Commemorating 1848, German President Lies (by Omission), thus Reinforcing the Decadent Régime

No Legacy Journalist--or Historian--Called Mr. Steinmeier Out, thus Proving Marx Right. If, at Night of Germany I think…

This piece originally appeared in German over at TKP.at; I have, however, elected to slightly revise and extend, as well as added a few bottom lines below.

Fairytales with President Steinmeier on the Anniversary of the 1848 Revolution

And now this has happened. A few months after the abstruse statements of his Austrian counterpart, German Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier (SPD) proudly paraded his ignorance in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt am Main, the location of the historic drafting of the first written constitution in the German lands. Bending facts and omitting necessary contexts, one could counter that there is nothing new under the sun. This proved eventually—and unfortunately so—correct as legacy media once again failed to hold a Federal President to account. A correction.

As the statements by Austrian president Alexander Van der Bellen show, one may have gotten somewhat ‘used’ to grief since the declaration of ‘the pandemic’, but what happened recently in Frankfurt’s Paulskirche is—nothing short of alarming.

Like the 1848ers, Mr. Steinmeier Aimed at Re-Making the World

There the Federal President stood in front of a coterie of invitees, including Nancy Faeser (SPD), currently serving as Minister of the Interior.

In his speech, delivered on 18 May 2023, Mr. Steinmeier stated, among other things (here and in the following, my translation and emphases):

It was a wonderful spring. And the people of 1848 understood that long ago not only meteorologically. It was a political, a social spring, a time of great hopes and expectations…a ‘revolutionary spring’, in Christopher Clark’s words....

The revolution of 1848 and the first German National Assembly here in the Paulskirche—these were unheard-of events for Germany at the time. Hopes ran high, and the willingness to overthrow the old and dare the new had gripped many.

I will spare you a good part of what follows, because in these two paragraphs alone there is so much historical claptrap and revisionist BS that I, as a professor of history, am surprised that the criticism of my colleagues did not follow suit.

Personally, it is completely unclear to me why the reference to the weather is there—because it played at best an indirect role. As ‘even’ Wikipedia notes, ‘the proximate cause of the famine was a potato blight that infected potato crops throughout Europe during the 1840s’. In Ireland alone, the Great Famine, known in Gaelic as Gorta Mor, ‘roughly 1 million people died and more than 1 million fled the country’. Moreover, the potato blight was not restricted to the Emerald Island, which caused ‘an additional 100,000 deaths outside Ireland and influencing much of the unrest in the widespread European Revolutions of 1848’.

Adding insult to injury, as explained by the German-language entry of the same Wikipedia article, continues, the consequences of the Great Famine were ‘greatly exacerbated by the laissez-faire ideology and liberal economic policies of the Whig government under Lord John Russell’.

So much for the partial origins of the ‘beautiful spring’ invoked by Mr. Steinmeier.

A Spectre is Haunting Europe—the Spectre of Fake History

Steinmeier also glossed over the massive economic dislocations that firmly held Europe in its grip during the 1840s. None other than Karl Marx described the depression that had begun in Britain a decade earlier as the ideologically predetermined ‘structural crisis of the bourgeois mode of production’, which was compounded by almost Europe-wide supply shortages. Eric Hobsbawm, writing in The Age of Revolution, repr. London, 1997, p. 307; Italics in the original, bold emphases mine) noted that the Revolutions of 1848

coincided with a social catastrophe: the great depression which swept across the continent from the middle 1840s. Harvests—and especially the potato crop—failed. Entire populations such as those of Ireland, and to a lesser extent Silesia and Flanders, starved.* Food-prices rose. Industrial depression multiplied unemployment, and the masses of the urban labouring poor were deprived of their modest income at the very moment when their cost of living rocketed.

*In the flax-growing districts of Flanders the population dropped by 5 per cent between 1846 and 1848.

As is well known, the Revolutions of 1848 began in Paris in mid-February and spread rapidly ‘to Germany’ and elsewhere as a result of the dissemination of this news. However, anyone who mentions ‘Germany’ in this context without further indication that this country—apart from the spatially diffuse notion of a ‘cultural nation’ (Kulturnation) in the sense of Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814)—did not exist, is engaging in historical revisionism of the crudest kind. In Central Europe, after the Congress of Vienna (1814/15), the so-called German Confederation existed, a loose confederation that included not only Prussia but also the Austrian Empire, as well as some 40 other states.

Anyone who carelessly mentions that kind of ill-defined reference to ‘Germany’ in 2023 (!) is actively narrowing the discursive norms (‘Overton window’) of what can be said and thought in a way that is ahistorical, unscientific and pseudo-populist way.

Now, this is not about the identity of the German people, but anyone who simply mentions the ‘new Germany’ (Neil MacGregor, Germany: Memories of a Nation, London, 2014, p. xxxvii) after "reunification" is engaging in historical malpractice, if not treading on the thin ice of revisionism of the worst kind.

1848 as a ‘Moment of Freedom’, but: For Whom and in Whose Name?

In Karl Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (first edition 1852, 6th ed., 1972, p. 10), one can read the following:

Hegel remarks somewhere that all facts and personages of great importance in world history occur, as it were, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as a tragedy, the second as farce.

Thus fortified, we may now deal once with the lousy farce of Mr. Steinmeier’s presidential speech in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt (my translation and emphases):

But we also know that courageous people with the best of motives set something in motion that was an irreplaceable step on the long road to democracy and freedom in a united Germany. It was the moment, it was the year, when subjects became citizens. When the spirit of freedom was awakened that—at least in the long run—could never be suppressed again.

What Steinmeier is hinting at here is nothing less than the abolition of feudal privileges, above all personal bondage, also known as Leibuntertänigkeit, or subjection). This became known under the catchword of ‘the Liberation of the Peasantry’, or Bauernbefreiung.

As is well known, west of the Rhine, most feudal privileges were abolished in the wake of the French Revolution; east of the Rhine, as well as outside Russia and the Ottoman Empire, it took until 1848/49 for this to be realised. One of the protagonists of this momentous change was Hans Kudlich, whose name adorns a multitude of streets and squares in today’s Germany, Austria, and the Czech Republic; his fame extends as far as the USA, to which Kudlich later emigrated. It is worth pointing out that Mr. Steinmeier, by contrast, did not find it worth his time to mention Kudlich.

Lies of Omissions—As Far As The Eye Can See

With the tone thus set, it is hardly surprising that the rest of the speech is roughly comparable, at least as far as its accuracy is concerned. It is, though, an awe-inspiring moment of gaslighting. Mr. Steinmeier continued:

The men of the National Assembly—they were indeed only men at the time, which is the democratic deficit from today’s point of view—were nevertheless pioneers and trailblazers of ideas that we take for granted today.

These ‘ideas that we take for granted today’—which moved the Vormärz (1815-48) through those very protagonists—included, above all, state-imposed censorship, the political persecution of inconvenient professors (e.g., Heinrich Heine), writers (e.g., Georg Büchner), or ‘activists’ (avant la lettre), most notably Karl Marx, but there were many, many others Germans who met, inevitably, in exile. All of these names are to be understood as pars pro toto.

If one thinks of the current iteration of censorship—pardon: the ‘fight against disinformation’—, one could bring up, for example, the dismissal of Ulrike Guérot or the persecution of Sucharit Bhakdi, among others. Yet, neither censorship nor the political persecution of inconvenient thought-leaders troubled the eternally spotless mind of Mr. Steinmeier, his guests of honour, or members of legacy media who were present at the event. There would certainly be a lot to discuss, yet no such discussion was had.

Speaking of the (temporary) abolition of censorship in 1848, this was one of the more notable achievements of the March Revolution, which, however, did not survive the regrouping of the forces of reaction. I would add that this analogue—antecedent—should certainly be mentioned in times of ‘the pandemic’. As a trained lawyer, it stands to reason that Mr. Steinmeier, a long time ago, came into contact these parts of German legal history, but it is highly questionable whether he ‘still’ remembers these lessons of history after all these years as a politician.

Hence, the only conclusion that is possible is that Mr. Steinmeier’s speech was as poorly prepared by his staffers as it was delivered in a profound disservice to the memory of the ‘March Dead’ (Märzgefallene). It was little more than cheap stunt or agit-prop, as well as a prime example of historical amnesia and self-righteousness. Mr. Steinmeier’s appearance may be useful as teaching material for future generations in the field of Propaganda Studies, but it was certainly a highly embarrassing moment and thoroughly unbecoming of a high state official, in particular given its setting and historical context.

Steinmeier’s Fake Account of Germany’s Long Road West vs. Some Facts

It would tempting, of course, to to dismiss this official celebration as an occasion to feel vicariously embarrassed (note that the German language has this wonderful word Fremdschämen for precisely these moments), but I too—as an Austrian citizen born in Vienna—am affected by this BS. In 1848, by the way, a few other Austrian citizens were present in Frankfurt, and the Habsburg Empire’s Czech citizens were invited, too, but the latter had the grace to declined to continue being ruled by even a constitutionally governed Greater Germany.

[Here follows the one substantial addition to the essay, which comes to us courtesy of one of the user comments below the original German-language essay. Written by the user ‘flatten_the_curve’, several examples of fake history are cited, with another insert by me below; translation and emphases mine.]

As early as 1848 in the Paulskirche, German politicians were agitating for war against Russia:

‘In the East’, the Germans had always succeeded in the course of history in making ‘conquests with the sword [and the] ploughshare’. Germans could and should acknowledge this ‘right to conquer’ (Franz Wigard, ed., Reden für die deutsche Nation, 9 vols., Munich, 1848, here vol. 2, pp. 1145-6).

Another parliamentarian spoke of a ‘holy war’ that would have to be fought out at some point anyway ‘between the culture of the West and the barbarism of the East’ (Günther Wollstein, Das ‘Großdeutschland’ der Paulskirche: Nationale Ziele in der bürgerlichen Revolution 1848/49, Cologne, 1977, p. 303).

Another declared: ‘If war ever came, it would be between Germans and Slavs’ (Wigard, ed., Reden für die deutsche Nation, vol. 4, p. 2779). [line break added]

Heinrich von Gagern [whom Mr. Steinmeier explicitly repeatedly referenced, citing Gagern’s dictum that ‘we have the greatest task to fulfil’ (‘Wir haben die größte Aufgabe zu erfüllen’)] wrote in retrospect about the period of the bourgeois revolution:

‘The war with Russia—for the sake of the Baltic Sea and the Baltic provinces [i.e., dominion over present-day Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania]—for the sake of Poland—for the sake of the Danube and the Oriental conditions…was the most popular matter across all Germany’ (quoted in Veit Valentin, Geschichte der deutschen Revolution von 1848-1849, 2 vols., 1st ed. Berlin, 1930-1931, here repr. Berlin, 1977, vol. 1: p. 544).

[Here follows another brief comment of mine, marked specifically as block quote.]

One would be in a position to ask Mr. Steinmeier as to why he and his staffers chose to deliberately omit these (and many others comparable) statements from the Paulskirche? Alas, legacy media is loath to bring up these and the above-referred passages when commenting on Mr. Steinmeier’s appearance. Parallels are drawn to the present, and mentioned accordingly by, e.g., Matthias Trautsch writing for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung:

[Steinmeier:] ‘Those who mock parliaments today, who constantly speak of the system of Gleichschaltung and dictatorship of opinion, are in fact mocking those who fought for freedom and democracy.’ Already 175 years ago, he said, a counter-movement had emerged together with parliamentarism: ‘A populism that despises institutions and claims the supposedly true will of the people for itself.’ The idea of the nation democratised the state, but also gave rise to exclusionary nationalism.’

As the above-related quotes show, these sentiments were perhaps ‘populist’ in the sense of this jingoism being espoused by ‘Germany’s leading bourgeois parliamentarians. The conclusion of Mr. Trautsch is, nicely put, historically inaccurate, to say the least.

Bottom Lines, or: Speaking of ‘Freedom’ in ‘1848’

The abolition of subjection was, according to the pertinent study by political economist Georg Friedrich Knapp (1842-1926) something whose origin can clearly be located before 1848.

In Knapp’s magisterial treatise, entitled Die Bauernbefreiung und der Ursprung der Landarbeiter (2 vols., Leipzig 1887), one could find out ‘more’, albeit ‘only’ if one reads German as neither this work nor his subsequent collection of relevant essays, published under the title Die Landarbeiter in Knechtschaft und Freiheit: Vier Vorträge (Leipzig, 1891), were translated. If you are interested in the topic, I recommend Markus Cerman’s well-composed synthesis, entitled Villagers and Lords in Eastern Europe, 1300-1800 (London, 2012), with a good comment on this historiography in Ch. 1.

In Die Bauerbefreiung, Knapp wrote (vol. 1, pp. iii-iv; my translation and emphases):

The history of the liberation of the peasantry is the history of the social question of the 18th century. The social question of the 19th century is less related to the peasants than to the workers, in particular with rural workers…

Thus, we are not considering agriculture but rather the people working in this industry, the rural constitution, the social relations of the various classes, and the positioning of the state in-between. In researching the liberation of the peasantry and the origins of the rural workers, we are investigating the socio-political history of the rural population. [The latter constituted the overwhelming majority of people around the mid-19th century; in the Habsburg Empire in 1851, for example, only 2% of the population lived in Vienna, Budapest, and Prague; this was the same time when, for the first time in history, the urban population of the UK, standing at 51%, exceeded its rural counterpart]

Mr Steinmeier also omitted these aspects. Why?

Note, as an aside, that Knapp today is mainly remembered for his treatise on monetary systems. First published under the title Staatliche Theorie des Geldes (Leipzig, 1905), an abridged version appeared as The State Theory of Money, trans. H. Lucas and J. Bonar (London, 1924); his considerations informed the emergence of Monetary Theory and what eventually became known as ‘Keynesianism’.

Epilogue: Three Social Questions

Industrialisation, the emergence of mass societies based on wage labour and the tensions and dislocations associated with it are ‘the social question of the 19th century’.

Its (partial) ‘solution’, obviously, occurred in the third quarter of the 20th century—through the gradual introduction and expansion of the social security and welfare state, whose roots, however, hark back to the 19th century.

These achievements of the 20th century have given the Western nations, among other things, a drastic increase in life expectancy, prosperity, and led to a population explosion worldwide.

These are, I would argue in all brevity, the core aspects of the ‘social question of the 20th century’, but: what about its solution?

Most humans are, according to WEF apologist Yuval Harari, ‘useless eaters’:

There is not a shred of nuisance or novelty in Harari’s ‘ideas’, which is hardly surprising given that he is bought and paid for by the bigwigs and eugenicists around Bill Gates, Nobel Peace Prize winner (war criminal) Henry Kissinger, and their ilk.

What, then, do you think is their vision for ‘resolution of the social question of the 20th century’?

Mr. Steinmeier has delivered something in the Paulskirche, even though he did not to anything related to the sovereign people, but for his superiors.

What happened is revelatory in only one sense, for Mr. Steinmeier’s speech dragged Germany’s ‘elite’ out into the limelight. And there, for everyone to see, were people who can be described as decadent, self-righteous, and wearing ideological blinders. This is how one can—must—describe the current ‘moment’ and the ‘elites’ of what is commonly, and historically inaccurately, called ‘Germany’.

An almost perfect ‘lumpen farce’, as related by Marx (albeit writing about Louis Bonaparte’s coup d’état in 1852).

Grotesque and disgusting, but it remains an accurate description.

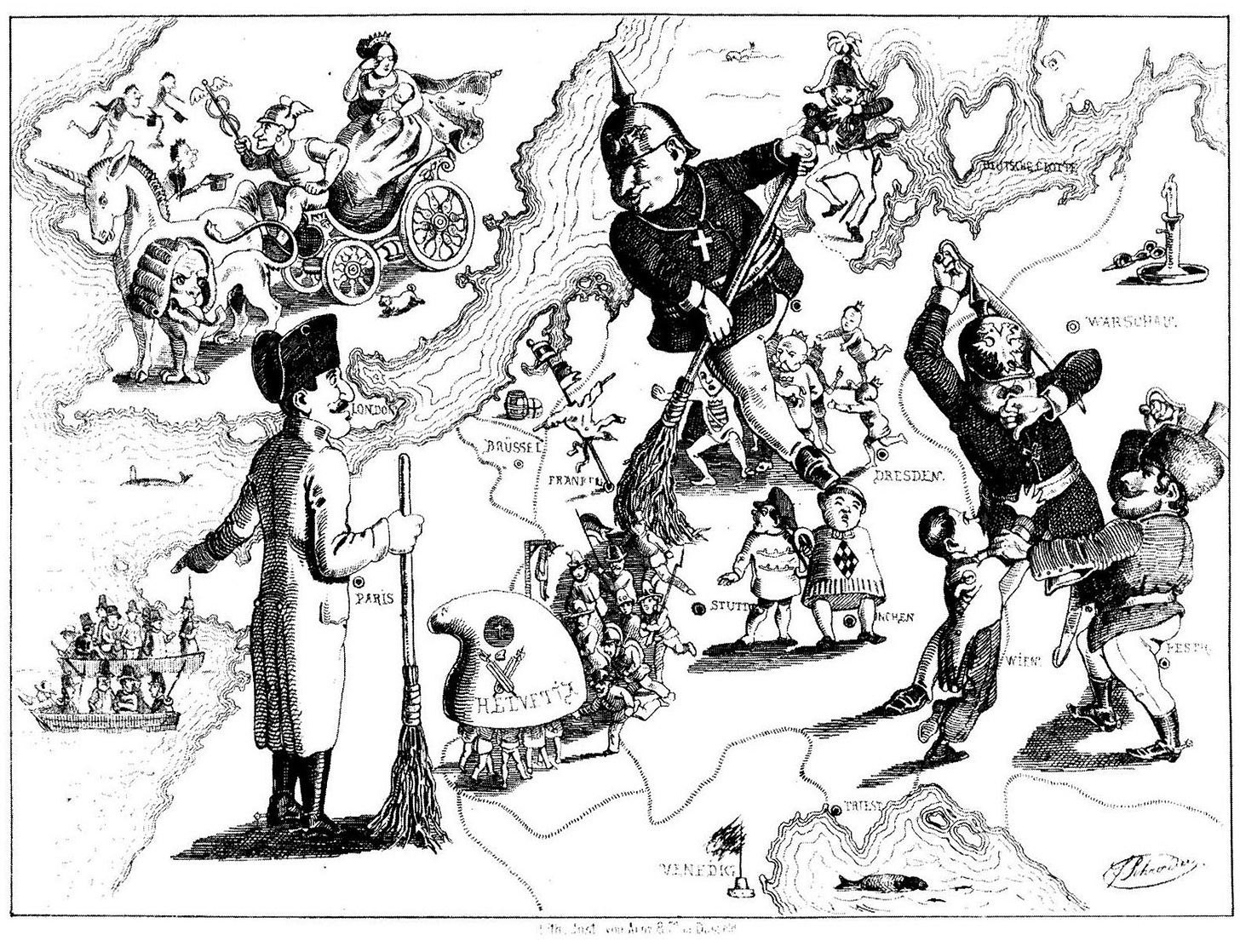

I like the leering jeering dane dancing in the upper middle of the picture. (Or is it supposed to be Schleswig-Holstein and their brief attempt at becoming a state in their own right?)

Thanks Epimetheus, and interesting read.