history must be memory-holed lest someone notices that patent absurdity of such claims; on a secondary plane, not all cultures/countries are equal, and not all societies are equally conducive to human flourishing (Mr. Trump once called these ‘shitholes’, and it’s kinda hard to argue with him on that one)].

If medical services are not available, many pregnant people [see how easy and conveniently these clowns move from ‘those with female reproductive organs’ are affected to woke nonsense] will be seriously injured as a result of second-stage pregnancy [meant is labour], and a significant number of them will die…

However, many people do not regard pregnancy as a disease; indeed, the idea that it might be thus construed is highly contentious [tell me more, please, please, please].9 10 If pregnancy is not a disease despite its risks, then there must be some additional factor to take into account. One such consideration might be the degree to which the condition is valued.

‘The Science™’, very hard at work at ‘splainin’ something that doesn’t require ‘splainin’, if you can believe it.

I’ll summarise the subsequent sections for you, but I suggest you read them in their entirety (that is, if you feel like banging your head against the wall).

On the ‘Value’ of Pregnancy

Pregnancy is often a cause for celebration. It can give people’s lives meaning, and is a source of intense fulfilment and profound significance for many individuals. Pregnant women are popularly said to be ‘blooming’. Nevertheless, as Iris Marion Young points out, those who are privileged enough to regard pregnancy as a choice are in a minority. For most of the world’s inhabitants, there is nothing voluntary about pregnancy, and women may be very far from celebrating each pregnancy they experience.10

Unlike measles, pregnancy is a condition about which people may take a variety of views. One may be dismayed or overjoyed to be pregnant. These subjective responses might seem to disqualify pregnancy from being classified as a disease. Typically, people think of the classification of disease as being an objective, scientific endeavour, but some philosophers hold that it is primarily a matter of value.

So, basically, the authors claim not everyone is universally of the same opinion about pregnancy, which makes it hard to classify it ‘objectively’. And then they merely add: ‘we think differently’, and off to the races they go.

The entire farcical nature of doing so is revealed in the following paragraph:

A person who is happy to be pregnant may welcome even unpleasant symptoms such as stretch marks and nausea. The pain of childbirth may be treated as a badge of honour. Perhaps then, the ‘badness’ component of pregnancy can simply be disregarded in such cases. If so, a wanted pregnancy is not a disease, whatever its impact on a person’s health. However, for consistency, this might imply that in other cases where a person finds value in their experience, they can no longer claim to have a disease [just re-read this sentence, think of ‘gender-affirming surgery’, and run with your thoughts; there’s nothing consistent in this statement (other than, perhaps, mental illness masquerading as ‘science™’), and once applied to other aspects of the woke mind virus—think: ‘sane-ism’ or ‘able-ism’, the entire charade is revealed for what it is: a scam]. There is a wealth of qualitative research showing that sufferers often ascribe value to their experience of conditions that are uncontroversially regarded as being diseases, such as cancer and heart disease [thus pregnancy is linked to both].12–15 If we then conclude that for such people their condition is no longer bad for them, and thus that they do not have a disease, this implies a very rigid and binary understanding of the relationship between subjective value and disease.

Well, you can either be pregnant or not; it’s impossible to be ‘a little bit’ pregnant, isn’t it? Same with cancer or heart disease. Or measles, for that matter. Undeterred by evidence and reality, Smajdor and Räsänen march on:

In reality, people’s subjective beliefs and values are not fixed in this binary way. Therefore, if values play a role in classifying disease, we should not expect this to yield a neat, reliable distinction between what constitutes a disease and what does not.

What ‘values’? Whose ‘values’? Do they—like identities—change over time or would they remain static for, e.g., someone of child-bearing age vs. a woman after menopause?

Hence, it won’t surprise you that what Smajdor and Räsänen actually set out to do—has very little to do with pregnancy or the human condition:

We suggest that it is vital to think carefully about the social conditions that inform a patient’s perception of [pregnancy], before endorsing too eagerly the idea that subjective value is what makes [pregnancy] a disease or not.

In other words: they show, tucked away in lots of stupid word games, that they admit they’re not doing much more than that. By that time, if you didn’t pay attention, though, you’re so firmly in their witch’s circle that you have to play by their rules.

There are occasions where conditions are actively sought, in circumstances where one might feel lucky to have caught them, and where this does not intuitively challenge their disease status. Some common diseases, such as chickenpox and measles used to be regarded in this way [oh, look, their prime comparator, measles, is relativised in this way now].16 To draw on a more recent example, many people who contracted the milder omicron version of COVID-19, after having been fully vaccinated, felt themselves fortunate to have done so [well, that’s particularly hare-brained as all that this sentence does is re-affirming the insane believe in the modRNA poison/death juices; also, it’s a contradictory, if not circular, argument].17 Another example might be that of courting disease in order to escape the draft.18

If you thought it couldn’t get more stupid, well, what can I add?

It might be objected here that some women specifically want to experience pregnancy as part of what is entailed by motherhood. They do not regard pregnancy as the lesser of two evils, but as a valuable experience in its own right. However, as long as pregnancy is the only route to reproduction for most women, it is difficult, if not impossible, to gauge the value of pregnancy in its own right [hence yesterday’s posting about ‘zombie pregnancies’ offering a way out of this conundrum]. To push this further, one might consider how doctors or friends and family ought to respond to someone who became pregnant purely in order to experience pregnancy, without any intention of parenting the child, and independently of any additional motive, such as wanting to facilitate the parental wishes of others, via surrogacy. We suggest that in such a case a person’s wish to be pregnant might seem pathological.

Hard to argue with that notion, but then again, this is probably better classified as a form of mental illness.

Notes on ‘Medical Practice’

Speaking of mental illness, here’s what the authors say about that:

Although pregnancy is not formally classified as a disease per se in modern medical practice, in many ways it is treated as such [it’s all in your head]. Preventive medicine employs a variety of methods to stop pregnancy from occurring, including the provision of condoms, prescription of hormonal birth control pills, insertion of intrauterine devices, injection of hormonal contraception, and surgical removal or restriction of the reproductive organs. In cases where pregnancy has already occurred, abortion may be regarded as a form of medical treatment that aims to ‘cure’ the condition by preventing it from progressing to the more aggressive second stage. In this sense, the avoidance of pregnancy is a fairly routine and unexceptional aspect of medical practice in jurisdictions where contraception and abortion are available.

A bit further below, what are arguably major advances are considered in the following, quite negative ways:

In cases where pregnancy is wanted, or where contraception and abortion are not available, pregnancy is still the focus of considerable medical attention and intervention. Pregnant women are expected to attend clinics or hospitals as a matter of course in order to facilitate medical surveillance…

It is commonly regarded as a matter of urgency to ensure that a birthing woman has access to medical care. Interventions of various degrees of invasiveness may be employed: forceps and other mechanical aids, drugs, surgical removal of the baby. Pregnant women who refuse medical interventions deemed necessary for their baby’s health are commonly regarded as immoral or irrational [speak for yourselves]…

After the birth, most women will need time to recover from the immediate effects of the delivery. Many will experience ongoing, perhaps lifelong complications, requiring further medical interventions; surgical repair of prolapse, for example, or treatment for incontinence.

So, there you have it. There is not a shred of data, let alone references, to support these assertions. At this point, I suppose we can be pretty certain that Prof. Smajdor may not have experienced pregnancy; I reserve judgement, of course, about her male co-author Räsänen…(/sarcasm)

Note that they listed a bunch of things, and here’s the main ‘argument’ they advance:

Thus, if [this is a hypothetical] we define a disease simply as something that medicine regards as an appropriate target for attention and/or intervention, it seems that pregnancy is indeed treated as a disease, even though it is not explicitly classified as such.

Once again, these woke-fied people take something that exists (their ‘thesis’, if you like), add something that sounds plausible—‘appropriate target for attention’ (an ‘antithesis’)—to arrive at their ‘synthetic’ desired outcome: classification of pregnancy as a disease.

If the fetus is at risk (and some aspects of medical treatment seem to suggest that being in a uterus is in itself a situation of inherent risk),25 health professionals find it much easier to move into disease mode, whereby the fetus’ location in the woman’s body becomes pathological. In short, pregnancy is in some respects treated like a disease that threatens the fetus’ health, and to a lesser extent like a disease that threatens the woman’s health.

At that point, we may ask a few salient questions: is the fetus a human being? Would life begin at conception? (I believe that to be the case.)

The most patently absurd notion—and, let’s not mince words here, this is how these insane revolutionaries advance their agenda—is the assertion that, under certain conditions, pregnancy already is a pathological condition (i.e., if the life of mother and/or unborn child are at-risk), and the single ‘innovation™’ of Smajdor and Räsänen is this: to take some admittedly existing, if rare, complications and project it to all pregnancies.

Basically, this is the same argument that was (is) employed by abortion advocates: in the rare case of unwanted pregnancies resulting from rape, abortion should be considered (that was the original argument). Look at where we are now—just look for the term ‘late-term abortion’ or, even more disgustingly, take Giubilini and Minerva’s 2013 ‘paper™’ (which appeared in the very same Journal of Medical Ethics, by the way) entitled ‘After-birth abortion: why should the baby live?’.

This is how ‘far™’ we’ve come: the normalisation of infanticide and the pathologising of eminently natural, if not entirely convenient, parts of the human condition, such as pregnancy.

Misunderstanding even the most basic aspects, Smajdor and Räsänen then mumble on:

In the context of fertility treatment, an otherwise healthy body is subjected to a range of painful and invasive medical interventions, in order to bring about a condition that causes all the risks and symptoms described in our first section above.26 Another potentially counterintuitive example is that of elective vasectomy. Effectively, this treats male fertility as a disease.

It’s possible to see it that way, albeit at this point, I’d argue that these clowns have missed the point entirely.

To showcase their musings, this is how they try to wrap this section up:

What we are willing to consider disease is influenced by historically and culturally relative values. Conditions such as ‘drapetomania’ and ‘hysteria’ were once classified as diseases.27 Homosexuality was treated as a disease up to fairly recently in orthodox western medicine. Now we know better.

Moral relativism is a mental illness, by the way. If you didn’t see it that way, here are two more examples the authors offer to support their case:

Drapetomania, for example, was a condition that affected slaves in the slave-owning parts of the USA. Its main symptom was a compulsion to run away, which was unamenable to any threats of punishment [oh, look, humans do things even if it might bring pain or death—it’s a bit like pregnancy, isn’t it?]. In the context of a slave-owning society, this phenomenon was regarded as a bona fide disease. Likewise, homosexuality is not a mere figment of the imagination. It is plausible that heterosexual people are biologically different in some way from gay people [maybe, maybe not, but being gay is very much at-odds with getting pregnant…]. But societies’ categorisation of this difference as a disease reflected a moral conviction—that it is wrong to be gay.

I’ll just add here that it was Christianity that served as the moral foundation for the abolishment of slavery—not once but twice (once in late Antiquity and the other time around 1800). No need to let such inconvenient historical facts dispute one’s made-up BS ‘argument™’, though.

Pregnancy as ‘Dysfunction’

There’s also another absurd section about pregnancy as ‘dysfunction’, and I’ll restrict myself to the choicest, most stupid quotes—and I’ll introduce this section by pointing to a very simple fact: looking around nature, we notice that ‘even’ creatures without a central nervous system are able to determine that male and female sexes are relevant for procreation. Jus’ sayin’.

We have shown that pregnancy is harmful (like measles). Like measles, pregnancy is also caused by an externally originating organism that enters the body and causes the harmful results we have described. Accordingly, on this view, sperm could be seen as a pathogen in the same way that the measles virus is. Measles and pregnancy can also be medically treated, prevented, cured or managed. Measles is more likely to be viewed as a misfortune, while (a wanted) pregnancy may be a cause for rejoicing, but as we have suggested, this is not a sufficient basis on which to make a robust distinction between the two in terms of their disease status.

Do we really need more evidence of the weird, sick, and twisted minds of the two authors?

There is an important common-sense difference between pregnancy and measles [no shit analyses, Sherlock & Watson]. Measles is a problem: an indication that something has gone wrong…

Measles is dysfunctional. In contrast, it is commonly regarded as a mark of a healthy body that it can become pregnant…

This, after all, is why philosophers such as Cooper and others, look for an account of disease that does not rely on ideas of how an organism ought to function.

In other words, the authors do admit that their ‘science™’ has firmly left reality.

I’ll do one more paragraph here because it reveals, for anyone who’s still reading this BS, the intellectual vacuity of ‘woke’ and the stunningly stupid ‘arguments’ employed by its practitioners:

When something is dysfunctional, it is performing wrongly; it is not behaving in accordance with the intention of the designer [so that indicates we humans were designed—by God, perhaps?]. But this seems to presuppose that there is a right way to perform, or a design, and that this design is perceptible to us [ah, of course we must ‘criticise’ this notion as soon as it appears; as an aside, let’s note that if humans can perceive these (and don’t require a ‘designer’), we might become God—it’s one of the hallmarks of the gnostic cult deriving from Kant, Hegel, and Marx, which we commonly refer to as ‘socialism’]. In other words, this is a way of understanding disease that seeks to base its classifications in objective facts about how an organism should behave [see, it’s wrong to observe facts and derive ‘laws’ from it]. But the concept of healthy functioning itself demands a normative evaluation. It goes beyond being merely descriptive [this is where Smajdor and Räsänen depart the scientific method]. In contrast with Cooper’s subjective approach, the evaluative element is baked in at a far removed level from the lived experience of the sufferer [no need to trust a pregnant woman’s experiences (this is so hilariously contradictory to, say, all BLM and ‘white supremacy’ stuff)]. Instead, experts make these judgements, and patients and practitioners accept them and act accordingly [I’ve almost fallen off my chair reading this sentence]. It is fundamentally elitist [sayeth Smajdor and Räsänen in a refereed academic (?) journal: don’t you have any sense of irony or shame?]…

The question of what constitutes good functioning is not obviously one that we can divine simply from observing the behaviour of an organism, or studying biology or chemistry, or from theorising about these phenomena [so, science is wrong]. The notion of proper functioning borrows from a teleological view of biological organisms, or alternatively, from the belief that there is indeed a designer [I struggle to understand what they are saying]…That our bodies work in a particular way is not an indication of how they ‘should’ be, but is simply an indication that at some point in our past, these traits were not incompatible with our ongoing survival in the environments we inhabited [this is so bizarre, it boggles the mind].

I’m in pain now reading this, and I’m sorry you read that, too.

The concept of ‘normal species function’ has been used by some writers in order to distinguish what should or should not be classified as disease.30 We tend to think of pregnancy as a normal aspect of human life in a way that measles, for example, is not. But what does ‘normal species function’ really mean here? [sigh]

Pregnancy is not normal for men, nor girls under 11 or women over 51. But what if we narrow down to consider only those of ‘reproductive age’, that is, 15–49?3 Is pregnancy normal for this group? Currently, there are approximately 1.8 billion such women in existence.32 But there are only around 211 million pregnancies yearly.33 Thus, the norm for people in this group is not to be pregnant. Based purely on numbers, pregnancy is abnormal, even within the narrowest target group we can define. So can we really insist that pregnancy constitutes ‘normal species function’ when most of the people in the target group are not pregnant?

Sigh. It takes 9-10 months to carry a child to term, to say nothing about the time it takes to get pregnant and to ‘recover’ from pregnancy.

None of these considerations play any role here, as they would probably go a long way towards ‘splainin’ to the authors why pregnancy is as ‘rare’ as it is. Once one factors in education, career choices, economic constraints, and, say, survival of both mother and child(ren), these notions are easily explainable—but our intrepid philosophers don’t care. It would ruin their nice little ‘theory™’.

I’m skipping the sections of Boorse’s biostatistics and ‘infertility as a disease’ (the latter is Räsänen’s main research focus these days, hence I suppose this is why it’s in the article)

Authors’ Conclusions (finally)

Conclusion

We have argued that there are pragmatic grounds for classifying pregnancy as a disease on the basis that it shares important features with other diseases, such as measles [that’s stupid—to learn why, we don’t consider a trailer a car ‘on the basis that it shares important features with other things’, such as cars; the same goes for assumptions of the equivalence of, say, spines in fish, birds, and mammals]. To be pregnant is to experience symptoms and face significant risks to life and health. We acknowledge that on accounts such as Boorse’s [uses stats, hence they must disagree on this one], pregnancy is not obviously a disease, but we note that such accounts seem to open further problematic questions about the relationship between pregnancy, evolution and species survival [well, no pregnancies, no species survival—there’s an easy solution here, you know…but perhaps (obviously) Smajdor and Räsänen don’t know…]. We suggest that it is possible to find value in the experience of disease, and that therefore to classify of pregnancy as a disease does not preclude the possibility of its being valuable to those who experience it [in the most charitable way, this is circular reasoning with the envisioned result being presupposed by the premise: classic dialectic hogwash]. Likewise, although we acknowledge the risks of medicalisation, we emphasise the point that pregnancy is already heavily medicalised, but in ways that simultaneously tend to deprive women of patient status, thus increasing their vulnerability in the medical system [I don’t know what they mean by this].

As things currently stand, caesarean section is one of the most common medical interventions45 and one of the most common reason for hospitalisation in modern societies is childbirth.46 [obviously, the material interests of hospitals—based on data from Switzerland, C-sections are billed at 3-4 times the costs of natural births, hence hospitals have a bunch of incentives of ‘requiring’ them—are never considered as it would ruin this mai conclusion] Yet maternity services are often underfunded [where, by whom? Specifics are relevant, and we’re not given any but blanket assertions—classic grievance BS]. Women report terrible experiences while giving birth, and at the same time, heavy pressure to become pregnant. We conclude that, as Kukla has shown in the context of infertility, the classification of something as either disease or not disease has profound normative implications [no shit analysis]. While classifying pregnancy as a disease comes with some risks, we suggest that a failure to recognise and respond to its disease-like features is likewise problematic, and puts many pregnant people at increased risk, as well as serving to reinforce and entrench social pressures on women in particular [go ahead, re-read that sentence: it’s mind-bending].

Finally.

If you’re up for it, there are comments—like the one by Colgrove and Rodger who hold the following:

They cannot establish that pregnancy is a disease, only that plausible accounts of disease suggest this. Some readers will dismiss Smajdor and Räsänen’s claims as counterintuitive. By analogy, if a mathematical proof concludes ‘2+2=5’, readers will know—without investigation—that an error occurred.

Hilariously, in their reply, Smajdor and Räsänen hold the following:

We claim that our critics assume what needs to be argued that the primary function of our sexual organs is to reproduce. Since only a small percentage of sexual intercourse leads to pregnancy, it is far from obvious that reproduction is the primary biological function of our sexual organs [what would their primary function be then?] We also claim that while taking pregnancy itself as a reference class could avoid the conclusion that pregnancy is a disease, the strategy is problematic since it renders the Boorsean approach to disease and health circular and effectively deprives it of any utility in determining whether a particular phenomenon is a disease or not.

Basically, they say we disagree as acceding to their critics’ arguments would render their article moot. Who would have thought that Smajdor and Räsänen would sink that low? (/sarcasm)

Bottom Lines

These authors are taxpayer-funded: Smajdor is an employee at the U of Oslo and her colleague Räsänen works at the U of Helsinki.

I’m not claiming my own field (history) provides many more services to society at-large, but I will state this: at least I’m not engaging in active subversion of the existing biological order.

That said, the main beef I have with woke nonsense like the BS put out by Smajdor and Räsänen is—that this article is written in a poor style, argues nonsensically (and partially contradictorily), and that this passes for ‘Science™’ these days.

The university, one of the crowning achievements of mediaeval Christendom, is quickly becoming a cesspool of vanity, mediocrity, and irresponsibility that, because it’s coupled with there being no consequences (‘hey, we’re doing science here’), it merely breeds lunatics who claim the white coat of respectability.

It’s a very sad development, esp. in light of the fact that I firmly believe that the university has a role to play in society; I also hold that not everyone who works or studies at a university is totally useless and amoral, but I do think that people like Anna Smajdor, Joona Räsänen, and their ilk are.

I sincerely hope that, after a significant downsizing of higher education, that the university will continue to improve the human condition, even though that will likely require a lot of pain before we get there.

I’ve outlined the bumpy road ahead almost three years ago, and I suppose that piece has aged quite well:

Take a deep breath if you made it until here. Chop some wood, if needed, to calm down. And do share these ‘ideas™’ widely so more people may wake up and fight this insane mind virus.

It can only be transmitted by men. Quarantine the bastards!

I couldn’t push myself to read this to the end. I detect mental disease.