Today’s posting comes in two parts: first, a glorious piece on NATO chieftain Jens Stoltenberg, which appeared in NRK on 23 Feb. 2023. In this piece, Stoltenberg all but ‘promises’ that which happened in Ukraine will, eventually, occur in East Asia, too. Now, I don’t have a crystal ball to judge whether or not Stoltenberg is saying the truth (ahem), but questions about his ‘prophecies’ are, I’d argue, in order.

The second part is a long-ish op-ed composed by Sigurd Falkenberg Mikkelsen, the Moscow-based foreign correspondent of Norwegian state-broadcaster NRK. This piece appeared today, on the occasion of the—roughly nine-year—anniversary of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine.

The below picture is a kind of ‘where is the University of Bergen?’ quest for you, my dear readers. UiB will host an international conference today, entitled, ‘War against Ukraine: Accountability and Responses’, whose guests include, among others, Norwegian PM Støre and Liliia Honcharevych, Charge d’affaires of the Ukrainian Embassy in Norway. On that page, there’s also a link to a livestream, if you’d care to watch this event; it’ll kick-off at 10 a.m. Norwegian time.

As always, translations and emphases are mine, as are the bottom lines.

‘A willingness to sacrifice soldiers that is frightening, bloody and cruel’

One year after the invasion, Jens Stoltenberg is horrified by the brutality of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

‘It’s been a while since I’ve walked here now. I’ve been travelling so much.’ Jens Stoltenberg strolls along a wide path in Brussels’ Bois de la Cambre, the park where he relaxes whenever he can.

The NATO Secretary General has been living with the war for a year. Behind him is a week filled with defence ministers in Brussels, talks with Turkey's president in Ankara, and meetings with all manner of security officials in Munich.

‘This park is my most important…it’s my little Nordmarka [Oslo’s northern ward, a popular recreational area].

NATO’s No

We’ll come back to the Nordmarka issue in a moment. There are more important things for Stoltenberg. The most important thing he can do in his life is to lead NATO in this phase, he said the last time he agreed to another round of extensions as Secretary General.

That was just over a year ago now. A year that has changed the world for good. When Stoltenberg sums up this period, there is an event at the very beginning of the war that stands out among the most significant for him:

There have been so many terrible moments, it’s hard to point to one in particular. But the one that really impressed me personally was the conversation I had with President Zelensky very shortly after the invasion, where he asked NATO for a no-fly zone to prevent all the Russian attacks.

NATO countries could not meet that request.

‘Zelensky is a person I have worked with and met several times before the invasion. I still find it painful to say no to that’, Stoltenberg said. ‘But it is an expression of the balancing act we have to do: support Ukraine, but prevent a full-scale war between NATO and Russia.’

Balancing Act

That balancing act is also reflected in the type of weapons being sent. ‘We will give Ukraine what it needs to win this war’, Stoltenberg has said several times in recent weeks. But it takes time.

And once it has been decided that the key to peace is to enable the Ukrainians to repel Russian attacks, the wait can seem too long.

[NRK] Do you get frustrated by the long discussions within NATO countries about what kind of weapons to send and when? Could this have been done more quickly?

[Stoltenberg] I think it is futile to discuss whether something could have been done faster or earlier. Everybody has to understand that this is a new and dangerous situation. We must coordinate and be responsible in the decisions we make.

Now we have to look forward. What is happening now is an enormous mobilisation to bring in more ammunition and more weapons, but not least to increase our own production. Ukraine’s current consumption of ammunition is significantly greater than our production capacity. That says something about the scale of this war. [or the failure of adequate planning on part of NATO…]

Back to the Trenches

Recently, several people, including among Zelensky’s associates, have compared what is now happening in eastern Ukraine to the trench warfare of the First World War. Stoltenberg believes the parallel makes sense.

Yes, it does. The Russians are throwing waves of soldiers against defence lines. Often it is former prisoners who are enlisted. They throw them forward, knowing that they are going to take very heavy losses. And then send the best soldiers afterwards, to gain some ground.

[NRK] Are there any limits to how many inexperienced soldiers Putin is willing to sacrifice?

It hardly seems so. There is a brutality, a willingness to sacrifice own soldiers that is frightening, bloody, brutal, and cruel.

The Russian armed forces have low morale, poor quality equipment and poor logistics. But they are many. And what they lack in quality, they make up for in quantity. That makes this war extra bloody. [talk about ‘Eastern hordes’, eh?]

Weapons and Negotiations

There is an ongoing debate in some European countries about whether arms aid to Ukraine should be accompanied by demands for negotiation. [watch out what follows]

‘This is a war that concerns everyone, so we have the right to discuss what the terms of a negotiation should be, not just wait until Ukraine says it wants to negotiate’, the famous German philosopher Jürgen Habermas has recently argued.

[as I wrote a couple of days ago, the visceral reaction Habermas’ essay received in German media is telling]

[Stoltenberg] This will probably end up in negotiations. But any signal that we are not fully committed to Ukraine reduces the chances of a peaceful solution. It is only when Putin realises that he will not win on the battlefield that we can hope for a negotiated solution.

With this in mind, the NATO Secretary General does not hold out much hope for the announced Chinese proposal for peace talks, which are expected this week:

China has little credibility to begin with. It is one of the few countries that has failed to condemn Putin's invasion of Ukraine. And it is a country that is increasingly cooperating with Russia. And there’s growing concern that China may be providing support to Russia. So we’ll see what's coming and assess it then.

[and that’s somehow not ‘racists’, coming from a white European man? /sarcasm]

Back to Nordmarka

[NRK] Has this year of war changed you in any way?

[Stoltenberg] Yes, it has. After the Cold War, many of us hoped it would be possible to have a cooperative relationship with Russia. That hope has disappeared.

I have no faith that it can be established with the regime we have in Moscow today.

This does not mean that Stoltenberg will talk about a hypothetical future in Russia after the fall of Vladimir Putin:

I am very cautious about making any statements about regime change in Moscow. That is not what is on NATO’s agenda. What is on our agenda is to support Ukraine. If Putin wins in Ukraine, it is a tragedy for the Ukrainians, but it is also dangerous for us.

Today’s walk in Brussels’ Nordmarka is at an end. Stoltenberg is moving on to other appointments. Where he is going in the autumn, he will not say much about.

[NRK] Will you be Secretary General of NATO when this war ends?

[Stoltenberg] I’m afraid I won’t be, because I’m afraid it’s going to last a long time. And I’m going to retire in the autumn.

[NRK] Will it be possible for you to say no, if everyone asks you to continue once more?

[Stoltenberg] I have made it clear that I will leave on the first of October, when my term ends.

A Changed World, by Sigurd Falkenberg Mikkelsen

The war in Ukraine has brought a new and profound seriousness to world politics and to our daily lives. Although the picture is bleak, some things have also turned out better than we might have expected.

Looking out on the Moscow River from inside the walls of the Kremlin leaves quite an impression. The history, the power, the bloody internal settlements and wars and invasions, somehow still speak to us from the newly refurbished walls.

Now Russia is again fighting a new great war, initiated and directed from inside these walls, with the aim of taking over a neighbouring country. [note that this is a hypothesis]

But Moscow does not look like a city at war today, at least not when I visited last November [so, this is ‘old news’ sold as something current]. The city has grown in recent decades, become more prosperous, and the war felt further away there than anywhere else I have been in Europe since the war began in earnest on 24 Feb 2022 [note that this isn’t what Stoltenberg had been saying as recently as last week: ‘it started…in 2014’]

Of course, that’s the way the authorities want it. It’s in the big cities, and Moscow in particular, that politics is decided. The less people notice the carnage in Ukraine, the better.

This will change when Western sanctions start to hit harder, when the war economy goes beyond the consumer economy, and when city boys come home from the front in coffins. [this is pollyannish, at best: the evidence about the Western sanctions is in: it’s the West, esp. European nations, that are bearing the brunt of them, not Russia]

There are no obvious solutions to the war in Ukraine.

It may well become a reality that the Russian authorities will have to deal with. Certainly, there was nothing in President Vladimir Putin’s speech to the people this week that pointed to peace. On social media, there are pictures of posters in the city that say ‘Russia's borders end nowhere’.

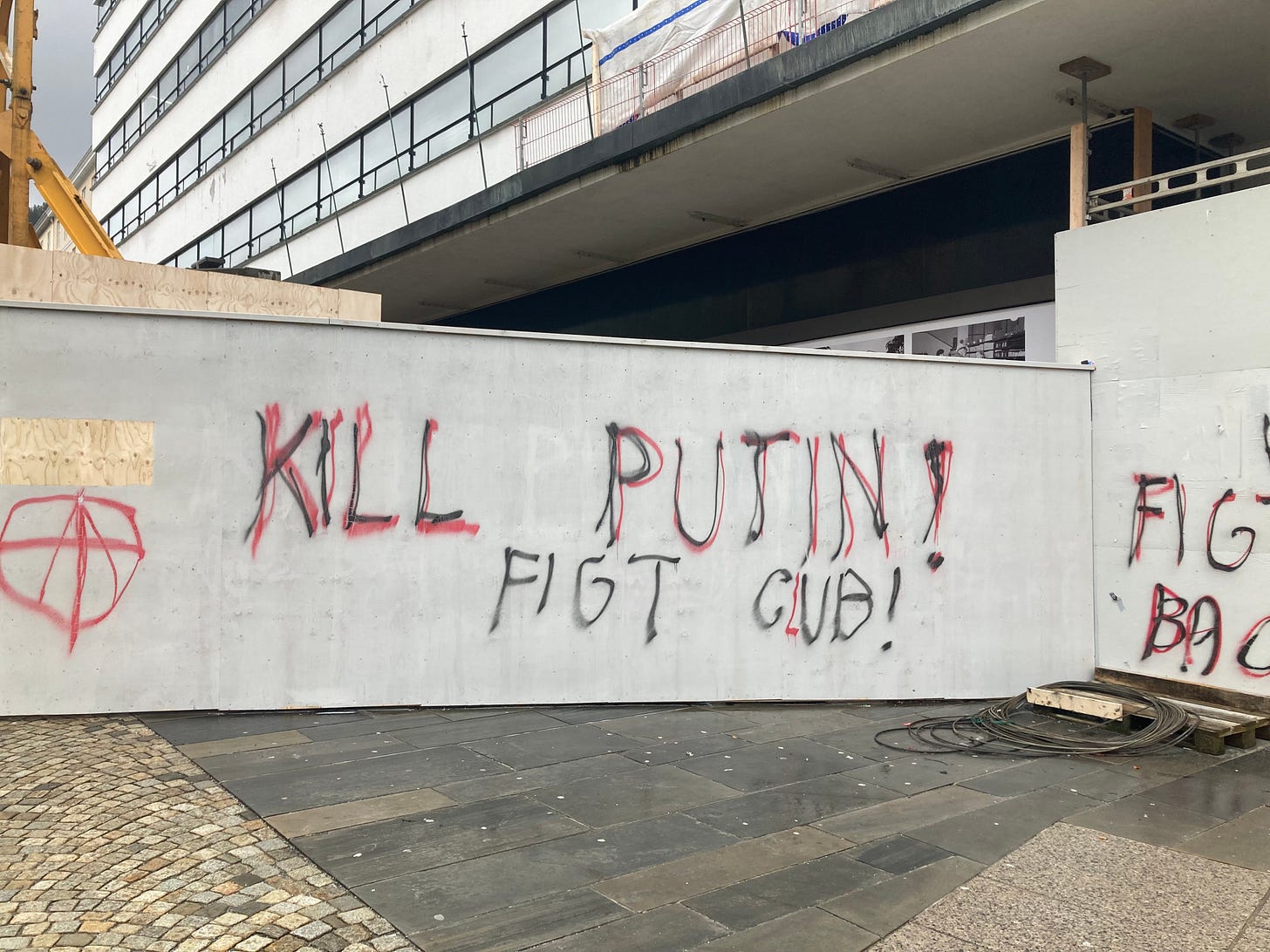

[here I’d like to show you what I’ve seen last week on the streets of Bergen:]

This goes to the heart of the conflict and explains why the war has shaken not only Ukraine but much of the world, even though the war did not start a year ago [oh, look at this: a gaffe?].

The annexation of Crimea and the intervention in the east happened in 2014, and since then Ukraine has been at war. It is easy to see in retrospect that Russia’s relationship with borders is flexible, at least as long as it benefits itself. Putin said so himself in 2016 with a smile during a geography quiz for children. [oh, c’mon on, leave out children as cheap props for your stunts, would you!]

But until last year, the world, albeit with protests and sanctions, allowed Russia to intervene and bully its neighbours, be it Georgia, Ukraine, or Belarus. It was part of the great power game of give and take. It is easy to see in retrospect that this was a mistake, but perhaps not so easy to see exactly what should have been done differently.

[this is an embarrassment to Mikkelsen: the 2008 Georgia operation came about in response to Georgian shelling, as the EU Parliament-funded report explained; as regards Belarus, well, they’re in a ‘union’ with Russia, and Mikkelsen’s consideration—‘the great power game’—is o.k., but the mixing with Ukraine and the US/EU/NATO, which are essentially doing the same thing here, is questionable]

Changing worldviews is one of the most challenging things we humans do.

What makes 24 February 2022 such a shocking date in recent history is that there was no longer any attempt to hide the use of force. It was an outright invasion of a neighbouring country, the likes of which we have not seen in Europe since Nazi Germany did the same in the 1930s. As it was not a very successful invasion either, a bloody trench war has been raging for years, alongside gross abuses against the Ukrainian civilian population.

[this is confusing, at best, for Mikkelsen appears to be saying that the Ukrainian/Azov shelling of the Donbass since 2014 would, in effect, be Russia’s fault]

For the rest of Europe, the post-World War II settlement marked a final break with that kind of politics. There is a clear before and after, and all European politics since then has been fundamentally about resolving conflicts in a way other than by taking up arms. That doesn’t mean that conflicts or disagreements were gone, they just weren’t resolved with tanks on European soil.

[soft humanitarians that we are, we merely used air force-delivered bombs against Yugoslavia in 1999, which Chris Clark (Regius Prof., Cambridge U) wrote about the ‘Kosovo War’ in his 2012 best-selling book The Sleepwalkers (from the UK ed., Allen Lane, pp. 456-57; my emphases): ‘It would certainly be misleading to think of the Austrian note [the ultimatum to Serbia delivered on 28 July 1914] as an anomalous regression into a barbaric and bygone era before the rise of sovereign states. The Austrian note was a great deal milder, for example, than the ultimatum presented by NATO to Serbia-Yugoslavia in the form of the Rambouillet Agreement drawn up in February and March 1999 to force the Serbs into complying with NATO policy in Kosovo.’ Please find out ‘more’ about this here]

I think that’s why it was so difficult for politicians and public opinion to imagine that this could happen. Changing your world view is one of the most difficult things we humans do. Even in Kyiv, they didn't believe the American message that a major war was imminent. But they know that now, and they have also managed to defend themselves after the initial shock was shaken off.

[could it have something to do with gaslighting by dishonest politicians and their willing collaborators in legacy media, such as NRK, Mr. Mikkelsen?]

Western politicians also reacted quickly, many of them surprisingly quickly given history.

Until last year, the world allowed Russia to intervene and bully its neighbours.

I thought about this as I walked past the illuminated monument in Berlin to the Soviet effort to win the Second World War, also last autumn. It was strange to see a Soviet tank on a pedestal in the dark of night in the German capital, with Ukraine just a long car ride away.

It stands there as a monument to liberation, but I wonder what the Germans are really thinking in the light of what is happening now.

[read my Substack, Sigurd, would you?]

Chancellor Olaf Scholz gave a remarkable speech to the Bundestag just three days after the invasion, in which he announced unequivocal support for Ukraine and the rearmament of its army.

Yes, it has been slow, but Germany’s underlying guiding principle was to seek friendship and alliance with Russia after two devastating world wars. As a result, Germany has had to change more fundamentally than any other European country.

Further west, France also had to shed its slightly romantic notions of great power negotiations with Russia. Here at home [in Norway], we changed a half-century-long practice of not sending arms to a country at war without major political disagreements.

It is easy to see in retrospect that Russia’s relationship with borders is a delicate one.

The EU and the US also quickly agreed on a large package of sanctions. That was not a foregone conclusion either. [No? What about the RAND report…] There are different countries with different interests here, and this unity and ability to act and adjust policy after the invasion shows that democracies can also react quickly when needed.

We will need that going forward. Because there are no obvious solutions to the war in Ukraine, nor is it the case that the whole world shares the West’s view on the Ukraine war.

Russia has been active in Africa to rally support there. Latin America and the Middle East tend to see this through anti-American lenses because of their own experiences with American power play. China, for its part, is looking for a role as an ally of Russia without wanting to fully side with Russia, at least so far.

Bottom Lines

I’ve highlighted the most egregious fabrications in both pieces, and I do think, on balance, esp. the second piece is more forthright than anything else I’ve seen in legacy media so far.

Mikkelsen tacitly admits to a number of issues—grievances—that have so far been anathema to mainstream media, incl. the rather lopsided-ness of ‘the West’s view on the Ukraine war’. Sure, most readers of these pages know about this, but Western state broadcasters in particular have been loath to even implicitly mention this.

The lies and fabrications about WW2 analogies are also par for the course, but I just don’t see how these will not, eventually, lead to a re-consideration of WW2.

Compared to German-speaking politics and media, Norwegians are getting a much more nuanced and reflective message; sure, that bar is extremely low, but it’s at least worthwhile to note that at least Stoltenberg, deranged and delusional as he may be, isn’t suffering from the same kind of abject and utter madness as, say, the German Greens. A consolation prize, at best, but not nothing.

I do see a great deal of escalation potential for NATO ‘expanding’ its ‘security ideas’ further to East Asia.

Then again, we’ll probably be told that Oceania has always been at war with East Asia. And the memory-holing and gaslighting will be replayed.

Let’s not get fooled again.

This was probably an attempt at subtlety in revisionism by him:

"It was strange to see a Soviet tank on a pedestal in the dark of night in the German capital, with Ukraine just a long car ride away.

It stands there as a monument to liberation..."

Liberation was not was the soviet did in Germany. Invasion and occupation are the correct terms.

On the other hand, Norway has long had the nickname "the last Soviet State" here in Sweden due to Norway being even more corporatist than us (making us able to ignore our own faults of the same nature).

And as a professional writer, surely Mikkelsen would know that being openly partisan, even proclaiming it and using the explanation of why is a much better tool for garnering respect even from opponents as well as convincing people of the rightness of the cause, than trying to "put make-up on a sow" like he is doing?

At times you feel almost sorry for the authors of such articles - not only do they have to learn facts, but then have to re-construct them to fit a certain narrative demanded by the boss. One has to have no issues lying and twisting facts to earn a living. Not the job for everyone.