Germany 1918: Gunpowder, Treason and Plot by the Business, Financial, and Military Elites against the German People

Part 1 (of 2) of an in-depth investigation into the shenanigans that led to many of the developments of the 20th and 21st centuries, including the re-emergence of Neo-Nazis seemingly everywhere

Preliminary notes: we talk so much about the seemingly ever-quickening pace of current events, and we’re not nearly doing enough to further our understanding of how we arrived in our time. One of the biggest problems of my field, History, is actually the (too-) close proximity of most colleagues—the overwhelming majority of my colleagues ‘does’ contemporary history, i.e., the period after WWI—to the events and developments they are trying to understand.

This kind of ‘presentism’ typically induces quite a number of epistemological biases, but there is also another aspect to consider, which is often outright ignored and (or) belittled: the closer one is to whatever current or recent event, the more important said moment appears ‘in the grander scheme of things’. Often reinforced by presumed feelings of equanimity to reasonable distance (doubt), these dual biases—perhaps of a dialectical nature—are thus subject to at least three major forcings that, while interrelated, are rendering any given event or development quite ‘decorated’ with ignorance, lop-sided considerations, and individual presumptions of moral clarity, ideological blinders, and (or) the absence of relevant, if not necessary, context omitted in the heat of the moment.

Today, I’d like to share a few thoughts with you about one of the seminal moments of the more recent past: the end of World War I in Germany, what the confusion in Berlin and across the country meant to contemporaries, and what its most important long-term consequences were.

One last short paragraph filled with caveats: a long time ago, I resolved that, professionally speaking, I won’t touch contemporary history as my main field of research. The pitfalls of trying to avoid ‘the conventional wisdom’—one may study the period from around 1900 to the present, alright, but the outcome of one’s research is, of course, predetermined by politico-ideological concerns for one’s career, private fortunes, and family—led me to spend my research and teaching efforts on the late medieval and early modern period, which in my case means Central and Eastern Europe from around 1350 to 1850. I greatly love learning about these past times and their inhabitants, but this essay, conceived as it is as a three-part endeavour, will be something I’m personally interested in (as anyone who’s interested in the history of the present circumstances should be), but my engagement with it must not necessarily be too scholarly. I also elected to keep annotations and the like to the bare minimum.

Introduction

So, what is the following going to be about? We hear so much about historical reasons and the like every day, and certainly there’s many other periods that elicit comparable importance by posterity. Yet, the end of the Great War (1914-18) in Germany was a quite spectacular series of event: the following is about war and peace, universal suffrage (achieved in Germany before in the UK and the US, by the way), and the institution of a democratic republic in Central Europe.

While momentous, these developments are overly exaggerated by the powers-that-be, which was quite visibly put on display in autumn 2018 on the occasion of the commemorative events of their centenary. The revolution’s real, or true, aims—direct, instead of representative, democracy, the control of parliament by peoples’ councils elected directly from among the citizenry, and the break-up of the Prusso-German agglomeration of power-sharing between big government, big business, and high finance—are conveniently ignored, lest they somehow muddy the waters of the self-congratulatory festivities of the high, rich, and mighty. Similarly downplayed, if not outright ignored, were (are) the perpetrators of oppressive violence directed against the citizenry, in particular the Freikorps (paramilitary formations led by demobilised officers who feared a Bolshevik Revolution), the remnants of the once-proud army, rechristened as Reichswehr (i.e., professional soldiers who shot at their fellow-citizens), and the emergent extremist, or proto-fascistic, formations.

All three of them colluded in the violent and bloody suppression of the demands most forcefully espoused by the workers’ and citizens’ councils. More often than not, these events and the key players in this war by state and non-, or para-, state actors against the German people is ignored or belittled. I certainly hope that these essays here will serve as a memorial to the sacrifice of a people whose historical memory has been quite distorted and, frankly, abused.

I do not advance any particular agenda here, but I shall hope that by reading the below lines, you, my dear reader, will end up more informed about these crucial days in autumn 1918 than you were before. And the more informed the citizenry, the better citizens they make.

In this first part, we shall discuss the legacies of three key moments in German history that are quintessential for any understanding of the past 150 years in general, in particular of the 1918 revolution: first, the foundation of the (second) German Empire in early 1871; the Great War (which we now call the First World War), and 3 October 1918 when, for the first time, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) entered government. (The SPD had been the single-largest parliamentary faction before 1914, but the ‘bourgeois’, or bürgerliche, bloc, in cahoots with the more reactionary forces, kept the political representatives of the working class—before 1917 the largest and best-organised left-wing party on the planet—away from the levers of power.) This third moment is crucial for the correct understanding of many of the travails and ills that befell first Germany and later most of Europe, if not the world, for the political participation of the SPD allowed those responsible for the disastrous decision to go to war, as well as its subsequent conduct, to largely escape scrutiny. In other words, the events of October 1918 are inextricably linked to the notion, later used to such great political effect by Adolf Hitler, of the undefeated German army that had been ‘stabbed in the back’ by craven politicians branded as ‘November criminals’.

In German discourse, the term ‘revolution’ is rather negatively connotated, irrespective of its meaning: deriving from Latin revolutio, a sudden turn-around, the process of revolution signifies a ‘return to a prior, more desirable situation’ rather than, say, the first tentative steps towards a glorious new future. Note that these peculiarities of both the German language and discourse are, well, germane to this particular area of Central Europe. Yes, we German-speakers consider the French Revolution (of 1789, any other such event must be qualified), the Russian Revolutions of 1905 and 1917 (both in February and October and November), and the Chinese Revolution of 1949, as well as the Cuban and Iranian Revolutions of 1959 and 1979, respectively. As this incomplete listing shows, if German-speakers refer to revolutions, they need to be properly identified (but a revolution itself is by definition neither a ‘right-wing’ or ‘left-wing’ occurrence). As far as German history is concerned, perhaps the closest comparable event might be the Revolution of 1848.

The German November Revolution of 1918 and the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic (6 April-3 May 1919) are conventionally discussed, if at-all, as Bolshevik-inspired orgy of violence.

Yet, these upheavals arguably constituted not only a ‘real’ revolution in terms of sudden political, social, and economic change. Contrary to the Revolutions of especially 1848, the events of November 1918 were grounded in mass-support (not that the bourgeois liberals of 1848 didn’t have support, but theirs was arguably much, much smaller), which is to say that the November Revolution was as close to the ideals of a democratic and peaceful régime change. It was also almost devoid of bloodshed and violence, which came later—with the counter-revolution led by the state and carried out by non- and para-state actors.

Fact and Fiction about November 1918

The November Revolution was also a creative, or constituent, moment that had a lasting influence. This event was anticipated by mass strikes of industrial workers in favour of peace. It were the poor, destitute, and increasingly hungry masses that were the foundation of the above-mentioned changes in government that precipitated the end of the war and made peace possible. Both monarchy and the remaining vestiges of the (semi-) feudal socio-economic order were ended in November 1918: at no point thereafter, in particular after WWII, would (constitutional) monarchy re-appear as a viable concept. Unlike in, say, post-fascist Italy (which held such a referendum in 1946), no such thought was entertained in Germany.

What was achieved in November 1918? First of all, suffrage was made universal, which is to say that the workers’ and soldiers’ councils set up in November were elected by both men and women (which is something, incidentally, the ‘Communist Manifesto’ did not envision). Thus, the German Revolution was instrumental in showing the viability—and practicability—of a kind of direct democracy on the basis of workers’ (and soldiers’) councils, which sets reality apart from any allegation of ‘Bolshevism’ or dictatorship. It is, indeed, as far from the truth as possible to allege that violent left-wing extremism was at the heart of the November Revolution.

To briefly illustrate this misleading claim, here’s what Dr. Mark Jones, Professor of History at University College Dublin, Ireland (profile here), wrote about that particular aspect in his first book, Founding Weimar, which was published by Cambridge University Press in 2016:

Violence is a physical action: it causes injury and death and it reminds all who encounter it of the fragility of their own physical existence. Therefore, this study sets out to understand how the threat posed by the corporeality of violence interacted with political cultures in the revolutionary winter of 1918-19… these acts of real physical violence helped to shape a canvass of imaginaries of future violence on a worse scale… As a result of their interaction with real acts of violence, this book argues that these fears meant that the leaders of the new state turned to foundation violence as a means of calming a nervous audience and demonstrating their indisputable right to rule. (p. 2; references omitted; my emphases)

And here’s the same Mr. Jones (MJ; Q: Arno Widmann) in an interview conducted by the Frankfurter Rundschau (12 Nov. 2018) on the occasion of the centenary of the end of WWI:

Q: The [new German] republic did not so much defend itself against the old power structures. Rather, it used [the old power structures] to put down more radical left forces.

MJ: There were not only fears and fantasies. There was also an actual left danger. Supporters of the [Communist-led] Spartacus League were also out there with machine guns. The republic confronted its leftist enemies with violence. The Social Democrats wanted to make it clear that they stood for law and order, and that they would not allow a civil war. A new régime, a new state often justifies itself through the violence it exercises…

Q: The republic was built on violence.

MJ: We find that hard to accept, though, and also we prefer to obscure this fact because we believe that democracy is good, and violence is bad. Perhaps there would have been other ways of acting against the left-wing opponents of the republic at that time. Yet politically that would not have been accepted. These were uncertain times, and the state had to show that it could offer its citizens security. It was about defeating the enemy. Mentally, people had not yet been demobilised. The immediate danger to the republic in 1918-19 did not originate from the right, but from the left. That is why the republic had to defend itself against the Spartacists by means of the old [i.e., the Empire’s] military. (translation and emphases mine)

These brief text passages are, of course, indicative of the revisionist trajectory of recent discourse on the November Revolution. Still, it is worth pointing out that this kind of—and let’s not mince words here—fake history has quite deep roots in the post-1945 German public sphere. Way back in 1963, Peter von Oertzen, SPD Minister of Culture and Education of Lower Saxony, held that

it seems…not coincidental that the conventional accounts of the November Revolution have mostly portrayed the [workers’ and soldiers’] councils not only in a very misleading way, but virtually excluded them at-all. (Betriebsräte in der Novemberrevolution, repr. Bonn-Bad Godesberg, 1976, p. 53)

Conventionally, most accounts of the (later) Weimar Republic acknowledge the existence and role of works councils (Betriebsräte), which are, of course, not the same as the workers’ councils of November 1918. This very much relevant distinction is further borne out by the Weimar Constitution whose Art. 165 merely obliges these works councils to cooperate with management (and ownership) to the benefit of the workers and the firm.—Yet, even this rather vague formulation clearly shows the difference between works vs. workers’ councils: the latter were directly-elected representatives of the working people (classes), and there set-up did not include any obligation whatsoever to cooperate with ‘the firms’, i.e., Germany’s business class.

Why, then, aren’t we talking more about November 1918?

Even the most cursory glance at the above reveals that the answer is—betrayal, if not outright treason. Those who were in power in November 1918 betrayed the Revolution by collaborating with the ‘means of the old military’. The most immediate consequence thereof is the acknowledgement of the direct continuities between those who in 1918-19 betrayed the German people—and those who regained (domestic) political power in West Germany in 1949. Therefore, most historical accounts of the November Revolution continue to be ‘informed’ by the legacies of these acts of treason.

Take, say, the example of the SPD Philipp Scheidemann Stiftung (foundation), named in ‘honour’ of one of the leading social democratic politicians of the events of November 1918. It was Mr. Scheidemann who, on 9 November 1918, proclaimed the republic in Berlin. Before his move to the capital, he was mayor of Kassel (where there is a Philipp Scheidemann Haus), and in autumn 1918, nearby Schloss Wilhelmshöhe served as the HQ of ‘the old military’.

One does not need to look much further to identify the rank hypocrisy, which stinks to high heaven in my opinion, once one considers that Mr. Scheidemann and his ilk of the SPD were in continuous close contact with the German Army during these heady days of 1918-19; similarly hypocritical is the fact that another SPD-led foundation, named after Friedrich Ebert (who became the first president of the Weimar Republic in 1919), continues to play an important role in domestic German politics to this day. Needless to say, there is no-one in the SPD who wishes to engage with this particularly sordid history.

Speaking of 9 November in Germany, there is not but 1918 that is important, but there is also Kristallnacht, 9-10 November 1938. The latter, known in English as ‘Night of Broken Glass’ or ‘November Pogrom’, marks the advent of the massive state-orchestrated Anti-Semitic campaign of Nazi Germany. Quite frequently, both dates—1918 and 1938—are conflated by the media, as happened in the major German daily Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on 9 November 2018 when Reinhard Müller wrote (paywalled):

Was this not the day in 1938 when an organised mob hunted down Jews and set fire to synagogues…? And on that day in 1918, weren’t many shocked to hear of the downfall of the Kaiser and the proclamation of the Republic?

It is indeed stranger than fiction to conflate these two very different dates, their meanings, and contexts: one (9 Nov. 1918) marked the advent of the first parliamentary republic, while the other (9 Nov. 1938) is a day that lives on in infamy, marred by National Socialist dictatorship, Anti-Semitism, and state-sanctioned mob violence. So, let’s not mince words about the Night of Broken Glass either: this was a consciously orchestrated ‘event’, it did not just ‘happen by chance’, and it wasn’t a ‘spontaneous riot’. Those looters and thugs came from the ranks of the Nazi régime’s paramilitary formations, in particular the Schutzstaffel (SS) and Sturmabteilung (SA). The action was carefully planned and staged by the Nazi leadership and carried out by the régime’s henchmen, the true heirs of the Freikorps who killed many German workers and citizens in the aftermath of November 1918.

Many a Nazi leader were members of the Freikorps murderers, and one of their formations proudly carried the Swastika on their steel helmets after January 1920. Hence, by staging the November Pogrom on the very same 9 November, the Nazi leadership sought to erase, or at ‘overcome’ any positive connotation that date might have conveyed, in particular with regard to left-wing politics. The end of WWI—and Germany’s defeat—was all ‘the Jews’ fault’, was incorporated into Nazi propaganda whose long-term success may be observed by the conflation of both 1918 and 1938 discussed above. Both dates may only be related to in combination because of Dr. Goebbels’ smear campaign, and they should not be treated together.

History matters, in particular that of November 1918

There are three major trajectories that are of crucial importance for a comprehensive understanding of the November Revolution: first, the foundation of the (second) German Empire in early 1871; second, the Great War, which was welcomed by the German business and military elites; and, third, the moment when the Social Democratic Party (SPD) entered government on 3 October 1918, which resulted in the formal incorporation of the leading opposition party into the ruling elites. three events considerably impacted the SPD and the subsequent development of social democracy in Germany, and we shall explore them below.

As is quite well-known and acknowledged by scholarship, the bourgeois Revolution of 1848 failed to produce a German national state. All attempts to create a unified and post-feudal Germany came to naught, and this was in no small part of the ‘Spectre of Communism’, the mainly perceived, if rising, power of the working classes. Consequently, the German middle classes entered into a (Faustian) bargain with the proponents of the Old Regime, namely the various crowned heads and the large aristocratic landowners, the Junker. For time being, the many small and medium-sized states remained, but in 1866, the Prussian-led North-German Confederation—a kind of trade-based customs and economic union, inaugurated the seemingly inexorable march towards a political union. Incidentally, this Confederation shows many similarities with the EU and the position Germany occupies within it (a point that’s not lost on Ramin Mazaheri who similarly, albeit from a very different point of view, located these origins in 1871). Still, the main take-away is that economic arrangements alone won’t forge a coherent political entity, as the example of the wars between Prussia against Austria (1866) and France (1870-71) show.

In parallel to Bismarck’s ‘unity through Prussia’ policy—better known by the infamous slogan ‘blood and iron’—however, the third quarter of the 19th century gave rise to modern industrial capitalism, as magisterially explained by Eric Hobsbawm in his Age of Capital (repr., London, 1996). Soon, the new spirit of the age found itself too constrained by the many German states.

German Unity by Blood and Iron

On 19 July 1870, Bismarck’s policies bore fruit in the guise of a French declaration of war against Prussia. Certainly, Napoleon III and the French elites expected to widen the economic base of their own capitalist economy, much like the German business class aimed for the same outcome, albeit in their favour. Within a few months, the Prussian army soundly defeated their opponents, cheered on by their South German camp followers. German unity was manufactured by war in 1870-71. Thus, the initially democratic aim of a constitutional monarchy was inverted on three counts:

On 18 January 1871, the German Empire was proclaimed in Versailles, which served both as a humiliation of, and long-lasting provocation for, France.

The new Empire annexed Alsace-Lorraine, which gave Germany a firm foothold on the left bank of the Rhine, but at the same time it fuelled French resentment for generations until—the Versailles Treaty of 1919.

Yet, these dealings also included a kind of arrangement with the French business class whose (temporary) acquiescence was bought by Franco-Prussian (German) collusion against the Paris Commune. Prussian soldiers contributed to the slaughter of thousands of Parisians and received reparations from the new French Third Republic, as explained by none other than Bismarck:

As regards military developments, we may hope that the struggle outside and in Paris is coming to a close. As soon as the troops of the [French] government are victorious—which we will now facilitate…by speeding up the release of prisoners—a first instalment of five hundred million francs will have to take place within thirty days. (Sebastian Haffner, ‘Die Pariser Kommune’ in Zwecklegenden: Die SPD und das Scheitern der Arbeiterbewegung, eds. Sebastian Haffner, Stephan Hermlin, and Kurt Tucholsky, Berlin, 1996, p. 45.)

There was a German national state, and it is necessary to understand that it came into existence through war, by way of premeditated and organised violence against the working class, and fuelled the ‘hereditary enmity’ of (against) France. Consequently, the new imperial constitution contained only a few civil liberties: limited suffrage (three classes, based on property qualifications); a very weak parliament, the Reichstag, and a government that was not responsible to it; and the persistence of autocratic monarchy supported by the large landowners, in particular visible on the state level. The ensuing massive economic expansion was in no small part financed by French reparations, which directly fed into comparable demands in 1918-19.

It was against this background that German Social Democracy emerged. Despite an official ban (1878-90) and the weighted suffrage, the SPD quickly rose to prominence and eventually became the single-largest political party in the Reichstag. By 1914, the SPD counted approx. 1m members who garnered another 3.5m votes. During these decades of economic and political growth, outside influences similarly emerged, which contributed to the slow drift of the party towards integration into the bourgeois-capitalist politico-economic system and society. Within the SPD, these contradictory positions remained unaddressed before 1914, but at least a clear rejection of ‘imperialist warfare’ was retained.

The Great War

The First World War plays an equally important, if typically misleadingly characterised, role in all of this. Culturally as well as in public discourse, the horrors of (especially the West Front) are what is ‘the West’ remembers: the nightmares of Verdun and the Somme (1916) the slaughterhouse of Flanders Fields (1915, 1917), and the German almost-victory in spring and summer 1918 are major tropes of both discourse and remembrance. Among the transatlantic ‘Western’ allies, the memory of the war culminates on (in) Armistice Day, 11 November, which concluded what US strategic planner George F. Kennan (in-) famously characterised as ‘the seminar catastrophe of the 20th century’.

Like virtually everything else in history, there are, of course, kernels of truth to this kind of (fake) history, whose more egregious webs of lies begin with the origins: the war was a premeditated attack planned with cunning, according to Fritz Fischer’s Germany’s Aims in the First World War (orig. Düsseldorf, 1967, trans. 1967), which, not unlike today’s legacy media, ties this conflict to the Second World War and all the atrocities committed by Nazi Germany. The groundwork for most of these ‘connections’ was laid from 1914 onwards by ‘Western’ propaganda, mainly emanating from Britain and the US, as explained a decade later by the main architect of ‘modern’ public relations, Edward Bernays, in his Propaganda (New York, 1928).

Despite the many geographical and thematic biases, there is but one major change in the hagiography of the First World War: Christopher Clark’s The Sleepwalkers (London, 2012), which played a crucial role in ‘helping’ especially Germany in reducing, if not completely losing, its century-old shame. According to Mr. Clark, Regius (by royal appointment, profile here) Professor of History at Cambridge University, the ‘true’ origins of the war lie elsewhere, namely in London, Paris, St. Petersburg, Rome, and—Belgrade.

Sidenote: I will not dive into the narrative presented by Clark here, but I will say the following about the book: I first read it a decade ago, and while I appreciate the nuances and details offered, the main problem is the underlying hypothesis. By arbitrarily reaching back to a bloody coup d’état in Serbia at the beginning of the 20th century (but leaving out Serbia’s history of the preceding century, i.e., the relevant background, which shows that this unhappy, medium-sized people had been torn between pro-Vienna [‘West’] vs. pro-St. Petersburg [‘Russia’] leanings, including a number of earlier major policy changes), the story told by Clark appears more than a simplistic morality play rather than a serious enquiry in the subject matter.

All told, it’s a very readable book, but it, too, comes with considerable blind spots, a seemingly arbitrary opening, and a quite political message: by virtue of his book, Clark has done more to ‘absolve’ the Germans of their ‘quasi-original sin’ than most other people. I won’t expand on this here, but I feel the need to stress that one does not ‘sleepwalk’ into something as dreaded and envisioned as the major industrial slaughter that became known as WWI. While this topic itself may be dealt with at length at another time, it must be mentioned that war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia was declared in the name of emperor Francis Joseph who retained, to the very end, the prerogative to determine the course of foreign affairs of the dual monarchy.

There was nothing ‘special’, or particularly ‘German’, about the origins of the First World War. Much like the United States and Japan, the German Empire was founded on ‘blood and iron’ in the 1860s and 1870s, it was a firmly capitalist state dominated by big business, high finance, and a political elite utterly devoid of morality. These base qualities of the bourgeois world-economy and its other main exponents—Britain, France, and Russia, Austria-Hungary and Italy, as well as the middling and smaller European powers—expansion by any means necessary was the driving force. If possible, the main centres of economic and military power collaborated to loot and pillage the earth, as happened, e.g., in Berlin 1878.

Still, Germany (and Japan as well as the US) arrived quite late to colonial ventures and never really managed to derive returns on investment as colossal as the British and French elites. Hence, over the late 19th century, it became fashionable among German politicians to demand ‘a place in the sun’, an expansionist-militarist political platform that bridged the ideological divide and found a number of vehement proponents also among the more ‘centrist’ factions of the SPD. Among the latter, Gustav Noske (remember that name), member of parliament from 1906 onwards, was its chief and quite vocal supporter.

Given Germany’s exposed strategic position in-between France and Russia, the general staff devised a number of war plans to deal with any contingency. While this is neither the time nor the place to review these in detail, it suffices to say that these plans culminated in the so-called Schlieffen Plan, which envisioned a rapid advance (victory) against France before facing Russia in the east. The plan hinged on notion that the former was easier to defeat (smaller size, more efficient organization) than the large Russian Empire and its (presumed) longer mobilisation time.

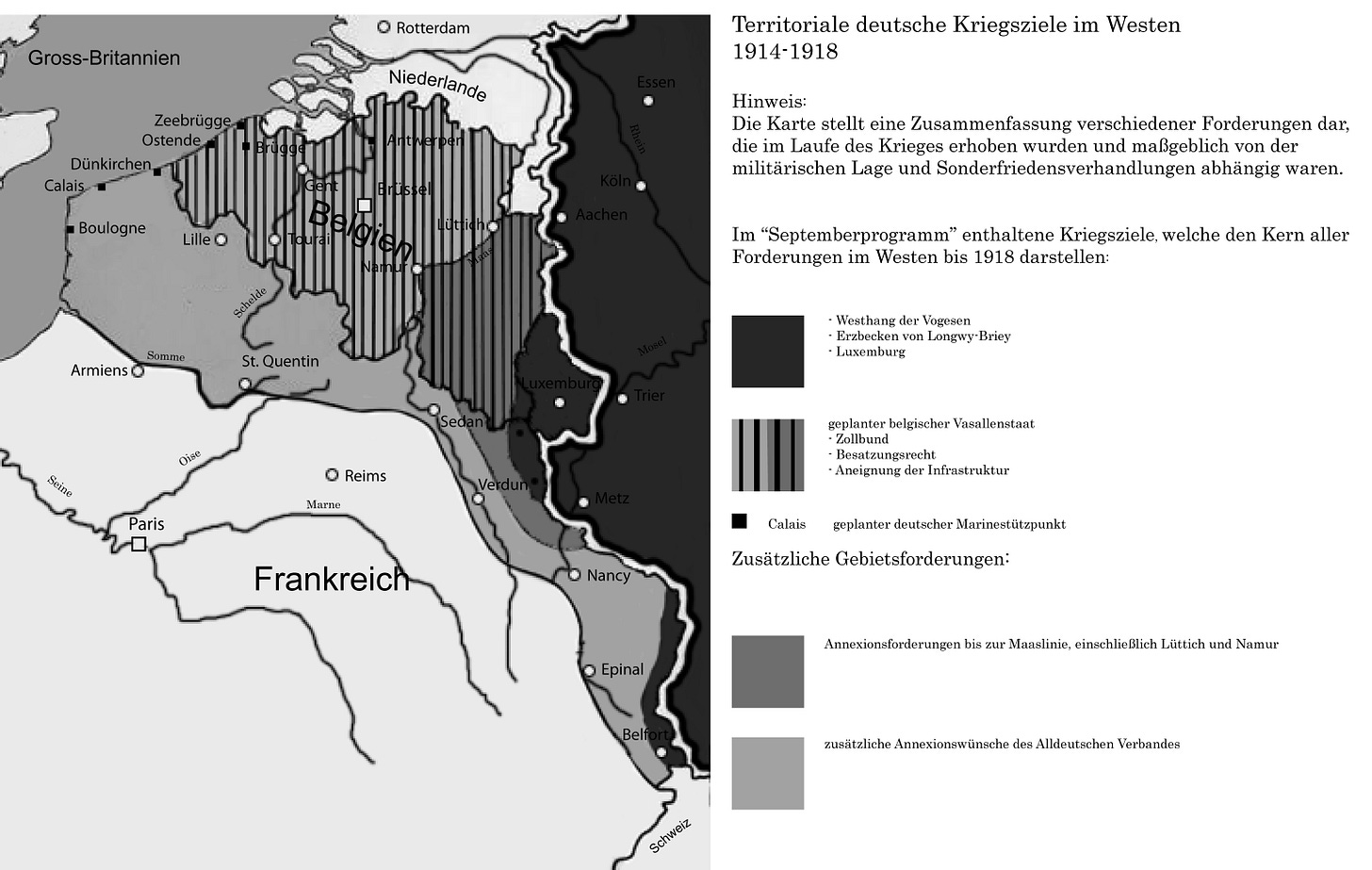

Drafted in 1905 and subsequently modified, the military planners tried to provide policymakers with a way out of the geostrategic dilemma faced by Germany. Of course, a German victory would have ushered in an era of dominance of Europe by a single powerful state (Germany), which increased the heartrates of the leading German industrialists. Once the war got going, there were numerous additions and wishes deposited on the doorstep of the German government that all related to the possible gains after military victory.

Take, say, what Fritz Thyssen, owner of the second-largest German steel conglomerate, had to say about ‘the future of Europe’:

Our army is outright [sic] magnificent…I can see how big and bold everything was planned in Berlin…The time is approaching when we…must prepare the peace treaty…If [once] we conclude the war as gloriously as we have begun it, we shall crush France and Russia and dictate terms…to both…

As far as western [Europe] is concerned, first of all, I am of the opinion that [the following] must be annexed to the Empire: Belgium, the [French] Departements du Nord and Pas de Calais with the ports of Dunkirk and Boulogne, the Departement of Meurthe and Moselle with the French border fortresses, with the Meuse as border up to Givet, as well as in the south the Departements of Vosges and Haut-Saone with the fortified city of Belfort.

Russia must cede to us the Baltic provinces, perhaps parts of Poland and [the] Don region with Odessa and the Crimea, as well as Azov territories and the Caucasus, which would allow us to reach Asia Minor and Persia by land…We will only be able to achieve a position of world power, if we control the Caucasus and Asia Minor to be able to reach England in Egypt and India…(quoted in Europastrategien des deutschen Kapitals 1900-1945, ed. Reinhard Opitz, Bonn 1994, p. 222; my translation and emphases)

Both maps via Wikipedia (German and French versions only, used here for illustrative purposes only):

The Great War began with the Austro-Hungarian declaration of war against Serbia (28 July 1914), with hostilities beginning with the bombardment of Belgrade the next day. On 2 August, German troops took over neighbouring Luxembourg, followed by the advance into Belgium two days later. The war itself was conducted with brutality, war crimes, and the like on all sides; everyone employed the means of industrialised warfare to the greatest extent possible, and the resulting carnage was without precedent in the annals of human civilisation.

Within Germany, Anti-Semitism as a mass phenomenon reared its ugly head. Jews were singled out and blamed for the increasingly problematic supply of foodstuffs (for which the British naval blockade was mainly responsible). There was talk of a ‘Rathenau System’, by which was meant the overdue influence of Jews on the economic and financial life of the Empire, as detailed by industrialist Walther Rathenau (AEG, later Foreign Minister, Feb.-June 1922) in a memorandum dated March 1915. On 11 November 1916, Prussian War Minister Wild von Hohenborn ordered a ‘Counting of the Jews’ (Judenzählung) among the German Army to ascertain how far the Empire’s Jewish communities would contribute to the patriotic burden borne by their fellow-citizens (Klaus Gietinger and Winfried Wolf, Der Seelentröster: Wie Christopher Clark die Deutschen von der Schuld am Ersten Weltkrieg erlöste, Stuttgart, 2017, p. 32).

Throughout the war, the SPD played a crucial, if at first prostrate and subordinate, role. Without the social democratic leadership’s assent, it is quite certain that the war would not have been possible to wage in the form (and how long) it was conducted. The key moment of truth arrived in July 1914 when, contrary to their own anti-war sentiments, the SPD joined the chorus of warmongers. Both the SPD and the union leadership feared martial law, which would have negatively impacted political activism, imposed censorship, and the like.

Yet, the empire’s inner circle—emperor Wilhelm II, the government, and the generals—all knew that this was an ‘all hands on deck’ moment, hence shady backroom dealings between presumed ideological opponents occurred, which resulted in the following de facto trade-off: the SPD would consent to war-funding bills in the Reichstag, and in exchange the government would allow the continued existence of the party. The price to pay was the betrayal of their allegedly long-held anti-war convictions by the SPD leaders, and one is tempted to note that if socialism had a soul, it was promised to the devil in July 1914.

Still, the secular trend of assimilation of the labour movement into the bourgeois system (‘Borg’) commenced well before July 1914. As highlighted by trade union leader Gustav Bauer almost a year earlier in November 1913, the question of ‘the great war’ would be ‘no longer an issue of principle’ rather than ‘a tactical problem: as far as the proletariat is concerned, it needs to be determined whether the war conveys advantages or not, and that this [determination] should guide our behaviour.’ (quoted by Gietinger and Wolf, Der Seelentröster, p. 170.)

It is worth remembering that it was on the occasion of the SPD convention in Mannheim in 1906 when the party leadership moved ‘into’ the bourgeois system by denouncing the possibility of revolutionary change. This momentous change—remember: Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels envisioned the World Revolution to emanate from Germany, which was the most thoroughly industrialised economy and society before 1914—led none other than Max Weber (1864-1920), master analyst of Modernity and its discontents, to say the following:

I would very much liked it to take our German princes with me to the gallery at the Mannheim Party Congress and show them what the assembly was like down below. I had the impression that the Russian socialists, who were sitting there as mere spectators, threw their hands up in horror at the sight of this party, which they regarded as ‘revolutionary’ in the serious sense of the term, which they worshipped as the most powerful cultural achievement in Germany, and as the bearer of a tremendous revolutionary future for the whole world—and in which the ponderous innkeeper’s face, the petty-bourgeois physiognomy, so dominated: There was no talk of revolutionary enthusiasm, and instead a lame, phrase-like nagging, and complaining debate and wailing occurred in place of that Catilinarian energy of enthusiasm [Weber actually wrote Glaube, i.e., faith] which they were accustomed to at their own meetings. (Max Weber, ‘Diskussionsrede bei den Verhandlungen des Vereins für Sozialpolitik in Magdeburg 1907 über Verfassung und Verwaltungsorganisation der Städte’ in Max Weber: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Soziologie und Sozialpolitik, ed. Marianne Weber, Tübingen, 1988, p. 407-12, at 407; my translation and emphases.)

Thus, when push came to shove, the SPD, firmly embedded in the bourgeois system, voted in favour of war financing: an internal vote showed a tally of 96 for, as opposed to 14 MPs who remained true to their convictions. From 4 August 1914 onwards, in every single vote in the Reichstag, the entire parliamentary SPD voted with the government, including Karl Liebknecht (later one of the leading Communist in November 1918) and renowned (fake) anti-war agitator Hugo Haase. There was but one party line: ‘We shall not desert the fatherland in the hour of danger.’ It was easy, then, for Wilhelm II, to state: ‘I know no parties anymore, only Germans!’

It was a tragic farce, for there were tens of thousands of SPD and trade union rank-and-file members who protested; in July 1914, some 750,000 voiced their concerns all over the empire. All these facts have been conveniently omitted from the historical record in favour of the parliamentary SPD siding with the imperial warmongers instead of the working people they claimed to represent.

It was not before December 1914, with the hoped-for quick and easy victory proving elusive, that Karl Liebknecht took the first tentative steps against the harrowing slaughter on the battlefields of Europe. It is beyond doubt that these—courageous—steps contributed to Liebknecht’s eventual murder by members of the Freikorps on 15 January 1919.

Under the strains of their support for the war, the SPD buckled, strained, and eventually split in 1916. Truth be told, what happened is equally telling: the party leadership kicked out all dissenters and anti-war proponents who founded a new party, the Independent Social Democratic Party (independent means unabhängig in German, hence their acronym USPD). They remained a minority, and the SPD remained true to the bourgeois system until the fateful autumn days 1918. Until the bitter end, the SPD was vehemently opposed to anything that endangered the war effort and cooperated closely with the military dictatorship of Field Marshals Ludendorff and Hindenburg. This collaboration frequently resulted in strike leaders being sent to the most dangerous areas of the frontlines (according to von Oertzen, Betriebsräte in der Novemberrevolution, p. 63, n. 2). If there was any doubt about the true colours of the SPD, in particular about their leadership’s acts in autumn 1918, the Great War proved to be their very ow ‘baptism of fire’.

Autumn 1918

Conventional historiography dates the entry into government by the SPD to 9 November 1918, but this is incorrect. It was, in fact, on 3 October 1918 when the imperial government became (somewhat) responsible to parliament. It was on this particular day when SPD leader Philipp Scheidemann and union leader Gustav Bauer were appointed to cabinet positions. It was this revamped, if provisional, government that was tasked by the general staff to ask for an armistice, via US President Woodrow Wilson. In fact, it were the generals—Ludendorff and Hindenburg—who ‘invited’ the SPD to join the government. Here’s Ludendorff who, let’s not mince words about this here either, was (informally) in charge of what amounted to a military dictatorship since 1916, who declared on the occasion:

I have asked His Majesty to now also bring those [political] circles formally into government whose actions are mainly responsible that we managed to get this far.

This turn-of-events would lead Kurt Tucholsky to acidly comment on the matter in the following way:

It is very unfortunate that the SPD calls itself the Social Democratic Party of Germany. If, from 1 August 1914 onwards, it [the SPD] would have called itself ‘Reform-inclined Party’ or ‘Party of the Lesser Evil’ or ‘Here Families May Have Coffee or Something’—many a worker would have had their eyes opened that way. (quoted in Zwecklegenden: Die SPD und das Scheitern der Arbeiterbewegung, eds. Haffner, Hermlin, and Tucholsky, p. 4.)

In other words: it was the SPD leadership that allowed the German war effort to persist until autumn 1918.

Remember, remember, that Treasonous October and November

Most people are unaware of these uncomfortable, if not outright inconvenient, facts. From early 1917 onwards, there were massive rank-and-file-led strikes among industrial workers, in particular in the armaments industries. In January 1918, more than 700,000 workers went on strike. As we shall explore in subsequent instalments, these massive strikes were organised by a Berlin-based small conspiratorial group of revolutionaries. As the military failed to win the war in spring 1918, the following summer months witnessed increasing rates of desertions: within a few weeks, the German Army lost almost one million soldiers while, at the same time, more than 200,000 American soldiers had arrived in France.

As summer gave way to autumn 1918, the situation was increasingly desperate for Wilhelm II, the imperial government, and the generals. In this constellation, we may finally ‘discover’ the true treason: those responsible for the conduct of the war were preparing their escape. As Wilhelm II fled to the Netherlands and Ludendorff went to Sweden, those who remained transferred ‘responsibility’ to the civilians of the bourgeois system, which most notably included the SPD. It was the bourgeois politicians who were left with the thankless task to cover for the failures of the business, financial, and military elites.

In a truly disgusting move, the SPD leadership was really eager to do the bidding of the now-disgraced business, financial, and military elites, as explained by none other than long-time SPD leader Friedrich Ebert.

It is incumbent upon us to throw ourselves into the breach. In doing so, we must see that we can get enough influence to push through our demands, and if it is possible to link them to saving the country, then it is our damned duty and obligation to do so. (quoted by S. Haffner, ‘Der Verrat’, p. 34.)

Poetry and Fiction: A German Tragedy

Herein, in the SPD’s giddy wish to play with the big boys of the business, financial, and military elites, we may finally identify the foundation of the notorious Dolchstoßlegende. Leading SPD politicians like Mr. Ebert were instrumental in pushing the fiction that the German Army ‘remained undefeated in the field’.

The armistice, signed by the new (same as the old) civilian leadership in Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch’s railroad car in Compiègne on 11 November 1918, was asked for by a government that included the SPD. The German generals were the first to abandon the enlisted men and sent a delegation led by Matthias Erzberger to sign the armistice. Erzberger was killed in 1921 by right-win fascistic elements because he did the bidding of the generals.

It is beyond this essay to explore as to why the victorious Allies accepted the motley crew sent to deal with them, but the ‘moderate’ Social Democrats, in cahoots with the long-term supporters of the war from the bourgeois side of the aisle, thereby consciously took ownership of the armistice, the Versailles Treaty, and the disastrous consequences of the Great War.

I shall conclude this first part by arguing that no-one among the German elites ‘sleepwalked’ into the war. This is neither the time nor the place to discuss the infamous war guilt issue (though you are, of course, welcome to do so in the comments below), and I shall close this essay in the following way: mistakes were made, like in every war, but what renders German history so tragic is indeed the utter misrepresentation of what happened, both before July 1914 and in particular after October 1918. In the end, there was gunpowder, treason, and plot, but the betrayal was carried out not only by the German business, financial, and military elites.

This holds particularly true for the self-styled progressive left who joined, rather than denounced, the warmongers and, when push came to shove, sided with the German business, financial, and military elites in their war against the German people.

You do spoil your readers. Being outspoken was to be the burden and duty of the humanities and the social sciences, and look at us now. Rather than doing what you do here, we have instead become the clergy of not only the politically correct, second for second, but the politically expedient career-wise.

Will read more thorough but I'll drop a question here if it's alright:

When studying history in school in Germany and Austria, does the time-line jump from the French Revolution, touching lightly on Napoleon and Marxism, and then mention the wars before settling in and becoming detailed again in the early seventies?

Because swedish history, in school books for the past fifty years basically skips everything but the world wars, during the period 1850 to 1965. Rather than going into detail about recent history, a period where we have lots of material, more time is spent on the neolithic era for comparison.

I ask, and if similar in Austria and Germany wonder if there's a conscious thought behind this, or accident?

Lots of text, so difficult to focus on just one item. But the most enraging part is the lack of morality of anyone in power from 1850 onwards. It is appalling.

"Might makes right" and all that crap I suppose.