AI Rules for We, the People, as Digital Ethicists (sic) Propose 'Limits to Nonsense'

Courtesy of ze Experts™, we get a glimpse of the shape of things to come with respect to limitations of AI use for regular people vs. all the good stuff the gov't is going to deliver using AI

We’ll stay on the topic of ‘AI™’ for a moment longer, if only because now that it has seemingly come of age and quite ubiquitous, first ‘warning signs’ are appearing.

You see, ‘many AI researchers’ are now warning of its ‘environmental impact’, which means—we, the taxpaying public, paid for its development and implementation in, say, government, yet it’s actually bad for ‘ze planet’ (read with Klaus Schwab’s voice).

Of course, there is but one ‘solution™’ here: gov’t regulation, upper limits as to what any person shall be permitted to do with ‘AI™’, and a heavier hand of the public-private behemoth meddling in our daily lives.

Oh, lest I forget: if Elon Musk and his ilk will get to play DOGE™ in the US, they’ll certainly claim to be the world’s first to ‘use AI’ in governance, but you could easily tell that particular attempt at gaslighting:

For what follows, please enjoy (sic) my translation, emphases, and [snark].

Asking ChatGPT Consumes [a lot of] Water: ‘There should be an upper limit for nonsense questions’

Artificial intelligence consumes large amounts of energy and water. AI is not a toy, according to several AI researchers.

By Annvor Seim Vestrheim and Julie Helene Günther, NRK, 26 Dec. 2024 [source]

You ask ChatGPT what you want for dinner and ask it to customise your recipe with more ingredients. But ChatGPT is thirsty.

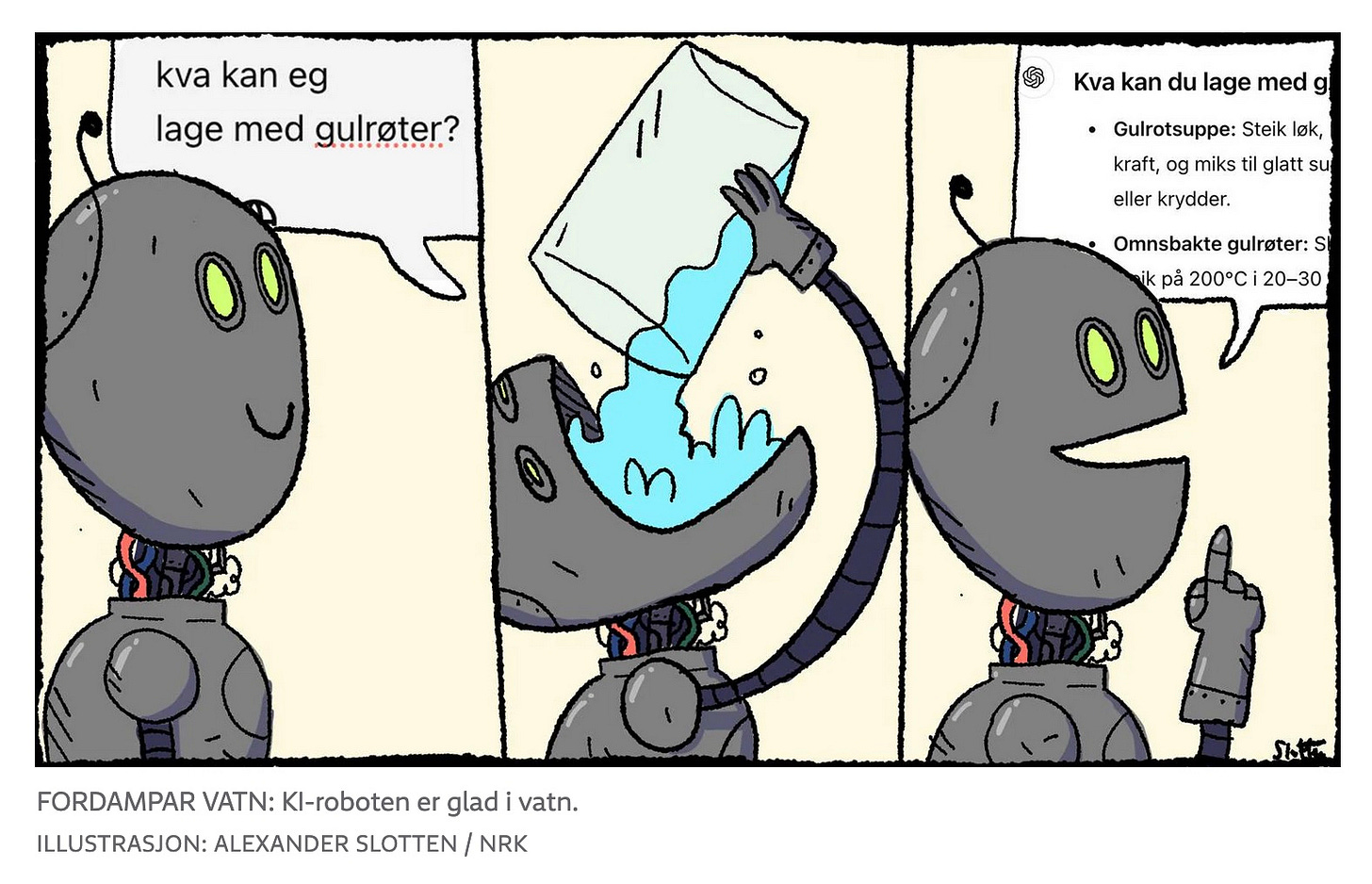

[this comic accompanies the piece; frame 1] ‘what food can I prepare with carrots?’ [frame 2: subtitle ‘AI chatbot loves water’; with frame 3 indicating recipes]

While you’re trying to figure out what to do with the carrots at the bottom of the fridge [easy, we always make the horses happy with them], the AI chatbot needs water to answer your questions [I knew about the horsey stuff w/o ‘AI’].

While AI chatbots are tools that can find solutions to the climate crisis, they also contribute to making it worse [talk about the ‘cure’ being worse than the disease, eh?]

‘There’s something about realising that the time of corporate games is over, that this is not a tool for play’, says Leonora Bergsjø, who researches digital ethics [here’s her faculty profile at the U of Agder in southern Norway; she does ‘digital ethics’, which is about as real as ‘bio/medical ethics’ (esp. in the context of the Covid ‘pandemic™’); note that she is actually an associate professor whose primary employment is with the Department of Natural Sciences, Practical-Aesthetic, Social and Religious Studies at Østfold University College where she ‘teaches at primary and lower secondary teacher education and kindergarten teacher education…in digital judgement, ethics, religion and worldviews’—in other words: she’s not a data scientist but someone with a degree in pedagogy expressing profoundly statist views].

Thirsty Data Centres Devour Water

It is generative [sic, and note this is perhaps the biggest trick (scam) played here: ‘AI’ as it currently exists is a glorified ‘official sources’ plus Wikipedia blender, which means it’s everything but generative] artificial intelligence that makes it possible for you to get images and text in a conversation [sic] with language models, such as ChatGPT [there is no ‘conversation’ to be had with a language model however large it may be; these LLMs merely regurgitate whatever they find where they look; Grok, for instance, often notes ‘25 websites’ and x (no pun intended) ‘number of profiles’ used for drawing up an ‘answer’; put differently, if I’d wanted to gaslight you with ‘AI™’, I’d build ‘preferential sources’ into that thing and voilà, ‘AI will set us free’].

To find the next word in a sentence, a large language model has to make a lot of calculations [see what I mean? It’s an entirely probabilistic activity that has nothing to do with the generation of a thought, word, or idea on its own].

A series of five to 50 questions for ChatGPT can evaporate half a litre of water.

This is according to American AI researcher Shaolei Ren to NRK [unlike the first ‘expert™’ cited, he’s actually an associate professor in electrical and data engineering with a degree in engineering from UCLA who currently works at the UC at Riverside]

His estimate includes indirect consumption of water that the companies do not measure, such as the cooling of the power plants that supply the data centres with electricity [go ahead, it’s a pre-print, but note that the underlying idea—of ‘indirect’ costs vs. benefits—is quite disingenuous: it also renders you guilty (by association) if you don’t use/agree with, e.g., gov’t using AI/or the like: it’s a cheap trick to make everyone liable for the actions of a few—you see, you may have read my recent posting (using Grok), and even if you didn’t use ‘AI™’ yourself, I did—and by association, you’re on the hook].

The amount of water that evaporates depends on cooling, climate [whatever that means here], and energy source. For example, a data centre in Arizona uses more water to cool down servers than one in Norway, under otherwise similar conditions, according to Ren [what a brilliant observation; where is the Nobel prize committee when you need it?], adding:

But we don’t have a clear picture of AI’s actual water footprint due to a lack of transparency.

Ren has researched how much water the language model needs to answer the questions it receives, and how AI affects the climate:

Water scarcity is perhaps the most direct consequence of climate change. At the same time, the rapidly growing demand for AI is fuelling global water consumption.

Does Not Have a Complete Overview

Like Ren, Sintef [a non-governmental R&D organisation based in Trondheim, Norway] researcher Signe Riemer-Sørensen [profile; she holds a doctorate in astrophysics from the U of Copenhagen’s Niels Bohr Centre and, unlike the first ‘expert™’ cited by NRK, actually knows a thing or two about, you know, physics and engineering] emphasises that it is difficult to know how much water the AI services actually use.

She believes there is little transparency in the industry when it comes to the use of water.

But we do know something.

According to the company’s sustainability report, Microsoft’s water consumption increased by 34% in 2022 from the previous year, according to the AP [full disclosure: I work at a public university in Norway, and this year, our IT department has fully implemented their ‘AI™’ bot (it’s called ‘Autopilot’ and, no, it doesn’t look like that annoying paperclip of old), which at least I can tell you I’ve never used, nor am I planning to do so]

This corresponds to an amount of water equivalent to more than 2,500 Olympic swimming pools.

The main reason was the collaboration with OpenAI, which is behind the language model ChatGPT. Reuters reported in August that ChatGPT has around 200 million active users per week.

OpenAI has not responded to NRK’s questions about how much water they used in 2023 [why am I not surprised at this point?].

Limits to ‘Nonsense’

AI tools can be useful and make tasks more efficient. But many people also use the technology to create songs or funny pictures and videos [ah, you proles, are you doing creative, non-approved™ stuff with these wonderful toys that our saviours have devised to bring us to Mars? How dare you].

But a query to GPT chat requires about five times as much energy as a regular Google search, according to Carbon Credits [sadly, NRK doesn’t provide a link to the source, which I do: long story short—Big Tech is greenwashing its emissions, hence a scam, because what these megacorporations are doing is ‘offsetting’ their emissions by acquiring what is called ‘unbundled RECs’, or ‘renewable energy certificates’, which are essentially a booming derivative ‘market™’ (scam), which is likely to implode before too long, leaving behind, as always when bubbles burst, Big Business much bigger and many small investors in the lurch].

Riemer-Sørensen believes that there should be an upper limit for how much ‘nonsense’ the energy from a data centre should be used for [note that despite her employer being an ‘independent’ R&D organisation Sintef, she also calls for more (gov’t, but presumably also corporate) regulation of consumer behaviour]:

Regulated data centres will make it possible to use computing power on measures that benefit the climate, rather than an artificial need for everyone to generate their own cat video.

Riemer-Sørensen is supported by Associate Professor at Østfold University College Leonora Bergsjø, who researches AI and digital ethics [we met her at the beginning of the article, but since there were a bunch of people mentioned in-between, most readers will have forgotten that Ms. Bergsjø was introduced without affiliation—and here NRK casually omits that she holds a Ph.D. in education/pedagogy]:

‘People need to be aware of the environmental consequences of using the technology’, says Bergsjø, adding that companies should create their own guidelines for the use of AI [ah, of course, and guess who will enforce compliance with these internal guidelines? And that’s even before we consider the role of gov’t and/or regulatory agencies as in—should gov’t enforce internal guidelines? The answer for the climate commies is, and always has been, ‘of course, it’s for the greater good’].

It’s not a prudent use, especially of AI-generated images. So raising awareness is simply the first step, and that’s the hardest part. [Ignacio de Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order, allegedly* said ‘Give me the child for the first seven years and I will give you the man’, and now it does make sense that Ms. Bergsjø—who teaches digital ethics to kindergarten and primary school teacher-students—is given such a prominent place in this piece; *note that the origin of the quote is disputed and that it may been ‘attributed to him (perhaps mischievously) by Voltaire’, as even Wikiquote informs us]

I’ve been toying with the idea of a new kind of aeroplane shame, AI shame [orig. flyskam in the former context and KI skam in the latter, i.e., the conscious shaming of those who use airplanes; it’s particularly pernicious when someone like Ms. Bergsjø ‘plays’ with the idea of ‘shaming’ kindergarten and primary school-age children].

Government is Investing in More AI

Before the end of 2025, 80% of the public sector will use artificial intelligence [so the Norwegian gov’t will ‘harm the climate’ by doing so].

The Ministry of Digitisation and Public Administration told NRK that they are not aware of any specific figures on how much of the AI use is linked to Norwegian or foreign data centres [it’s the same scam as public officialdom was doing during the Covid ‘pandemic™’, by the way: we don’t know nuthin’ ‘bout any adverse events].

Norwegian governments can set requirements for data centres physically located in Norway, but not data centres located outside our borders.

According to the ministry, it is up to the government of the country where the data centre is located when it comes to sustainability requirements:

In Norway, the government is focusing on building green and sustainable data centres [good for the companies feeding on the public trough], ‘because AI is generally energy-intensive, energy and resource efficiency in the infrastructure for AI plays an important role’, writes Minister of Digitisation Karianne Tung in an email to NRK [I’d love to know the carbon footprint of such emails].

According to Tung, climate change, sustainable digitalisation, and the use of AI are on the international agenda and are being followed up in Norway’s cooperation with the other Nordic countries, the EU, and the OECD [translation: the EU and the OECD will propose—more ‘gov’t regulation’ of the ‘online behaviour’ of us pesky proles].

In spring 2025, the minister will present the principles for green and sustainable AI in the data centre strategy [which is what I’ll be ‘looking forward to’ (not), and we’ll revisit this BS then].

So it is still difficult to know anything about the climate consequences of the Norwegian AI programme [see, if you don’t know anything, it’s hard to comment on it].

[this poll accompanies the NRK piece] ‘Do you consider the environment when you use AI?’—‘No, I don’t care: 21%’—‘Yes, I always think twice before I use AI: 27%’—‘I didn’t know AI consumes that much water: 52%’, with 8,638 votes in total (excl. mine) on 30 Dec. 2024 around 6:30 a.m. local time.

The UN is Concerned About Water Use

Although Norway is investing in renewable energy and sustainable data centres in this country, this does not mean that the AI models used in Norway are sustainable, according to AI researcher Shaolei Ren.

Shaolei Ren believes that Norwegians should be aware that the use of AI here in Norway can have consequences beyond our national borders, and that Norway has a responsibility to the outside world [what happens in Norway doesn’t stay in Norway]:

When it comes to ethical AI, smaller countries can take into account the environmental consequences of AI in other countries outside their own borders.

For example, they can demand that AI models are developed in line with ethical principles and in an environmentally sustainable way [and how would that be possible? I mean, if AI is unsustainable, we better ban it outright, eh? But, epimetheus, doing so would negatively impact Big Tech! And here, in a nutshell, we find out what Mr. Ren is saying: rules for thee, but not for me].

The UN also expresses concern about the unquenchable thirst for AI in the World Water Development Report for 2024.

Among other things, the report states that all the water used for AI should be taken into account when allocating water resources, especially in areas where water is scarce [like, in the Arizona desert you mean?] or at risk of becoming scarce [so, the 64,000 US$ question is, and always has been, who’s doin’ that allocatin’?]

Google is still planning to build data centres in areas of South America that have been hit hard by extreme drought [kinda tells you, by the way, that ‘the internet’ is also quite location-dependent and not merely a ‘cloudy’ aspect].

In any case, the demand for KI will only increase in the years to come.

‘Global demand will account for 4.2 to 6.6 billion cubic metres of water consumption in 2027,’ explains AI researcher Ren [for comparisons, I queried Grok once more and learned that this is roughly equivalent to the Mediterranean Sea (approx. 3,75 billion cubic kilometres, which is 3.75 quadrillion cubic metres of water [as reader

pointed out: thank you, my friend—I merely copied that info from Grok, which kinda proves my point and that I’m human, i.e., fallible]) plus the Black Sea (approx. 547,000 cubic metres of water) combined].That’s more than four times the annual water consumption of Denmark.

Bottom Lines

This piece is long enough already, so I’ll delimit myself to a few notes:

First up, further reading incl. this quite good piece in Forbes, which provides a helpful guide through Shaolei Ren’s pre-print paper. For the latter’s abstract, read on:

The growing carbon footprint of artificial intelligence (AI) models, especially large ones such as GPT-3 [we’re note well beyond that level], has been undergoing public scrutiny. Unfortunately, however, the equally important and enormous water (withdrawal and consumption) footprint of AI models has remained under the radar. For example, training GPT-3 in Microsoft’s state-of-the-art U.S. data centers can directly evaporate 700,000 liters of clean freshwater, but such information has been kept a secret. More critically, the global AI demand may be accountable for 4.2 – 6.6 billion cubic meters of water withdrawal in 2027, which is more than the total annual water withdrawal of 4–6 Denmark or half of the United Kingdom. This is very concerning, as freshwater scarcity has become one of the most pressing challenges shared by all of us in the wake of the rapidly growing population, depleting water resources, and aging water infrastructures. To respond to the global water challenges, AI models can, and also must, take social responsibility and lead by example by addressing their own water footprint. In this paper, we provide a principled methodology to estimate the water footprint of AI models, and also discuss the unique spatial-temporal diversities of AI models’ runtime water efficiency. Finally, we highlight the necessity of holistically addressing water footprint along with carbon footprint to enable truly sustainable AI.

Translated from the academese: everytime ‘social responsibility’ is invoked, esp. if done in an allegedly ‘holistic’ way, what is meant is: more top-down, centralised command and control.

This will be achieved, of course, not through the rather crude five-year plans of Soviet vintage, but via more ‘elegant’ solutions pioneered by ‘innovative stakeholders’ and rolled out via public-private partnerships approved by Davos.

The most telling part—and the last segment I’ll cite here—follows at the end of the paper:

“Follow the Sun” or “Unfollow the Sun”

To cut the carbon footprint, it is preferable to “follow the sun” when solar energy is more abundant. Nonetheless, to cut the water footprint, it may be more appealing to “unfollow the sun” to avoid high-temperature hours of a day when WUE is high. This conflict can be shown in Figure 2(a) [omitted here], where we see that the scope-2 water consumption intensity factor and carbon emission rate are not well aligned: minimizing one footprint might increase the other footprint. Thus, to judiciously achieve a balance between “follow the sun” for carbon efficiency and “unfollow the sun” for water efficiency, we need to reconcile the potential water-carbon conflicts by using new and holistic approaches.

Needless to say, there is not a single such ‘new and holistic’ approach proposed, that is, if you exclude nuggets of wisdom, such as this one:

By exploiting spatial-temporal diversity of water efficiency, we can dynamically schedule AI model training and inference to cut the water footprint.

It’s a vainglorious way of saying: train AI models when it’s dirt cheap to do so (at night), and preferably locate data centres where there’s a lot of water and ‘green™’ electricity.

The (unintentionally) funniest part is the final sentence of the appendix, though, which gives away the essence of the paper:

Like the prediction of global AI energy consumption in 2027 [30], the prediction of water withdrawal and consumption for global AI in 2027 should only be interpreted as a rough first-order estimate subject to future uncertainties.

Now you see the piss-poor ‘reporting™’ for what it is: ‘journos™’ take an unsubstantiated claim from a pre-print that comes with many disclaimers and such, and blow it out of proportion.

Remember that these ‘journos™’ also open their piece quoting from Ms. Bergsjø who holds a Ph.D. in education and typically teaches kindergarten and primary school teacher-students.

It is her pro-gov’t and pro-regulation of thought input that frames the above piece, and this should give us all pause. Ms. Bergsjø teaches (sic) ‘digital ethics’, which means that the teacher-students will introduce corresponding themes to kindergarten and primary school-age kids.

They’re indoctrinating the children in their doom cult and preparing them for a career of activism in the mould of Gretha Thunberg.

This won’t end well. Heck, it’s already bad enough.

It is bad enough the taxpayer is on the hook for public utilities and the running of the grid, which is used at ‘market rates’ by Big Tech.

Now we, the people get to continue paying for electricity generation and infrastructure upkeep, but Big Tech will be permitted their use without we, the people will get our access limited.

Hence, this shit-show will turn for ‘bad enough already’ to worse before too long.

If for the sake of argument we grant that lots of water gets "used up", the logical conclusion is to put the data centers in Norway, they have lots of water, cheap electricity and cool air.

I don't get the principle of "water evaporation in AI use".

Without having read - nor ingested the "Ren paper" into an AI model for "prole consumption of scientific research" - how does the use of AI "evaporate" water?

Are these H100 / Blackwells running that hot that they are not merely "cooled" by a refreshing stream of water? No? Water is poured directly into a "hot like lava" processor system, where a good 30% immediately "evaporates" into clouds?

Which of course also would mean if you understand your nature science "cycle of water" that it would benefit someone or somewhere in the form of future rainfall?

I have to ask ChatGPT how this works, since I am too lazy to remember my own nature scientific upbringing - nah, I'll do it later after quaffing some cool, refreshing water (in the form of beer).