NATO's 'War', Geopolitics, and the Folly of EUrocrats

Why Kennedy's Rise & Fall of the Great Powers matters much more than the poli-sci BS emanating from the 'West' ever since: NATO is brain-dead, and here's a primer into the likely consequences

In October 2019, French president and paid globalist shill Emmanuel Macron made a few waves by declaring NATO ‘brain-dead’, which is about as much as anyone should remember about the present situation. As quoted by The Economist (paywalled),

Europe stands on ‘the edge of a precipice’, he says, and needs to start thinking of itself strategically as a geopolitical power; otherwise we will ‘no longer be in control of our destiny’.

That interview—and in particular this blunt admission (a gaffe?)—is very telling on two accounts: first, the neuro-degenerative consequences of all matters Covid-19 have quite effectively memory-holed Mr. Macron’s opinion, as evidenced by the massive upsurge in media reports suggesting NATO’s increasing popularity among wide cross-sections of the EUropean population.

This is insane on the face of it, but even more so it shows both the decay of historical consciousness across the board and the degeneracy of the EUrocratura in particular. Here, I shall restrict myself to mentioning NATO’s aggression against Yugoslavia in 1999 and the subsequent misadventures in central and western Asia (Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria) as well as in Africa (Libya) to make the point that all the hyperventilating BS coming from our betters is just that: huffing and puffing, but ultimately it is inconsequential.

Geopolitics 101

What matters in geopolitics are the following three facts, and you’re herewith warmly invited to disagree with any or all of them:

Military capabilities matter most, and in this regard no EUropean country is more than a dwarf. Yes, high-tech weapons are all nice, but basically no NATO country has much to offer in terms of mechanised armour; there’s a lot of fighter jets and close air support (helicopters), but NATO membership essentially makes governments invest heavily in high-tech gimmicks and ‘smart’ devices for light infantry. It’s immensely costly, which is to say that it’s a boon for the highly integrated and class-conscious armaments manufacturers, but it’s hardly a winning argument in a war. Remember in this context that the general public is highly averse to any combat engagement anywhere and balks at even the prospect of potential casualties (hence the preponderance of UN peacekeepers from the Global South in real hotspots, such as Eastern Congo).

Economic power, of course, underwrites military capabilities, and there’s a lot to say about this (for starters, see Michael Hudson’s recent piece), and here, too, ‘Western’ planners must, in effect, face the uncomfortable truths of a mainly goods-and-service-oriented economy with limited manufacturing capabilities (which also cannot be scaled up rapidly to meet, say, increased military demand, in part due to EU/EEC trade and competition policies). In addition, esp. Germany and a few of its exporting neighbours are not only highly integrated economically with each other (which, by the way, further betray the ultimately inconsequential legal niceties of ‘neutrality’ claimed by both Austria and Switzerland), but their economic model—export high-value goods, such as BMWs or other expensive stuff ‘made in the EU’—is heavily dependent on customers. Many of whom are high net-worth individuals in China and Russia, hence the ludicrous follies in terms of the entirely expectable economic fall-out (to say nothing about EUrope’s energy security).

Credibility, or what Joseph Nye (in-) famously called ‘soft power’, is the third main ingredient, which is heavily contingent on both military and economic power-political potentials. Yet, I’d argue that being taken seriously also matters in both war and peace, as well as everywhere in-between. Take, say, the illegal US invasion of Iraq in 2003—and, by the way, if you don’t like that description, you may resort to the term ‘special operation’—which may be considered as an international engagement that everyone who’s watched The Godfather is able to understand. ‘Walk softly, and carry a big stick’, in Teddy Roosevelt’s famous dictum, is what matters, and being in a superior position typically conveys the considerable advantage of not having to resort to economic and/or military coercion. The fact that the collective ‘West’ has taken that particular road vis-à-vis Russia tells you everything you need to know about international relations: it’s not only that Russia is simply ‘too important and big’ to be pushed around, but the refusal of the US-led bloc to actually do anything meaningful beyond huffing and puffing shows the ‘West’s’ essential weakness.

Sidenote: there’s nothing the ‘West’ will—or can—can actually do about the Russian operations against Ukraine (that is, short of nuclear war), and while the entire Maidan-instigated misadventure was an outright folly, one shall also remember that whatever in terms of military hardware the ‘West’ is trying to funnel into Ukraine now will only prolong the agony of the people suffering in this conflict. It’s a shame that all the ‘Western’ leaders are like that, as in, totally irresponsible and careless with respect to the lives of others.

As regards the larger points made above, I shall conclude this post with a brief reminder from none other than Paul Kennedy’s memorable and very much readable The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (1989), p. xv (emphasis in the original):

The triumph of any one Great Power…or the collapse of another, has usually been the consequence of lengthy fighting by its armed forces; but it has also been the consequence of more or less efficient utilization of the state’s productive economic resources in wartime, and, further in the background, of the way in which that state’s economy had been rising or falling, relative to the other leading nations, in the decades preceding the actual conflict. For that reason, how a Great Power’s position steadily alters in peacetime is as important to this study as how it fights in wartime.

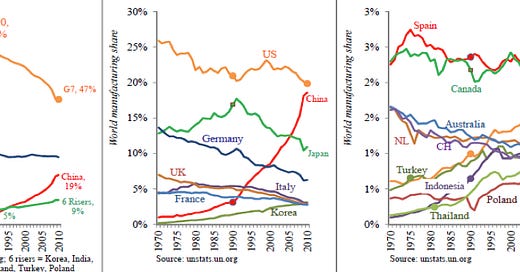

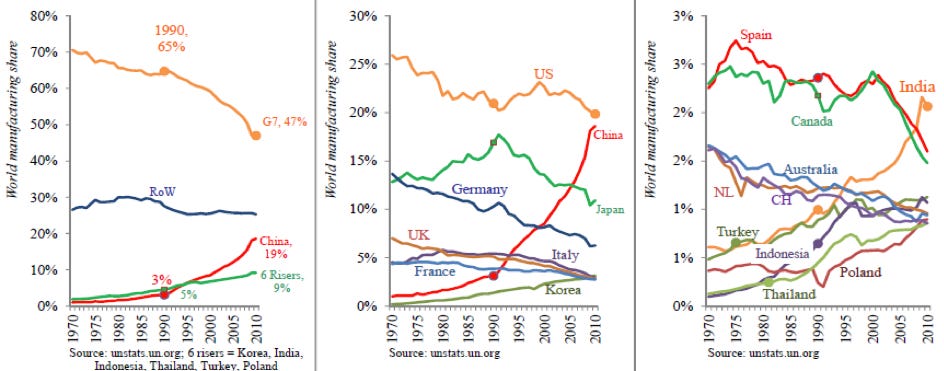

And on that particular matter, I refer you to a selection of manufacturing capabilities since the 1970s—do you notice something?

And these graphs are telling you the same as the below two pictures, which show Shanghai in 1990 and 2010, respectively (for orientation, I’ve added a blue arrow to show the one large building that didn’t change):

And 2010:

So, today’s question for you may thus be summarised as follows:

How do you think the present situation will play out in the next couple of years?

The easy way to comment on this topic is, Huntington was right. Problem with that is, he's no longer very widely recognised in political science, having been labeled reactionary, old-fashioned (as if that makes one wrong somehow), and not in time with the changing times.

As for EU-rope, that smart thing to do for the Union and the member-nations, would have been to use the opportunity provided by the crumbling USSR in the 1991-2000 period to leave NATO and tell the USA to remove their troops, weapons and bases.

And then, from there create an EU defense pact and command structure, split three ways:

Northern, South-Eastern and Western fronts, all built up to be mutually supportive in case of hypothetical invasion by "Africa", the Middle East, Russia, and the USA (with a contingency for the near-certain backstab from Perfidious Albion in case of conflict between Europe and USA).

Obviously letting the respectie militaries handle the build-up and co-operation of forces, command structure and so on, keeping in mind what happens when politicians try to play at being soldiers (well-known 1941 French debacle and the failure of Scandinavia to re-arm during the 1920s being the most triumphant examples I can think of right now).

But since no EU-nation trust the others nor the Union itself, not when push comes to shove, that plan (which did exist, at least as an idea) came to nothing - the USA barely needed to do any lobbying to herd Blair and the UK into its fold, and once that was done, they could run rough-shod over the EU, especially in light of how it completely fumbled the Balkans' war.

Now, we must fall and crumble a bit further, before we can sober up and get real about real things.